The History of Florida (10 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

have attracted persons from colder climes, creating tourism and retirement

industries that capitalize on at least those aspects of the state’s ecology. Even

so, some characteristics of the region’s ecology—notably periods of drought

· 41 ·

42 · Paul E. Hoffman

and tropical storms—are beyond modern control. This chapter explores the

ecology of the Floridas, especial y with regard to the colonial and early-

nineteenth-century periods when it had the greatest impact on human lives.1

The late-sixteenth-century Spanish royal cartographer Juan Lopez de

Velasco claimed as Spanish Florida (La Florida) the vast region running

from the cod fisheries of Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and northern New

England to as far south as the Florida Keys and west along the Gulf coast to

the Soto La Marina River in Mexico. Inland, it reached as far west as the un-

defined eastern edge of New Mexico. If this La Florida had a northwestern

boundary, it was the supposed arm of the Pacific Ocean that was thought

to reach deep into the continent to the north of New Mexico to an elusive

point west of the Appalachian Mountains.

In sixteenth-century practice, those grand, vague boundaries shrank to

encompass the coastal and piedmont zones of the modern states of Virginia,

North and South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama; the Appalachian Moun-

tains of the Carolinas; southeastern Tennessee and northern Alabama; an

undetermined part of the Gulf of Mexico’s northern coast and the Missis-

sippi Valley; and peninsular Florida. This definition arose from coastal ex-

plorations and the de Soto expedition’s peregrination through the Southeast

(see map

on p. <000>[refers to fig. 2.4]). In legal and diplomatic terms, it

proof

was a claim based on discovery and possession taking as wel as the so-

called Papal Donation and the Treaty of Tordesil as of 1494. Yet within this

area, effective occupation and influence extended only as far as Spanish

settlements or missions or active trade did, which in the sixteenth century

effectively meant coastal areas of peninsular north Florida, Georgia, and

South Carolina, and, briefly in the 1560s, the Carolinas’ piedmont (see map

on p. <00>[refers to fig. 6.1]). During the seventeenth century, the area of

active missions expanded into various parts of the interior of the penin-

sula (see map

on p. <00>[refers to fig. 6.2]). Trade via Native American

intermediaries may have reached farther into the backcountry that is today

western Georgia and Alabama, but we know little about it. That is, Spain’s

La Florida in reality was based on effective occupation of only a small part

of the expansive land claims its diplomats sometimes made in negotiations

in Europe or that its maps and geographers laid down.

As chapters 4, 5, 6, and 8 show, epidemics among the Native American

populations (limiting the area of mission work and trade), wars, and Euro-

pean treaties slowly reduced La Florida’s effective extent. When the British

took over the colony in 1764, they decreed the northern limit of today’s state

(31° North and the course of the St. Marys River) but did not accept the

The Land They Found · 43

Franco-Spanish understanding of 1723 that the Perdido River marked the

line between Spanish La Florida and French La Louisiane. Thirty-one years

later, the United States accepted and then surveyed the 31° border under the

Treaty of San Lorenzo of 1795 (Pinckney’s Treaty). Final y, in 1822, when

Congress organized the Territory of Florida, it used the Perdido River to

mark its western boundary.

The Spanish mariners who first saw the shores of La Florida encountered

what appeared to their untutored eyes to be unbroken forests of pines and

mixed pines and hardwoods running from the sea to the great stands of

fire-tolerant longleaf pine trees that marked the edges of the piedmont in

the Carolinas and Georgia and covered the northern highlands of the pen-

insula. Along the shore and on the backs of coastal islands were hammocks

of live oaks where soils were appropriate. The river valleys that ran to the

sea were thickly grown with multiple hardwood species. On the piedmont,

the oak-pine-hickory forest appeared, while on some slopes of the Appala-

chian Mountains the dominant forest was the oak-hickory-elm association

now largely lost to Dutch elm disease. Appearing uniform, these vast bands

of forest were in fact mosaics of many floristic communities, communi-

ties determined by soils, rainfal , drainage, temperature, and the shaping of

the forests by lightning fires, insects, and Native American agricultural and

proof

hunting practices, including the use of fire. Faunal diversity accompanied

this floral diversity, although most species were too small for use as food.2

Less clearly in peninsular Florida than farther north along the coastal

plain, the rising and retreating of the Atlantic and the warping of the North

American geologic plate have shaped as many as a dozen step-like, if dis-

continuous, “terraces” in what geologists classify as three sections (lower or

outer, middle, and upper or inner) of the coastal plain. The soils on these

coastal terraces were once back barrier marsh surfaces, bay bottoms, and/or

areas of al uvial deposition and are general y acidic sands of low fertility and

high moisture content during the rainy season. In general, they are classified

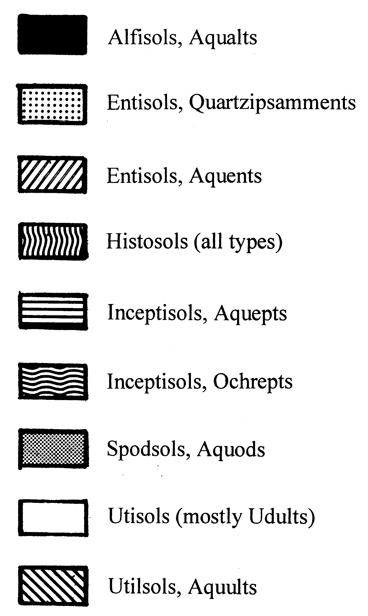

as Aquults, although areas of Humaquepts occur along the Georgia coast.3

Inland swamps, marshes, and low areas that flood during the rainy season

reflect this geologic history. Hardpans (horizons of nearly impermeable

clay) underlay some areas, notably on the east and west coasts of Florida

where the soils are Aquods. These hardpans result in rainy-season flooding

and the famous pine flatwoods that some British-era “planters” exploited

for naval stores and that today support the pulpwood industry where sub-

divisions have not sprung up. Scarps or even sand hills (in Georgia and

the Carolinas) mark the edges of the terraces and provide gradations in

44 · Paul E. Hoffman

moisture from wetter (close to the water) to drier on the uplands, gradations

that define ecotones where floral and faunal diversity is greater than on the

terrace below or above. Ecotones can also be found around ponds and lakes

and along stream beds, especial y in central Florida.4

The Piedmont has a similar topography of terraces although the soils are

more fertile and better drained by numerous small streams flowing into the

rivers that drain to the east or south. In general, the soils are mostly reddish

Udults. Native Americans and modern farmers used and use the friable,

quality soils of the valley floodplains associated with the smaller streams.

De Soto’s men (1539–40) and Juan Pardo’s soldiers (1566–68) recognized

these areas as places suitable for Spanish agricultural settlement.5 Histo-

rian Eugene Lyon believes that had Pedro Menéndez de Avilés lived long

enough, he would have claimed the upper Wateree River Valley (explored

by Pardo) as part of the marquisate Philip II had promised him if he success-

ful y settled La Florida.6 Had Spanish settlement developed in this area in

the Carolinas, the history of Florida might have unfolded quite differently.

Instead, the Spanish towns of Santa Elena (1566–87; Parris Island, South

Carolina) and St. Augustine were built on the sands of the Atlantic coastal

plain; that is, on soils with limited agricultural potentials, aside from run-

ning cattle in the pine woods, characteristics that, along with the absence

proof

of minerals, limited Spanish interest in the colony. Only Florida’s strategic

location on the Bahama Channel and the pleas of the Franciscan missionar-

ies prevented its abandonment in the early seventeenth century.7 For most

of the rest of the first Spanish period, the colony depended on its

situado

(civil list or subsidy) as the main engine of its economy, although Apalachee

is known to have exported deerskins and foods to Havana. During the Brit-

ish, second Spanish, and early American periods, a more diverse economy

gradual y built up based on the export of hides, oranges, naval stores and

timbers, and cotton produced at various places mostly north of the I-4 cor-

ridor of today. Cuban fishermen developed that industry along the lower

west coast, but it did not depend on the qualities of soils.

In peninsular Florida, geologists have identified sections of as many as

five of the eight terraces of the lower coastal plain in the strip of land be-

tween the Atlantic Ocean and the 15-meter (50-foot) contour west of the

St. Johns River and general y north of the Tampa–Daytona Beach line. The

higher ground of the flatwoods of the upper St. Johns and Kissimmee River

basins as well as the flatwoods between Sebring and Lake Okeechobee, and

in southwest Florida along the Caloosahatchee River and between Fort My-

ers and Tampa Bay are also classified as parts of these coastal terraces. On

The Land They Found · 45

the western side of Florida’s central ridge north of Tampa Bay, some of the

terraces also are evident, for example on State Highway 24 between Cedar

Key and Gainesville. The terraces of the middle coastal plain that are no-

table features of Virginia and the Carolinas (three and four terraces, respec-

tively) but less so in Georgia (two terraces) continue in Florida to form four

identifiable terraces east of the Haines City Ridge in central Florida and

west of the Trail Ridge feature (and 15-meter contour) of northern Florida

and southeastern Georgia. Less certain is whether the highest elevations

of Florida’s central ridge should be classed as continuations of the upper

coastal plain found in Virginia and the Carolinas.

Whatever the relationship of the central ridge to geologic features farther

north, the western highlands and the Mariana, Tal ahassee, and Madison

Hills are part of the south and southeastward tilted “southern” or Tifton

uplands that extend into adjacent parts of southwestern Georgia. Streams

and rivers have carved this upland into hil s and val eys with general y mod-

erate (10–25°) slopes. The soils are mostly Udults, with red-yel ow sands

over clayey subsoils west of the Madison Hil s and gray-brown sandy loams

on those hil s. Early-nineteenth-century atlas maps described these hil s as

having “good soils” because they, like similar soils on the central Florida

ridge, have moderate to good fertility and general y excellent drainage. The

proof

Tal ahassee Hills were home to the Apalachee Indians. In the nineteenth

century, cotton plantations were established on al three sets of hil s. Be-

cause of the slopes, these hil s have as many as thirty-five species of trees

per acre and general y support one of the more diverse ecological areas in

the Southeast.

The central ridge and its outlying hil s to the east and south are general y

covered with gray-brown sandy soils (Quartzipsamments) of varying slope.

The so-called Arredondo-Kendrick-Mil hopper Association of red-yellow

sandy loams (Udults) cuts across the ridge in a north to south pattern. Both

regions or soil groups are moist to well drained and of moderate fertility.

The natural climax forest varies with moisture but is general y various kinds

of pines with scrub oaks (on drier soils), although areas of oak and hickory

hardwoods occur on the Arredondo-Kendrick-Mil hopper Association soils

and on the more moist slopes. The central ridge was home to the majority of

Florida’s precolonial Timucuan speakers, the late-eighteenth-century home

of the Seminole and Miccosukee, and is today an area of increasingly dense

settlement.

North of a line from Fort Myers to the Fort Pierce Inlet, and south of the

Central Ridge, are superficial y gray, very acidic infertile soils (Aquods) that