The History of Florida (17 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

Hudson, Charles.

The

Juan

Pardo

Expeditions:

Explorations

of

the

Carolinas

and

Tennessee,

1566–1568.

Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990.

Lyon, Eugene. “The Control Structure of Spanish Florida, 1580.” manuscript, Center for

Historic Research, Flagler College, 1977.

———. “Cultural Brokers in Sixteenth-Century Spanish Florida.” Symposium, “The Prov-

inces of Florida: Defining a Spanish-Indian Society in Colonial North America.” Johns

Hopkins University, 1987.

———

.

The

Enterprise

of

Florida:

Pedro

Menéndez

de

Avilés

and

the

Spanish

Conquest

of

1565–1568.

Gainesville: University Presses of Florida, 1976.

———. “La Visita de 1576 y la Transformacion del Gobierno en la Florida. Espanola.”

La

Influencia

de

España

en

el

Caribe,

la

Florida

y

la

Luisiana.

Madrid: Ministero de Cultura, 1983.

———

.

Pedro

Menéndez

de

Avilés:

A

Sourcebook.

Hamden, Conn.: Spanish Borderland Sourcebooks, Garland Publishing Company, 1994.

Settlement and Survival · 75

———. “The Revolt of 1576 at Santa Elena: A Failure of Indian Policy.” Paper. American

Historical Association, Washington, 1987.

———

.

Richer

Than

We

Thought:

The

Material

Culture

of

Sixteenth-Century

St.

Augustine.

St. Augustine, Fla.: St. Augustine Historical Society, 1992.

———

.

Santa

Elena:

A

Brief

History

of

the

Colony.

Columbia: Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, 1984.

———. “Spain’s Sixteenth-Century North American Settlement Attempts: A Neglected

Aspect.”

Florida

Historical

Quarterly

59, no. 3 (January 1981):275–91.

Milanich, Jerald T. “The Western Timuqua: Patterns of Acculturation and Change.” In

Tacachale:

Essays

on

the

Indians

of

Florida

and

Southeastern

Georgia

during

the

Historic

Period,

edited by Jerald T. Milanich and Samuel Proctor, pp. 59–88. Gainesville:

University Presses of Florida, 1978.

Ribaut, Jean.

The

Whole

and

True

Discoverye

of

Terra

Florida.

A Facsimile Reprint of the London Edition of 1563. Introduction by David L. Dowd. Gainesvil e: University of

Florida Press, 1964.

proof

5

Republic of Spaniards, Republic of Indians

Amy Turner Bushnell

In 1573 and 1574, Philip II issued three sets of laws for the governing of Spain’s

empire in the Americas: the Ordinances of Pacification, of Patronage, and

of The Laying Out of Towns. In eastern North America, they marked the

end of the High Conquest, of would-be conquistadors such as Juan Ponce

de León, Pánfilo de Narváez, and Hernando de Soto, and of

adelantados

like

Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón, Tristan de Luna y Arel ano, and Pedro Menéndez

de Avilés. Future expansion would be Crown-controlled.

European fighting men were accustomed to band together under a cap-

proof

tain for a limited military objective, after which the company would divide

the spoils and disband to be free for other ventures. On the edges of Span-

ish empire, however, captains of conquest had been prolonging the wars

in order to sel their captives. A resolve to end this abuse lay behind the

king’s new policy of pacification through gifts and conversions. In future,

it would not be the military’s business to advance the frontier; its mandate

was to defend the advancing missionary. As patron of the church, the king

was equal y determined to reestablish control over the preaching orders to

whom Charles V had entrusted the spiritual conquest of the Indians. He

would make pastors from the “regular” clergy answer to his bishops as other

priests did. Both of these policies encouraged members of the Franciscan

Order, especial y, to strike out for fresh mission fields.

A third matter on the king’s mind was the vital flow of silver from Amer-

ica, threatened by the wild Chichimeca Indians in northern New Spain and

by foreign corsairs on the seaways of the Caribbean and the Gulf Stream. To

guarantee the deliveries of silver, the king resorted to a presidial system of

fortified outposts and ports. The soldiers and sailors stationed at a

presidio

,

like those in a royal

armada

, were regular troops on wages. Unlike conquis-

tadors, they were forbidden to take booty or captives; unlike

encomenderos

,

· 76 ·

Republic of Spaniards, Republic of Indians · 77

the traditional guardians of newly conquered lands, they were denied the

tribute and forced services of the conquered. In those places where the In-

dians accepted Christianity, presidios were reinforced by mission provinces

and converts provided a buffer zone against invasion and a source of rein-

forcements, provisions, and labor. Where the Indians rejected Christianity,

the frontier did not advance.

Spaniards posted to a “land renowned for active war,” whether as fighting

men, missionaries, or bureaucrats, were supported by a subvention known

as the

situado

, a transfer of royal revenues from one royal treasury in the

Indies to another, for purposes of defense. During the seventeenth century,

Florida’s situado came from Mexico City, capital of the viceroyalty of New

Spain, which also supported presidios on the road to the silver mines of

Zacatecas and in selected ports of the Caribbean and the Philippines.

Indians who could not be pacified by the sword, the gift, or the gospel

shared certain characteristics. Typical y, they were seasonal nomads, indif-

ferent to the sacraments and unwilling to settle down in farming vil ages on

the Mediterranean model. They had a high regard for individual liberty and

were governed by consensus instead of coercion. Final y, they could not be

quarantined from contact with Spain’s European rivals.

Every condition that made a pacification difficult was present in Spanish

proof

Florida; the colony would never lose its character as a military outpost. Yet

in the seventeenth century Florida enjoyed two periods of expansion and a

hinterland of productive mission provinces. This was possible because the

native societies were diverse. While some Florida peoples were seasonal y

nomadic, recognizing no power above the band, others were sedentary, with

caciques

and

cacicas

who exercised considerable authority. Through these

“lords of the land,” the Spaniards could implement a Conquest by Contract,

establishing an autonomous Republic of Indians to share the land with the

Republic of Spaniards, two castes united by their common al egiance to God

and the king. The notarized treaties of peace or trade, acts of homage or

submission, records of mission foundings, declarations of just war, and lists

of chiefs presenting themselves to the governor are evidence of the legal

side of pacification, the contracts, theoretical y voluntary, that the Spaniards

called into existence, recorded, and endeavored to enforce. But the success

of the Conquest by Contract and the corol ary Republics required a degree

of isolation and a flow of gifts that a maritime periphery could not easily

sustain.

Florida’s transformation from an

adelantamiento

to a royal colony was

gradual. Slowly, the situado was institutionalized, troops from the armadas

78 · Amy Turner Bushnel

were replaced by permanent garrisons, temporary treasury appointments

gave way to lifetime offices, and governors began to govern in person rather

than through lieutenants. When Santa Elena was abandoned in 1587, the

adelantado’s dream of a Greater Florida of transcontinental proportions was

tabled for the more practical goal of consolidation. Promotional activities

ceased, and settlement incentives to farmer families were discontinued.

If the new capital of St. Augustine was to be populated, the soldiers them-

selves would have to become family men, and Spanish women were scarce.

The answer was mixed marriage. By the turn of the century, half of the wives

in town were Indians, adding their genes to the pool of

floridanos

. Once an

increased birthrate had brought the sex ratio closer to equilibrium, consen-

sual unions between the Republic of Spaniards and the Republic of Indians

became less common and efforts were made to enforce segregation. Indians

could not come to St. Augustine without a pass, and non-Indians traveling

on the king’s business could stay no more than three days in a native town

and must sleep in the council house. These restrictions did not apply to the

Franciscans, who resided among the Indians and could not leave their posts

without permission.

Persons of African origin added a third ethnic element to the colony.

At one time, more than fifty black “slaves of the king” were at work on the

proof

wooden fortifications, and numerous families had African domestics. Tak-

ing advantage of lapses in security, many of the enslaved escaped to live

among the Indians or in maroon communities. Free blacks and mulattoes

occupied the lower social levels of the Spanish community, being Spanish

in language, faith, and fealty.

Although Philip II would have preferred it otherwise, the Spanish empire

was cosmopolitan and its borders were permeable. By the unwritten rule of

“foreigners to the frontiers,” St. Augustine was home to several nationalities.

Many of the colony’s ship captains, pilots, and merchants were Portuguese,

who in the Indies were likely to be

conversos

of Jewish background, and

other inhabitants might be Dutch or German artillerists, a French surgeon,

or an English pirate turned carpenter. Like the Spanish presidios in North

Africa, St. Augustine functioned as a penal colony, a place of exile for un-

ruly officers, trouble-making friars, and sentenced criminals, or

forzados

.

Many of the soldiers, too, were

involuntarios

, with records as debtors, petty

thieves, vagrants, and rioters. Those from New Spain were further stigma-

tized, their mixed racial heritage being associated with illegitimacy.

Final y, St. Augustine was a seaside presidio, the only coast guard station

along 600 miles of strategic sea lane. After a storm, its vessels scoured the

proof

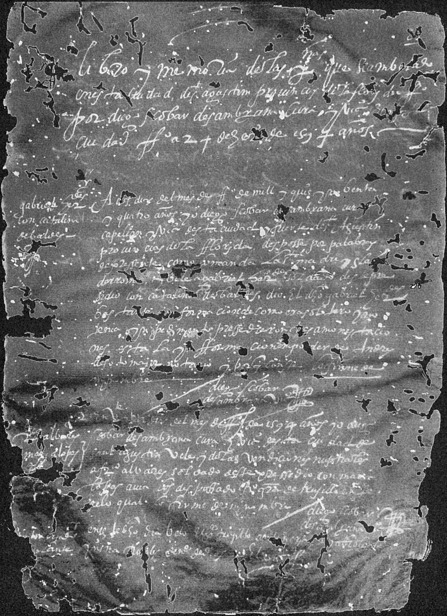

The oldest European document of North American origin preserved in the United

States is this page of the surviving Parish Registers of St. Augustine, Florida. Dated 24

January 1594, the first entry records the marriage of Gabriel Hernándes, “a soldier of

this presidio,” and Catalina de Valdés. The officiating priest was the pastor of the parish

church and chaplain of the garrison, Diego Escobar de Sambrana. The registers form a

continuous record to the present day of Catholic life in the city. The fate of entries from

1565, when the parish was founded, to 1594 is not known.

80 · Amy Turner Bushnel

coast for castaways, cargoes, and naval artil ery. Their presence reassured

voyagers in the Fleet of the Indies, sailing northward on the Gulf Stream

60 miles offshore. When not escorting the Fleet, frigates from the presidio

sailed to Havana and Veracruz for supplies, to Spain with dispatches, or

to show the flag and trade with the natives in Florida’s deepwater harbors,

along the inland waterway, and up the St. Johns River.

As advised in the Ordinances of Pacification, the Franciscans charged

with the spiritual conquest of Florida took their “flying missions” directly

to the Indians, raising crosses on town plazas, preaching, and inviting the