The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 (2 page)

Read The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 Online

Authors: Gary Ralston

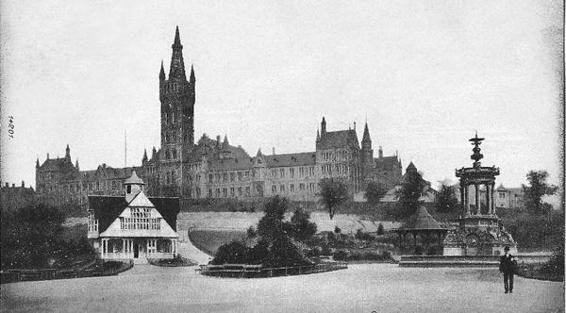

Where it all began: West End Park, later extended and renamed Kelvingrove Park, was the inspiration for the birth of Rangers.

In short and in truth, the story of Rangers is one of the most romantic of any of the greatest sporting clubs formed. It was born uniquely and totally out of a love for the new craze of association football that spread throughout Scotland and England in the 1860s and 1870s. The founding fathers of the club were, in fact, no more than young boys who had come to Glasgow seeking their fortune in business and industry and who, instead, went on to develop an unintentional relationship with fame that keeps their names alive and cherishes the scale of their achievements to this very day. Campbell and McBeath were only 15 years old, Moses McNeil was 16 and his older brother, Peter, was the senior statesman at just 17. Tom Vallance was not there at the conception but he certainly helped in the delivery of the club and was also a mere pup, barely 16 years old. The images and memories of that time are passed down through the yellowed pages of 19th-century newspapers such as the Scottish Athletic Journal, Scottish Umpire, Scottish Sport and Scottish Referee, recalling on-field successes and off-field intrigues. Other, more personal and often harrowing stories come from the vaults and archives of museums and libraries across Britain, including long-hidden horrors of death at sea, insanity and loss of life as a result of business worries, the tag of certified imbecility, a trial for fraud and life in the poorhouse, not to mention a second marriage for one of the founding fathers that was most likely bigamous. Thankfully, there are happier tales to recollect, including a link between a founding father of Rangers and one of the greatest players of all time, Sir Stanley Matthews. There are also fascinating relationships, directly and indirectly, with the growth of the steam trade on the Clyde, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, House of Fraser and a rugby club in Swindon to whom fans who cherish the name of Rangers should be forever indebted.

The pattern of Rangers’ development is weaved inextricably into the rich tapestry that chronicles the growth of Glasgow, where the dominant sporting threads have been coloured blue and green for well over a century. The second city of the empire is as central to the story of the club as the River Clyde was to its earliest trade in tobacco and cotton. In 1765, a little more than 100 years before Rangers staked their first claim to a pitch at Flesher’s Haugh, James Watt was walking deep in thought on Glasgow Green when a vision of an innovative use for steam power came to him and triggered one of the most important developments of the Industrial Revolution. In 1820 there were 21 steam engines operating in the city, yet within a quarter of a century that number had increased to over 300, powering operations in a range of industries including cotton and textiles, chemicals, glass, paper and soap. Later, heavier industries came to dominate, including ironworks, locomotive construction and the aforementioned shipbuilding. In 1831 the first railway arrived in Glasgow, complementing the existing Forth and Clyde and Monklands canals, which had been completed in the early 1790s and were vital to transport raw materials such as coal and ironstone from the bountiful fields of nearby Lanarkshire. On the Clyde, technological developments saw shipbuilding advance at such a pace from the 1820s that within 50 years more than half the British shipbuilding workforce was based on the river, including teenager Peter Campbell, producing half of Britain’s tonnage of shipping – up to 500,000 a year by 1900.

An aerial view of the park Rangers soon made their own: Glasgow Green at the turn of the 20th century.

It was a chaotic recipe for growth that over the course of the century absorbed hundreds of thousands of new inhabitants, the population increasing from 66,000 in 1791 to 658,000 in 1891. By the 1820s, thousands of Scots had been forcibly driven into the clutches of the new industrial age through rural depopulation and Clearances in the Highlands on the back of social reconstruction following the failed Jacobite uprisings. By 1821 the population of Glasgow had risen almost fivefold from 32,000 in 1750, much of it a result of immigration, particularly from Ireland. Many of those who settled in the city in the late 18th century were Irish Presbyterians, drawn by the common ancestry and shared sense of cultural heritage with lowland Scots. They were particularly skilled in weaving and settled in the communities in the east end of the city that traditionally nurtured the trade, such as Bridgeton and Calton. By 1820, it was estimated that up to a third of the area’s weavers were of Irish origin.

In the late 1840s, further Irish immigration as a result of the potato famine also increased the city’s population. The majority of those who arrived in Glasgow as a result of the famine were Catholic, although up to 25 per cent of all those who arrived in Scotland from across the water in the 19th century were Protestant. These were the best and worst of times. In the 1820s and 1830s the average life expectancy for men in Glasgow was just 37, and women fared little better at 40. By the 1880s it had increased, but only slightly, to 42 and 45. There were typhoid epidemics in 1837 and 1847 and Scotland’s first cholera epidemic also hit the city, killing 10,000 people. There were further outbreaks of the deadly disease in 1849 and 1854 when over 7,500 citizens lost their lives. Between the 1830s and the late 1850s, death rates rose to peaks not seen since the 17th century. Even 20 years later there was still a very high infant mortality rate, with up to half of all children born never seeing their fifth birthday. As late as 1906 a school board survey revealed a 14-year-old boy living in a poor area of Glasgow was, on average, four inches shorter than a similar-aged child from the city’s west end. It came as only a perverse crumb of comfort that the extra inches in the city’s poorer quarters would not have been welcomed, given Glasgow’s status at the time as the most overcrowded population centre in Britain.

However, the west end symbolised the self-confidence of Glasgow’s burgeoning mercantile classes and the two Great Exhibitions of 1881 and 1901 in Kelvingrove Park showcased its pride in its reputation as the second city of the Empire. By 1820, the development of the city westwards had reached Blythswood Square, with gridded Georgian terraces extending along Bath Street, St Vincent Street and West George Street. By the 1850s many of these buildings had been commandeered by the city’s business community, which sprang up around George Square and extended up Blythswood Hill as banks, insurance houses and shipping companies expanded in size and influence. As the city’s wealth increased, so was the isolated countryside further west swallowed up from the mid-1800s, particularly with the completion of the Great Western Road and the establishment of the Botanic Gardens on the Kelvinside Estate. The relocation of Glasgow’s University from the High Street to Gilmorehill in 1870 added an academic aura still prevalent today and, all the time, the construction of handsome mansions and elegant townhouses in yellow, pink and red sandstone gathered pace, overseen by architects such as Rennie Mackintosh and Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson around spacious crescents and a plethora of public parks. Glasgow has long claimed more public recreation areas per head of population than any other major European city, giving rise to its proud nickname of the Dear Green Place.

Fittingly, the story of the birth of Rangers straddles both sides of the city. Peter Campbell apart, the founding fathers and their earliest teammates could not be easily tagged as representative of either of the polar opposite communities that confidently sprang up or rose falteringly and with raspish breath in their adopted city. They represented the everyman; neither rich nor poor, privileged nor disadvantaged. They did not come from nor live in the disease-ridden wynds of the Gallowgate, Saltmarket, Calton or High Street, but neither did their addresses declare them as young men of particular wealth or substance. Their homes, like themselves, stood on the fringes of prosperity – close to, but not part of, the affluent west end. To a man, they lived exclusively in the Sandyford area in addresses such as Berkeley Street, Kent Road, Cleveland Street, Elderslie Street and Bentinck Street. They worked, for the most part, in the service industry or white-collar occupations such as drapers, hosiers, clerks and commercial travellers. As Moses and Peter McNeil, William McBeath and Peter Campbell walked through West End Park in March 1872, discussing their desire to form a football club, they may have looked up the hill and been similarly driven to aspire to the lifestyle of those who had just constructed their handsome and spacious homes in the Park district, with panoramic views offering a dramatic sweep across an ever-changing Glasgow cityscape. In time, their fledgling club would climb to lofty peaks in European football, but for many different reasons, personal tragedies among them, none of them would clamber from the foothills towards wealth and prosperity and all would die with their contribution to the history of Rangers virtually unheralded. Until now, their life stories have remained largely unknown and unacknowledged by all but a sympathetic few.

In those heady days their sights were set not on the west, but to the east and the public park of Glasgow Green that had been laid out over 36 acres between 1815 and 1826 by the city fathers, offering a rare opportunity for residents from the claustrophobic lanes and alleyways to sample open spaces. The park provided a vital escape to the people of the east end who existed in appalling conditions, even after the City Improvement Trust had been established in 1866 to clear the slum dwellings and improve squalid living conditions. The park served the recreational needs of the city at the time despite, bizarrely, a bye-law introduced in 1819 prohibiting sporting and leisure pursuits. Cricket and shinty were popular pastimes, as was bowling, and there was even a huge wooden frame gymnasium there. Rowers could be found on the Clyde and the Clydesdale Amateur Rowing Club, formed in 1857, and the Clyde Rowing Club, formed in 1865, catered for eager enthusiasts, including the McNeils, Campbell and Vallance, who had grown up participating in the pastime from a young age on the waters of the Gare Loch.

It came as no surprise that the young friends should decide to form a club of their own, inspired by the likes of Queen’s Park, who were founded on 9 July 1867 when a group of young men met at No. 3 Eglinton Terrace to establish a new club, settling on their club’s name only after rejecting a string of alternatives including Morayshire, The Celts and The Northern, which undoubtedly reflected the Highland roots of their founding sons. Rivals were in such short supply in the early months of Queen’s Park that members were forced to find new and innovative ways to split their numbers into teams on the local recreation ground – at one point smokers played non-smokers. It must have come as some relief when, in August 1868, they finally found opponents named Thistle and rules were quickly agreed between club secretaries. The game was a 20-a-side affair, played over two hours and Queen’s Park won 2–0, setting a pattern for success that would become all too familiar over the subsequent two decades. The Spiders have lifted the Scottish Cup 10 times, which still stands as the most victories in the famous old competition by any club outwith the Old Firm.

Association football had grown increasingly popular in the public schools of England in the first half of the 19th century, although as a sport it had been around for hundreds of years and had been present in China since before the birth of Christ. Rapid advancements were made in football during the Victorian era, not least as a result of the Saturday half-day holiday. It allowed workers who toiled in industry a rare few hours of recreation time beyond the usual Sabbath observance to take part in, or look in on, various leisure activities. On the field, crucial rule changes were adopted soon after the formation of the English FA in October 1863, following a meeting of a dozen clubs from London and the surrounding areas at the Freemasons’ Tavern in Great Queen Street. Until then, there had been little to distinguish the games of football and rugby. By the mid-1860s, however, it had become forbidden for players of the association game to dart forward with the ball in hand as the focus switched to a dribbling game played on the ground. The Scots quickly adapted to new tactics and techniques, developing an early team framework far superior to anything being played south of the border. Queen’s Park were among the first clubs to grasp the benefits of a more structured formation, playing a 2–2–6 formation: two full-backs, two half-backs and six forwards, with two players on the left wing, two on the right and two through the middle. The English clubs persisted with their 1–1–8, but its folly was exposed when the Spiders, playing a short, sharp passing game, saw off top English side Notts County 6–0 at Hampden. Ultimately, it prompted a demand for Scottish players by English clubs that continues to this day.

The FA Cup was instituted in 1871, two years before its Scottish equivalent, and international football also began to develop from the club game, thanks in the first instance to Charles W. Alcock, the administrator, journalist and publisher who would provide the eponymously titled football annual from which Moses McNeil took the Rangers name. It was in November 1870 when, as secretary of the FA, he wrote to the Glasgow Herald suggesting a game between players from both countries. He cajoled: ‘In Scotland, once essentially the land of football, there should still be a spark left of the old fire, and I confidently appeal to Scotsmen to aid to their utmost the efforts of the committee to confer success on what London hopes to be found, an annual trial of skill between the champions of England and Scotland.’3 In total, Alcock arranged four games in London, but the Scots team was plucked from the ranks of Anglos working in the capital, as well as a couple of moonlighters, most notably W.H. Gladstone, the son of the Prime Minister. It came as no great shock when Scotland lost all the games played and the ‘Alcock Internationals’ have no official standing to this day.

Still, sporting history has correctly lauded Alcock as a football visionary and it came as no surprise when the first official international between Scotland and England was played in Glasgow, fittingly on St Andrew’s Day 1872 (football continues to be a sport played, for the most part, from August to May each year, because cricket was the dominant summer pastime in the Victorian era, even in Scotland). Queen’s Park represented the nation that November afternoon after handing over £10 to the West of Scotland Cricket Club for the use of their ground in Hamilton Crescent, Partick, with the promise of a further £10 if takings for the game exceeded £50. In the end, 4,000 people paid £103 to watch the scoreless draw, but there was one notable absentee – the official photographer, who left the ground when players refused to promise they would purchase prints from the game. The overwhelming popularity of the game ensured the fixture’s place in the fledgling football calendar and Scotland soon underlined its supremacy, winning eight and losing only two of the first 12 international matches played against the Auld Enemy.

It was against such a backdrop that Rangers had been formed in 1872, most likely towards the end of March if the earliest account of the club’s history is to be taken as read. And while one or two of the facts are open to question, it carries the strong whiff of authenticity, particularly written so close to the birth itself. One of the leading lights of the earliest Rangers team, William Dunlop, penned the history of the early years for the 1881–82 edition of the Scottish Football Annual under the pseudonym True Blue. Dunlop had joined the club in 1876 (his sister, Mary, would go on to marry Tom Vallance) and was a Scottish Cup finalist against Vale of Leven in 1877 and again in 1879; that same year he began a 12-month term as president of the club. In looking back at the game against Callander he recalled of Rangers: ‘Thus ended their first match, played about the latter end of May 1872, some two months after the inauguration of the club.’

The idea for a football club had been discussed by the teenage pioneers during walks in West End Park, nowadays known as Kelvingrove Park, close to the residences and lodging houses of the youngsters. In the 1871 census Peter McNeil, a 16-year-old clerk, lived at No. 17 Cleveland Street with his oldest sister, Elizabeth, 30, and brothers James, 27, Henry, 21, and William, 19. Moses, a trainee clerk, made his way to join his siblings on his arrival in Glasgow, most likely towards the end of 1871, by which time Elizabeth was head of the household that had subsequently moved around the corner to No. 169 Berkeley Street. Peter Campbell, born and raised in Garelochhead, knew the Shandon brothers from childhood and he was also employed near his friends on moving to Glasgow, at the Barclay Curle shipyard at Stobcross Quay. The quartet was completed by William McBeath, an assistant salesman, who had been born in Callander but arrived in Glasgow from Perthshire with his mother, Jane, soon after the death of his father Peter in 1864. The birth of Rangers symbolised a new beginning for William, who lived in the same tenement close in Cleveland Street as the McNeils. His mother died in March 1872 of chronic bronchitis, aged just 53, with her son’s youthful scrawl officially certifying her death.

Dunlop wrote: ‘A friend of ours, and member of the Rangers, certainly not noted for his accurate knowledge of history, used to remark that there were only two incidents in the history of Scotland specially worth remembering. Jeffrey, Brougham and Sydney Smith met in an old garret in Edinburgh and as a result of their “crack” determined to found the Edinburgh Review. P. McNeil, W. McBeith [sic], M. McNeil and P. Campbell, as the result of a quiet chat carried on without any attempt at brilliancy in the West End Park, determined to found the Rangers FC. These old Rangers had been exercised: in fact, their feelings had been wrought upon, on seeing matches between the Queen’s Park, the Vale (of Leven), and 3rd L.R.V. (Third Lanark). Viewing the interesting and exciting points of the game, even then brilliantly elucidated by the Queen’s Park, had given rise to the itching toe, which could only be relieved by procuring a ball and bestowing upon it an unlimited amount of abuse.’ Friends, particularly those with a Gareloch connection, were rounded up, Harry McNeil and three chums from Queen’s Park agreed to second and soon Rangers were off and running (most of them in their civvies) at Flesher’s Haugh. To be fair, Dunlop freely admitted that the game against Callander was considered a ‘terrible’ spectacle and poor McBeath was so exhausted by his efforts ‘he was laid up for a week,’ although he was named Man of the Match. Nevertheless, inspired and motivated by that first encounter, office bearers were quickly elected and further games arranged.