The History of Florida (21 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

Except for the instal ation of the Spanish governor or his lieutenants as su-

preme authority over each native polity, a traditional roster of native politi-

cal officials remained largely unchanged and unchal enged. Such differences

doubtless were among the reasons that the new faith seemingly held stron-

ger sway over Florida’s natives than it did over New Mexico’s Pueblo during

an equivalent span of time, that Florida’s mission structures retained their

original simplicity, and that the natives’ council house continued to be the

mission vil ages’ most impressive and most frequented building.

Members of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), who made the first mission

efforts in Florida, uniformly met resistance, even though the missionaries

94 · John H. Hann

were accompanied by soldiers. Jesuits are members of a religious society

founded in 1534 and devoted to missionary and educational work. They

worked briefly at single sites among southwest Florida’s Calusa, the Miami

area’s Tequesta, the Escamacu in the region of Beaufort, South Carolina, and

at Tupiqui and one or more other places in Guale. Some of the resistance

was doubtless a legacy of de Soto’s brutal passage through Florida or was

influenced by the natives’ contact with the French just before the Jesuits’ ar-

rival. But, more fundamental y, the Jesuits met resistance to their message

everywhere as soon as they spoke il of the natives’ deities or when they

revealed that the natives would have to abandon polygyny, sororal marriage,

and other customs on becoming Christians. Soldiers’ demands for food and

friction with natives also handicapped the Jesuits’ efforts. The soldiers’ kill-

ing of two successive head chiefs and other nobles at Calusa precipitated

flight by the rest of the inhabitants, which ended the mission effort among

them until late in the seventeenth century. The Jesuits viewed friction or

hostilities between soldiers and natives as insuperable obstacles, responsible

for their failure.

In reality, from Calusa and Tequesta to Guale and Escamacu, the Jesuits

dealt with natives whose confidence in their own value system and world-

view had not been shaken sufficiently to make them susceptible to the Euro-

proof

pean Christian message. However much Jesuits might browbeat the Indians

with their superior training in rhetoric and logic, they could not move them

to abandon their beliefs. Everywhere in Florida, Jesuits made their efforts

before the time was right. For the Calusa and other nonagricultural Indians

of south Florida, the time would never be right. The Indians’ killing of Jesu-

its who had gone to the Chesapeake Bay region caused the withdrawal of the

society from Florida in 1572. But their work among the natives had ceased

prior to their leaving.

Down to 1595, little is known about the activity of the first Franciscans,

who came in 1573. Franciscans were members of the religious community

formal y cal ed the Order of Friars Minor, founded in Italy by St. Francis

of Assisi in 1209. They dedicated themselves especial y to preaching in the

growing cities of medieval Europe, to missions among non-Christians, and

to charitable work. They emphasized humility and were usual y referred to

as friars, a term derived from the French word for “brother.”

In Florida the friars had their earliest success among Saltwater and Fresh-

water Timucua living near St. Augustine and on the St. Johns River in the

latter part of the 1570s. Surprisingly, Jesuits appear to have made no effort in

those regions despite the Freshwater Timucua’s friendship with Menéndez

The Missions of Spanish Florida · 95

de Avilés from the beginning and despite his friendly relations with some

Saltwater Timucua as wel . At the start, as Eugene Lyon has noted, a lan-

guage barrier, a lack of trained missionaries, and unsettled relations with

Saltwater Timucua limited religious contact. The Jesuits may have passed

over the St. Augustine region initial y because one of the first three to arrive

was killed by Timucua-speaking Mocama just to the north of the mouth of

the St. Johns River when he was stranded on shore with some sailors.

Nombre de Dios is considered the oldest of Florida’s enduring missions.

Work among its people and the Freshwater Timucua of San Sebastian, just

to the south of St. Augustine, appears to have begun around 1577. But people

of both vil ages attended Mass in St. Augustine until 1587, when the first for-

mal missions, known as doctrinas, appear to have been established in both

vil ages. San Juan del Puerto, at the mouth of the St. Johns River, was also

founded by 1587. A bridgehead represented by the Franciscans’ conversion

of a Guale head chief disappeared quickly when that chief was killed by a

nephew of another chief whom he had confronted over disrespect for his

authority. The Spanish governor’s reluctant hanging of the nephew at the

insistence of the deceased chief’s wife precipitated revolt from Guale north

to South Carolina’s Escamacu-Orista. The revolt precluded missionary work

in that region at least until 1588, when San Pedro Mocama was founded

proof

on Georgia’s Cumberland Island. Family ties between chiefs of Nombre de

Dios, San Juan, and San Pedro may have facilitated mission activity at this

date, as had arrival of a new band of friars in 1587. By 1588 at least five mis-

sions and a number of outstations, or visitas, existed among Freshwater and

Saltwater Timucua.

Arrival of more friars in 1594 permitted a major effort among the Guale.

Six friars were working there by 1597. By then friars were making sorties

into hinterland Timucua vil ages whose chiefs had responded favorably to

a new governor’s invitation to render obedience to his king and to receive

gifts the king had sent to those ready to give that obedience. But later that

same year, a general uprising of the Guale interrupted the mission effort, as

they killed five of their six friars and carried off the sixth one to an inland

town to serve his captors as a slave. An imprudent friar’s effort to block

the rise to head chieftainship of a young Christianized chief who refused

to abandon polygyny precipitated the trouble, but the support given the

uprising suggests that the discontent involved more than the sexual mores

of one individual. The friars’ baptism of natives before telling them clearly

about the scope of the obligations they were assuming in accepting baptism

and about the tribute and labor demands of Spanish civil authorities were

96 · John H. Hann

factors as wel . In the uprising’s wake, the governor reduced the maize trib-

ute for the Mocamas to a symbolic six ears for each married Indian. A young

Spaniard shipwrecked on Guale’s coast in 1595 placed part of the blame on

earlier atrocities committed by soldiers on punitive expeditions. The gover-

nor’s sustained campaign of fire and blood eventual y broke the solidarity of

the Guales. A majority, coalescing behind a new leader, sued for peace and

agreed to capture or kill the rebellion’s initial leaders in the inland region

where they had taken refuge to escape Spanish retaliation.

Rapid growth resumed in 1607, when arrival of a few new friars made

it possible to capitalize on the interest in Christianization shown by some

among the hinterland tribes ten years earlier. In that year the friars estab-

lished the first new missions among Timucua-speakers known as Potano

living in the vicinity of Gainesville. Within several years, a friar descending

the Santa Fe to the Suwannee established a mission on the Gulf in a vil age

named Cofa at the mouth of the Suwannee. From Potano, friars moved into

Columbia County to work among Timucua-speakers identified as Utina. In

1623 friars began to work among other Timucua-speakers known as Yustaga,

living between the Suwannee and Aucil a Rivers. Friars also resurrected the

Guale missions and began work in the remaining Timucua-speaking prov-

inces of mainland south Georgia’s coast and hinterland, Acuera along the

proof

Oklawaha, and Ocale south of Potano. Two friars began formal missioniza-

tion of Apalachee in 1633. It was the last of the major mission provinces to

be established until late in the century. A mission at Mayaca on the St. Johns

River south of Lake George consolidated work done by visiting friars prior

to 1602.

Evidence to account for the change of heart that made that expansion

possible is fragmentary. In addition to the attraction of the gifts being of-

fered, a series of Spanish successes against French intruders enhanced the

Spaniards’ image as allies worth cultivating. A personal embassy by a lead-

ing Christianized Indian from Nombre de Dios may have swayed Utina’s

most prestigious leader. Use of a mailed fist to punish the killing of Span-

iards brought a reversal of hostility on the part of the Potano and Surruque.

For some, such as Utina’s head chief and Apalachee leaders who asked for

friars, the change of heart may have been abetted by loss of faith in the na-

tive religious system as a bulwark for their power. Such chiefs may have

viewed exotic goods provided by Spaniards and esoteric knowledge and

skil s Spaniards made available as enhancing the chiefs’ prestige in the eyes

of their people. That may explain the eagerness of many of the early con-

verts to learn to read and write and the Utina chief’s willingness to permit

proof

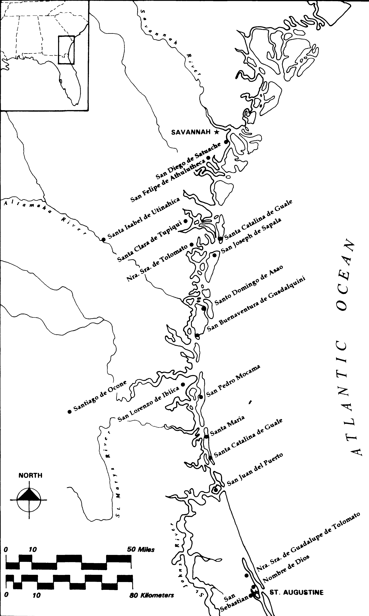

Names and locations of Franciscan missions at St. Augustine and north along the

Atlantic coast in the seventeenth century.

98 · John H. Hann

destruction of the idols in five vil ages under his immediate jurisdiction.

The Apalachee leaders’ request for friars was motivated in part at least by be-

lief that a Spanish alliance would enable leaders to regain control over their

subjects that they had lost. For that and other reasons, Spanish authorities

delayed the missionization of Apalachee for a generation.

Florida’s missions contrast with those of California in that their friars

general y did not alter the natives’ settlement pattern, which consisted of

a large central vil age under a head chief, smaller ones under subordinate

chiefs, and still smaller chiefless hamlets. Friars established their doctrinas

in the head vil ages, visiting subordinate vil ages and hamlets to give in-

structions and building churches in some of the subordinate vil ages. Some

such subordinate vil ages eventual y became missions, at least for a time. In

1602, however, a friar advocated consolidation of the many small hamlets

surrounding the coastal missions. There is no indication that it was done,

but as populations dwindled, consolidation may have occurred in some

cases. In Apalachee, best known of the mission provinces, the settlement

pattern persisted virtual y intact until destruction of the missions in 1704.

Guale is the one area where consolidation and extensive moving about of

missions is known to have occurred. Between 1604 and the 1670s, many

Christian Guale from former mainland doctrinas and their subordinate vil-

proof

lages moved to the islands off Georgia’s coast. Little is known of the timing

and circumstances of those moves, except for the Tolomato, whose chief led

the 1597 revolt. In the 1620s, the governor pressured its inhabitants to move

to a site near St. Augustine to provide ferry service and assist in the unload-

ing of ships at St. Augustine. In this earlier period, the desire for greater

security from attacks by Westo and Yuchi probably motivated such moves.

A later consolidation on Amelia Island resulted from British attacks.

Florida’s inland missions in general were not missions of conquest as were

those of the coast to a degree. This difference also sets those missions apart

from those of New Mexico and California. Soldiers did not accompany the

first friars who began work in the hinterland, following a policy laid down

explicitly by the Crown in that era. This seemingly posed no problem for

the friars in Utina, but the situation was different in Potano, Yustaga, and

Apalachee. Even though Potano’s head chief had been baptized in St. Au-

gustine prior to the launching of the formal mission effort in his land, his