The History of Florida (13 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

cal

Review

8 (1942):533–61.

Wharton, Charles H.

The

Natural

Environments

of

Georgia

. Atlanta: Georgia Department of Natural Resources, 1977.

4

Settlement and Survival

Eugene Lyon

Despite the poor opinion of Florida held at the Spanish Court and the belief

that the French were equal y uninterested in settling there, the situation was

about to change dramatical y. A brief look at France in this period helps to

explain why.

After the middle of the sixteenth century, France was rent by internal dis-

sension between its Crown and groups of powerful nobles. Those conflicts,

which had come to a head in 1560, were worsened by religious differences

between Catholics and Protestants that often erupted into violence. The

proof

intervention of other nations such as Spain in these internal wars further

destabilized France. Queen Catherine de Medicis, acting as regent for her

minor sons, Francis and Charles, temporized with the various factions and

married her daughter to King Felipe (Philip) II of Spain, but she was also

influenced by Gaspard de Coligny,

seigneur

of Châtillon, a Protestant noble

and admiral of France.

Despite internal troubles, France continued its Atlantic policy. When

the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559) ended the last war with Spain, the

parties had not agreed upon the vital issue of the right of nations to settle

in the Americas, leaving the matter in an ambiguous state. While Spain

insisted that the papal donations gave her exclusive rights to North Amer-

ica, the French maintained that unsettled areas were free for anyone to sail

to and colonize. Thus, beginning in 1562, with the support of the French

Crown, Coligny dispatched three royal expeditions to what France cal ed

Nouvelle France (New France), on the southeast coast of what is now the

United States. Like Coligny himself, many of the leaders and mariners on

those voyages were Calvinist Protestants from the ports of Normandy and

Brittany.

· 55 ·

56 · Eugene Lyon

An able captain, Jean Ribaut, commanded the first expedition, which

made landfall near the present site of St. Augustine in the spring of 1562 and

erected a marble column bearing the French arms near the mouth of the St.

Johns, which he called the River May. Proceeding northward, he discovered

Port Royal harbor and planted a colony there, guarded by a fortification

cal ed Charlesfort. But when he returned to Europe, Ribaut was arrested

and detained in England; that and continuing disturbances in France pre-

vented the sending of reinforcements to Port Royal until April 1564. That

year proved to be one of heavy European traffic to and from Florida.

The Spaniards had learned belatedly of Ribaut’s settlement the year be-

fore, and Philip II licensed Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón the younger to settle

Florida but he never sailed. Then the Cuban governor sent an expedition

to probe the French base. Arriving at Port Royal in late May, the Spaniards

found that the discouraged Frenchmen had already deserted the place, leav-

ing behind among the Indians one young man, Guil aume Rouffi. They re-

turned to Havana, bearing Rouffi and the news of the failed French colony.

Meanwhile, on 22 April 1564, René de Laudonnière sailed from LeHavre

with a full-fledged expedition of colonization, and somehow his departure

escaped immediate Spanish attention. The French ships were laden with

livestock, supplies, and tools for husbandry and Indian trade. There were

proof

artisans, women and children, and Protestant nobles from France and Ger-

many. Once in Florida, the Frenchmen did not settle again at Port Royal;

instead, they built Fort Caroline inside the mouth of the St. Johns, overlook-

ing the river. At first, the colony prospered as Laudonnière set out to explore

the interior of New France. He established general y good relations with the

Native Americans in the nearby Timucua and Mocama groupings. Believ-

ing that the great river was the highway to the exploitation of peninsular

Florida, he dispatched an expedition upriver, perhaps as far as Lake George.

Guil aume Brouhart, one of those who made the river voyage, reported that

the Indians there were powerful warriors and skilled bowmen who lived in

a fruitful land of maize and grapevines, rich in nuts, fruits, deer, and small

game.

Supplies soon ran short in Fort Caroline, and not enough food could

be obtained from the natives. A series of mutinies and desertions began.

Eleven men fled in a small craft, and then in December 1564, seventy men

captured Laudonnière and forced him to authorize their departure in two

vessels. Al the deserters headed for the booty they hoped to gain in the

Spanish Caribbean. Instead, their adventure led to the capture of some of

their number and the unmasking of the French colony. After corsairing and

Settlement and Survival · 57

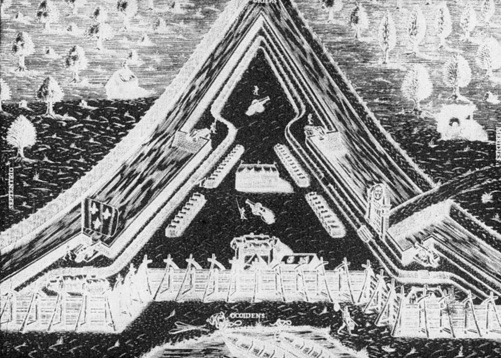

The French Fort Caroline was founded in 1564 by René Goulaine de Laudonnière a

short distance inside the mouth of the St. Johns River, which the French called “Rivière

de Mai.” This drawing, by Jacques le Moyne de Morgues, who accompanied Laudon-

nière, was published by Théodor de Bry in 1591. Laudonnière was relieved of command

proof

by Jean Ribaut in 1565. The fort was captured by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés in the same

year and renamed San Mateo.

raiding in Cuba and Hispaniola, two groups of the Frenchmen were cap-

tured by the Spaniards; only one small ship returned to Fort Caroline. But

word had now been sent to Madrid, and Philip II was made aware of the

French settlement.

In the meantime, the French Crown had prepared to send Jean Ribaut to

reinforce Fort Caroline with a sizable fleet. The report of a skilled Spanish

spy, Dr. Gabriel de Enveja, gave Philip II a full account of the ships, soldiers,

and supplies being readied in Dieppe for the Florida voyage. More than 500

arquebusiers and their munitions, together with many dismounted bronze

cannons, were loaded aboard. Ribaut himself went armed with royal decrees

making him “captain general and viceroy” of New France.

But by this time, Philip II had already granted a contract to a new Florida

adelantado, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés. Even though the news of Laudon-

nière’s fort impelled the Spanish king to add royal aid to Menéndez’s effort,

private motivations in the Florida conquest remained significant. Like other

would-be Spanish conquerors, Pedro Menéndez had contracted with his

58 · Eugene Lyon

king and had been promised the offices and titles of governor, captain gen-

eral, and adelantado. Under his agreement, Menéndez was obliged to found

two cities and was charged with seeing that the natives were converted to

the Roman Catholic faith. If successful in his enterprise, Menéndez would

receive a large land grant and the title of marquis to go with it. His jurisdic-

tion was immense, extending from Newfoundland to the Florida Keys and,

after 1573, westward to México.

In the days of Emperor Charles V, Menéndez had come to royal attention

for his daring deeds in the Bay of Biscay against French corsairs. Thereaf-

ter, he advanced himself in royal favor while he fought Spain’s enemies at

sea and on land. The young seaman became renowned for his prompt and

decisive actions. For his services to Mary Tudor and young King Philip, the

Asturian was awarded a habit in the prestigious Order of Santiago.

Menéndez’s exploits and his influence with the Crown aroused the jeal-

ousy of the Seville merchants and the associated Crown agency, the Casa

de Contratacion (House of Trade). He was jailed by Casa officials in 1563

for alleged smuggling but succeeded in having his case transferred to court.

Thereafter, when the urgencies of the Florida matter came to the Crown’s at-

tention early in 1565, Menéndez was available to serve as adelantado. Before

he learned of the existence of Fort Caroline, Menéndez disclosed his interest

proof

in the fabled Northwest Passage and the route to the riches of the Orient,

when he told the king of his geographic and strategic beliefs about Florida:

If the French or English should come to settle Florida . . . it would be

the greatest inconvenience, as much for the mines and territories of

New Spain as for the navigation and trade of China and Molucca, if

that arm of the sea goes to the South Sea, as is certain. . . . By being

masters of Newfoundland. . . . Your Majesty may proceed to master

that land. . . . It is such a great land and [situated] at such a good junc-

ture, that if some other nations go to settle it . . . it will afterwards be

most difficult to take and master it.

And they must go directly to Cape Santa Elena, and, with fast ships

discover all the bays, rivers, sounds and shallows on the route to New-

foundland. And to provide settlers, in the largest number possible, for

two or three towns in the places which seem best . . . and after seeking

out the best ports, having first explored inland for four or five leagues,

to see that it might have a good disposition of land for farming and

livestock-raising. And each town would have its fort to defend against

the Indians if they should come upon them, or against other nations.1

Settlement and Survival · 59

Menéndez expected the Florida enterprise to prove profitable to himself and

to the Crown. He anticipated the development of agriculture, stock-raising,

fisheries, and forest resources for naval stores and shipbuilding. Menéndez

also hoped to profit from the ships’ licenses granted to him. He planned to

utilize waterways that he believed connected with the mines of New Spain

and the Pacific and those he thought crossed Florida from the Atlantic to

the Gulf.

In his Florida venture, the kinship alliance that supported the adelantado

was made up of seventeen families from the north of Spain, closely tied

by blood and marriage. Members of this coterie pledged their persons and

their fortunes to sustain their leader’s efforts, and they hoped to acquire

town and country lands and civil and military offices in Florida. These part-

ners in Menéndez’s enterprise thus shared his vision of enlarged estate and

advanced standing before their sovereign. The existence of this familial ter-

ritorial elite explains much of the dynamism of the Florida enterprise; the

adelantado was loyal y if not always ably served by his lieutenants and other

officials, who held such close connection with him.

At the end of June 1565, Menéndez sailed for Florida with ten ships and

more than a thousand men. Other ships departed from the north of Spain,

and Menéndez was to receive added support from Santo Domingo. His voy-

proof

age was beset with storms; several ships were lost before he reached Puerto

Rico. He decided to strike out for Florida with the reduced forces he had at

hand.

The adelantado arrived at Cape Canaveral in late August 1565. He knew

that Jean Ribaut had sailed from Dieppe at the end of May with reinforce-

ments for Laudonnière. The Spaniards had pressed their voyage, hoping

to arrive at Fort Caroline before Ribaut. In the event, Menéndez found the

French fleet already anchored off the St. Johns bar. After a short but sharp

battle, the French put out to sea and Menéndez sailed south to found St.

Augustine.

To affirm his king’s title to North America, Menéndez took formal pos-

session of all Florida when he landed at St. Augustine on 8 September 1565,

official y placing the land and its peoples under Philip II’s authority. This

action authorized Menéndez to dispense lands to his followers and to make

treaties with the natives. The adelantado built his first fort in Florida around

a longhouse given him by Seloy, a local leader of the numerous and power-

ful Eastern Timucua people.

After Ribaut failed in an attack on the new Spanish colony, a storm struck

the French fleet. Sensing that Fort Caroline was weakly defended and that