The History of Florida (15 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

the Jesuit mission were withdrawn, and the attempt to evangelize the Calusa

ended.

The abandonment of the south Florida forts and missions foreshadowed

a general northward relocation of Menéndez’s Florida enterprise. Forsak-

ing the effort to exploit the St. Johns River and other inland waterways, the

Spaniards evacuated San Mateo and shifted the garrison to a new fort, San

proof

Pedro de Tacatacuru, on Cumberland Island. The new fort would anchor the

route from St. Augustine to the colony’s new center, Santa Elena. The Jesuits,

in an attempt to evangelize the Guale and the Orista, moved north with the

soldiers.

From Santa Elena the adelantado sent Captain Juan Pardo on two long

expeditions westward to the Appalachian Mountains. Pardo’s mission was

to scout fertile lands for future economic development and to find the route

to the silver mines of Guanajuato and Zacatecas in México. On his first jour-

ney in December 1566, Pardo proceeded into present-day North Carolina,

then westward to the foot of the Blue Ridge. There, at a place called Joara,

he founded the city of Cuenca and left a garrison in Fort San Juan under

Sergeant Hernando Moyano. The lands there, said the Spanish captain, were

“as pretty as . . . the best in Spain.”2 At Guatari, near today’s Salisbury, North

Carolina, Pardo noted a particularly fertile area, where he left four soldiers

and a secular priest, the company’s chaplain Sebastian Montero, to evange-

lize the Indians.

When he returned to Santa Elena, Pardo told Menéndez of his inland

discoveries, and the adelantado fixed upon the area of Guatari for his own

personal land grant, which would undergird his family’s future prosperity

66 · Eugene Lyon

and make him a marquis. Sent out a second time, in September 1567, Pardo

took with him as interpreter the young Frenchman Guil aume Rouffi. He

fol owed much the same route as before, finding rich bottomlands near

present-day Ashevil e. He then went westward across the mountains into

eastern Tennessee, to the populous town of Chiaha. After that, concerned

about being attacked by powerful Indian groupings, Pardo did not press on

to Coosa and Tascaluza, waypoints for him on the road to México. Instead,

the Spaniards turned back and returned to Santa Elena.

Now, Menéndez concluded, in order to begin to populate the vast areas

of coastal and inland Florida, it was time to begin its serious settlement.

From the beginning of his enterprise, the adelantado had planned to import

settler-farmers. One of the clauses in his contract required him to establish

two towns, to bring livestock, and to carry 500 settlers to Florida. In his first

expedition, 138 of his soldiers—carried at his own expense—were craftsmen

who represented many of the trades of sixteenth-century Castile. Another

117 of his soldiers were farmers, and 26 brought their wives and children.

In their agreements with the adelantado, the soldier-farmers were prom-

ised by Menéndez that he would “give them rations in the said coast and

land of Florida, and lands and estates for their planting, farming and stock-

raising, and divisions of land, in accordance with their service and the qual-

proof

ity which each one possesses.”3

After he expelled the French, established his Florida supply lines, and put

down the soldiers’ mutinies, Menéndez contracted with one Hernán Pérez,

a Portuguese, to bring farmers from the Azores. In his arrangements with

this and other settler groups, the adelantado promised to “give them their

passage and pay for their freight. Having arrived at this land, I wil give them

lands and estates for their farms and stockraising, and within two years a

dozen cows with one bul , two oxen for plowing, twelve sheep, and the same

number of goats, hogs and chickens, and two mares and one farmhand,

and a house constructed, with its winepress, and a male and a female slave,

and vineshoots to plant.”4 Menéndez then indicated that the settlers would

sharecrop with him until the costs incurred were paid out. He added, “I do

not have the capability to do this, but I believe that there will be merchants

who, once they know how good this land is for cultivation, . . . might wish

to put in a part of their wealth in that profitable agricultural enterprise—in

order to settle themselves on large

haciendas

of sugar mil s, livestock and

farms of bread and wine.”

This arrangement fell through, but in 1568 Menéndez had the funds in

hand to put his plan in motion with settlers from the Iberian peninsula. The

Settlement and Survival · 67

potential Florida settlers in Castile were mostly small farmers,

labradores.

Although it had a number of cities, Castile was an essential y agricultural

and pastoral area. Most people worked the land, raising sheep and hogs for

food, donkeys, mules, and horses to serve as work animals, and cattle. They

cultivated gardens and orchards and had widespread wheat, vineyard, and

olive plantings. Spanish agriculture was therefore both extensive and in-

tensive. Except for a few fertile plains and the lush green Cantabrian north,

Castilians were accustomed to marginal soils and a dry, harsh climate. Wa-

ter was rare and precious; in the Castilian language, the words for

wealthy

and for

abundant

waters

were the same:

caudaloso.

Castilian emigrants to

the Americas sought rich and well-watered lands for their husbandry and

hoped to find them in Florida.

In the provinces of Extremadura and upper Andalucía, Menéndez re-

cruited a number of farmers who came with their wives and children to

Cádiz, where Pedro del Castillo arranged for them to board ship for Florida.

After a sharp skirmish with the Casa de Contratación over permission to set

sail, Castillo obtained royal permission for two ships, the

Nuestra

Señora

de

la

Vitoria

and the

Nuestra

Señora

de

la

Concepción,

to depart. Many of the settlers aboard came from Mérida and the area of Guadalcanal.

In the spring of 1569, the ships reached Florida, and 273 settlers landed

proof

in St. Augustine; 193 of these were sent quickly to Santa Elena. Once estab-

lished there, the settlers built houses, worked at their lands and livestock,

engaged in trade, and involved themselves in the city government. On 1

August of that same year, thirty-six households were enumerated in Santa

Elena, together with four houses for single men. By October, 327 persons,

including the settlers and soldiers, lived there. The families that had come

to build their hearths and futures in La Florida were participants in a major

transfer of Hispanic culture.

Sixteenth-century Florida society was broadly representative of several

regions of the Spanish homeland. It presented a cross section of the trades,

crafts, professions, and social strata of early modern Castile. It was a def-

erential, hierarchical society; goods inventories disclose how real and per-

sonal property in Spanish Florida general y mirrored the stratification of

the community. Ordinary soldiers and sailors had few possessions, although

some had musical instruments and acted as moneylenders. The servant Juan

Rodríguez slept on the floor outside his mistress’s St. Augustine rooms. At

the other end of the social scale, Adelantado Menéndez kept court like a

viceroy, with noble retainers and liveried servants. When Menéndez and

his wife, Doña María de Solis, moved to Santa Elena in 1571, they shipped

proof

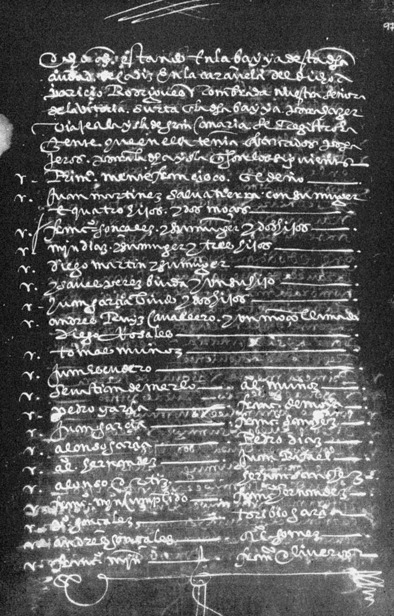

The surnames of many of the first European inhabitants of Florida are given in a four-

page document dated 27 September 1568, the first page of which is shown. The docu-

ment lists the names of 209 farmers, their wives, children, other relatives, and servants

from the Spanish province of Extremadura who sailed for Florida in two caravels out

of Cádiz in October 1568. The names given in the document are: Sedeño, Martínez

Salvatierra, González, Díaz, Martín, Perez, García, Ruyz Cavallero, Muñoz, Escudero, de

Merlo, de Moya, Sánchez, Hernández, Ortíz, Martin Cumplido, Gómez, Oliveros, de Vía,

Martín Texada, Olivares, de las Eras, Calvo, Asencio, de la Torre, Rodríguez, de Herrera,

de Berrío, Domínguez, Pinto, Rueda, de Sellera Porra, de Segovia, González Dorado,

Romero, Martín Silvestre, Serrano, Viejo, Gordillo, Mener, de la Rosa, Ruyz, Alonso, de

Olmo, Sigüenza, Tristán, López, and Azaro.

Settlement and Survival · 69

luxurious household furnishings: ornate rugs and wall hangings, beds and

bedding, and fine table linens and plate. The inventories also describe the

sumptuous clothing and elegant accessories imported by the Menéndez

family and other noble persons in Florida. The archaeologist Stanley South

found the remnants of gold embroidery at Santa Elena, together with jew-

elry and a fragment from a costly Ming Dynasty porcelain wine ewer. The

import lists also feature majolica tableware and food delicacies: dates, al-

monds, quince-paste, and marzipan. But the class lines evidenced by those

goods were tempered by Spanish individualism and by the upward mobility

many Florida citizens displayed.

This was, moreover, a corporate society. The Florida immigrants shared

many unifying beliefs, traits, and customs, which included their Castil-

ian language. Al were communicants of the Tridentine Roman Catholic

Church; many of the men belonged to one of the Florida confraternities,

whose membership cut across social lines. Those laymen organized funer-

als, marched in processions, and supported their members’ widows. The

sacramental Mother Church dominated the daily life of Spanish Florida; the

very hours and days were numbered by the church bel s and the Christian

calendar. An inventory of the parish church included a fine painted retable

and gilded altar cross. Menéndez’s deeds in expelling the French “Luther-

proof

ans,” as all Protestants were called, called forth praise from Pope Pius V. The

adelantado then asked the pope for special indulgences for his colonists

and soldiers who might die without confession during the events of the

conquest.

For their part, the soldiers were the bearers of a long military tradition,

formed since the time of Isabel and Fernando. They and their officers were

the king’s shield against his enemies, but the military had another, darker

side; the mutinies of 1566 had been caused by Spanish veterans of wars in

Italy and France, who were accustomed, as Menéndez said, to “banquets,

booty, and wine.”5

Qualifying as

vecinos,

or city electors, the citizens of St. Augustine and

Santa Elena enjoyed the ancient Castilian municipal liberties. Everyday life

was governed by the municipality, which determined prices, established

weights and measures, controlled the local court for civil and criminal mat-

ters, and regulated the marketplaces.

The surviving body of Florida lawsuits depicts many of the realities of

daily life and the prevailing sixteenth-century social climate there. One

case, for instance, involved a litigious tailor named Alonso de Olmos, who

sued the governor for libel. Olmos claimed that Governor Don Diego de

70 · Eugene Lyon

Velasco directed epithets at Olmos’s daughter as he ejected her from a reli-

gious procession. Moreover, he contended, the governor had also insulted

him with the taunt “See the Lutheran going to the synagogue!”6 In another

case, the settlers sued the governor for payment of the clothing, food, and

rental owed them; prosperous with goods, the settlers had been extending

credit to soldiers and wanted repayment. Velasco was authoritarian in his

dealings with the Indians but took care to provide them with the usual gifts

and presents.

Documents disclose the vigorous economic life of sixteenth-century

Spanish Florida. The farmers from Spain learned to cultivate corn, which

was at first imported or bought from the natives; it slowly replaced wheat

and cassava as the staple carbohydrate in the colonists’ diet. Later, wheat