The History of Florida (5 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

ary 1512. Born to a noble family in Val adolid, Juan Ponce at age nineteen

shipped to the Caribbean on Columbus’s second voyage in 1493, and, after

New World seasoning, he conducted the conquest of Puerto Rico in 1506–7,

becoming its governor in 1509. In 1512 he was deposed on a technicality by

Columbus’s older son, Diego Colon, and, finding himself wealthy and with

time on his hands, he accepted an asiento to discover and conquer the land

“to the north” called Bimini. According to legend, Bimini contained a foun-

tain of waters that rejuvenated old men, the so-called Fountain of Youth. It

should be emphasized that those mythical waters were not mentioned in

Juan Ponce’s charter from Fernando II, which was meticulously detailed

in its specification of the expedition’s purpose and goals. Nor were they

mentioned in any firsthand report or narrative, although the one extant de-

tailed source for Juan Ponce’s voyage of 1513—historian Antonio de Herrera

y Tordesil as, who in 1601–15 published a chronicle of Spanish New World

proof

explorations—states that on the return end of that voyage, Juan Ponce sent

one of his ships into the Lucayan, or Bahama, chain to search for “that cel-

ebrated fountain which the Indians said turned men from old men [into]

youths.”1 This probably was a gloss by Herrera based on an unsubstantiated

account by Peter Martyr. Probably more important to Juan Ponce were gold

and the glory of conquest, the lust for which drove all conquistadors of the

period.

On 3 March 1513, Juan Ponce left Añasco Bay on the western side of

Puerto Rico with two caravels and a bergantina. Notable among the crews

and passenger list were thirty-eight-year-old Antón de Alaminos, the most

experienced pilot in the islands; two women, Beatriz and Juana Jiménez,

who probably were related; two African freemen, Juan Gárrido and Juan

González [Ponce] de León; and two unnamed native Taíno seafarer-guides

from Puerto Rico.

Alaminos set a course of northwest a quarter by north that took the three

ships seaward up the eastern edge of the Lucayans as far as the northernmost

charted island of San Salvador (the Lucayan Guanahaní that was Colum-

bus’s first landfall in 1492), which they reached after eleven days. They were

at sea again on the same base compass heading, but in unknown waters,

20 · Michael Gannon

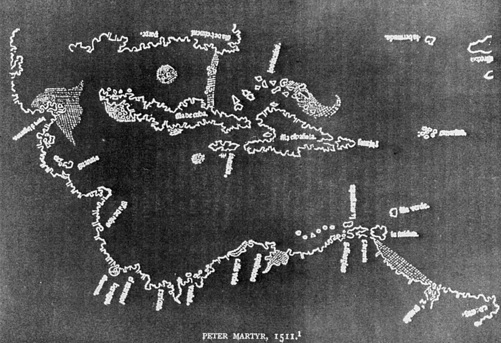

Map of the Caribbean published by Peter Martyr in 1511. The landmass to the north of

Cuba is named

isla

de

beimeni

parte.

Its placement, and what appear to be keys de-

scending from it, have led some historians to speculate that it is a depiction of Florida,

drawn from navigators’ reports, two years before the voyage of Juan Ponce de León.

proof

on Sunday, 27 March, when the crews and passengers observed the feast of

Easter. That day, too, they sighted an island, which probably was Eleuthera.

From that point, as indicated by a recent resailing of the route to test the pre-

vailing winds and currents, Alaminos took a new heading of west-northwest

through the New Providence Channel and passed well below the southern

cape of Great Abaco and the whole of Grand Bahama. This course placed

the vessels out of the sight of land for the next six days. When they crossed

the three-knot Gulf Stream, the Spanish hul s were carried north faster than

they shouldered west, with the result that on 2 April they made landfall on

what turned out to be the Florida shoreline. The most recent study con-

tends that they were at a point just south of Cape Canaveral, probably near

Melbourne Beach, where they anchored in eight

brazas

(forty-four feet) of

water.2

Herrera describes what fol owed: “And thinking that this land was an

island, they called it

La

Florida,

because it was very pretty to behold with

many and refreshing trees, and it was flat, and even: and also because they

discovered it in the time of Flowery Easter [Pascua Florida], Juan Ponce

wanted to agree in the name, with these two reasons.”3

First European Contacts · 21

Juan Ponce went ashore to take formal possession of the “island,” but

there is no indication in the record that he encountered people indigenous

to the site. After remaining in the region for six days, he raised anchor on

8 April and sailed south along a featureless coastline. On 21 April, he made

his second great discovery, though it is doubtful that he and Alaminos real-

ized its dimensions at the time: the Florida Current, or Gulf Stream. That

current had made itself felt when the three ships crossed it going west in the

first days of April, but now, at a cape north of Lake Worth Inlet, which Juan

Ponce named Cabo de las Corrientes (Cape of the Currents), it faced him

head-on and with such force that his ships were propelled backward even

though they had wind abaft the beam. One, the bergantina, was swept out

to deep water. Anchoring north of the cape, Juan Ponce and some of his

men rowed ashore in a longboat to make contact with natives they sighted

on shore. The encounter did not go wel . The native party assaulted the

Spaniards with clubs and arrows, rendering one seaman unconscious and

wounding two others. Herrera states that Juan Ponce had not wished to do

the natives harm but was forced to fight in order to save both his men’s lives

and their boat, oars, and weapons, which their assailants sought to seize.

No cause for the natives’ violence is given in the record, whether it was

provoked by earlier visits of slaving expeditions, or by the natives’ own long

proof

tradition of intertribal warfare, or by simple fear of these strange creatures

from another world.

Regaining his ships, Juan Ponce put in at Jupiter Inlet to take on firewood

and water, only to be attacked again by a larger party of sixty men. This

time he seized a warrior for use as a guide. He would remain anchored in

the river until rejoined by the bergantina. And somewhere along this river,

which he named La Cruz (The Cross), he planted a quarry-stone cross, in-

scribed, with what words we do not know, in the manner of other Spanish or

Portuguese explorers of the period who erected a stone

patrón

, or standard,

to identify their claims.

Final y navigating the Cape of the Currents by hugging the shore, Alami-

nos navigated southward to Key Biscayne, which Juan Ponce named Santa

Marta, and, on Friday, 13 May, to one of the Keys, possibly Key Largo, which

he named Pola, its derivation and meaning unclear. Rounding the Keys as

a body, Juan Ponce named them Los Mártires (Martyrs), “because viewed

from afar the rocks as they rose up seemed like men who are suffering.”4

From Key West he sailed west a short distance and then proceeded north

to explore the reverse side of his “island,” making a Gulf coast landfal , it is

thought, at San Carlos Bay, off the deep mouth of the Caloosahatchee River,

22 · Michael Gannon

and anchoring near the southeast tip of Sanibel Island. There he found fire-

wood and freshwater, careened one of his ships, and had two bel igerent

encounters with natives of the Calusa nation, whose chief, Carlos (as the

Spaniards pronounced and wrote his name), resided on Estero Island. The

Calusa attacked the anchored ships in canoes. One Spaniard and at least

four natives died in these actions, leading Juan Ponce to give Sanibel its

first European name, Matanzas (Massacre). After nine days in the vicinity,

a decision was made to return to Puerto Rico. Accordingly, Alaminos laid a

course that took the ships south-southwest, which caused them, on 21 June,

to come upon waterless keys that Juan Ponce named Las Tortugas (Turtles),

where the crews provisioned the vessels with, among other land and sea spe-

cies, 160 loggerhead turtles. Following a brief reconnaissance of the Cuban

coastline west of Havana, the expedition made for Puerto Rico. Two of the

three ships reached it in mid-October. The third ship, with chief pilot Ala-

minos aboard, Juan Ponce had dispatched into the Lucayans to search again

for the elusive Bimini; that ship would arrive in Añasco Bay four months

later.

In 1514, Juan Ponce sailed to Spain, where he secured a revised royal

asiento naming him

adelantado

(self-financing conqueror and direct rep-

resentative of the king) and governor of the islands of Bimini and Florida.

proof

He was delayed for seven years in executing the contract by the death of his

wife and his need to raise their two young daughters. During that interim,

however, La Florida did not lack for Spanish visitors, including slavers, such

as Pedro de Salazar during a voyage of 1514–16. In 1517, Alaminos, now chief

pilot for Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, took refuge in San Carlos Bay

when Córdoba’s expedition returned eastward from its voyage to Yuca-

tán. And two years later, Alaminos again, this time for Alonzo Alvarez de

Pineda, put into the same bay for its firewood and drinking water during

an expedition that established that Florida was not an island after all but a

peninsula attached to a huge continent. Pineda fixed its western juncture to

the mainland at a feature he named after the Holy Spirit—Río de Espíritu

Santo; this could have been either the Mobile River and Bay, the Mississippi

River, or Vermillion Bay, Louisiana.

His own interest in Florida no doubt requickened by news of Hernán

Cortés’s astonishing discoveries in México, Juan Ponce wrote to the emperor

Carlos V (Carlos I, king of Spain) on 10 February 1521 expressing his inten-

tion to establish a permanent town, a fort, and missions in the Florida he

still thought was an island. On 26 February, he sailed out of Puerto Rico in

two ships loaded down with 200 male and female settlers, parish priests and

First European Contacts · 23

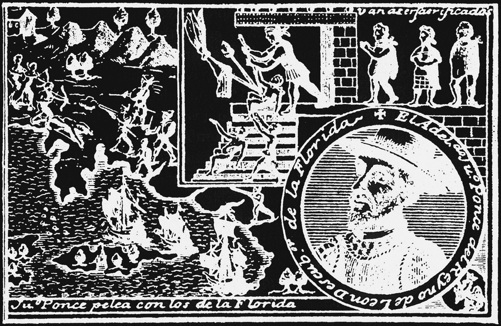

Juan Ponce de León (ca. 1460–1521). The left side of this seventeenth-century engrav-

ing represents Juan Ponce and his expedition of 1521 in combat with the Calusa natives

at Florida’s San Carlos Bay.

missionary friars, horses and domestic animals, seeds, cuttings, and agricul-

proof

tural implements. The site of his landing in Florida is not known with any

certainty, though it has been widely assumed it was in the same San Carlos

Bay region that twice had brought back his former pilot, Alaminos. In any

event, the natives of that site were no more receptive to strangers than were

those Juan Ponce had encountered eight years before. They attacked the

Spaniards as they debarked, as they erected buildings, and as they planted

their crops and tended their cattle. When Juan Ponce himself received a

painful, suppurating arrow wound in his thigh, he ordered the frustrated

and fearful colonists to withdraw to Cuba. There, in July, he died from his

infection.

By the mid-1520s, La Florida was the name given by Spain to the south-

eastern quarter of what is now the United States. Much of its Atlantic coast-

line was probed by slaving expeditions during the decade, and one loqua-

cious captive from Winyah Bay, South Carolina, came into the hands of

Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón, a royal judge in La Española. Persuaded by the

captive, who was given the name Francisco de Chicora, that South Caro-