The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 (5 page)

Read The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 Online

Authors: Gary Ralston

The memorial at Garelochhead Parish Church to John McDonald of Belmore, credited with gifting the first football to Rangers. He was also an early patron of the Clydesdale Harriers, who had close links with the Kinning Park club. The inscription at the base of the monument reads: ‘This cross was erected by the earliest and most intimate friends of John McDonald of Belmore and Torlochan in affectionate remembrance of his many excellent qualities and the noble example of his manly and blameless life. He died at St Leonard’s Windsor, 17th June 1891, aged 40 years, and rests in Clewer Churchyard.’

A 12ft tall Celtic cross still stands in honour of John McDonald junior at Garelochhead Parish Church. He lived long enough to see the club flourish from birth into one of renown but he did not survive into old age and died, after complications arising from flu, in June 1891, aged just 40.

The influence of Stewart and McDonald on the early years of Rangers was more than just an accidental donation of the club’s first football and it is entirely reasonable to conclude that it was through the relationship with the McDonalds that Rangers also secured the support from their business partners, the Stewarts. John Stevenson Stewart was another notable patron of the club and was listed as honorary president of Rangers in the Scottish Football Annuals across various seasons between 1878–85. Born in 1862, he was still a teenager at the time, but would no doubt have been encouraged by his father, Alexander Bannatyne Stewart, to take an active role in public life and choose an association with the Light Blues, perhaps on the back of the growing reputation of the club as a result of their appearance in the 1877 Scottish Cup Final. The title passed to his younger brother Ninian at the Rangers annual meeting in May 1885 and he also gave good service. Certainly, it would not have harmed the reputation of the club to be so closely associated with two of the leading business figures in the city at the time.

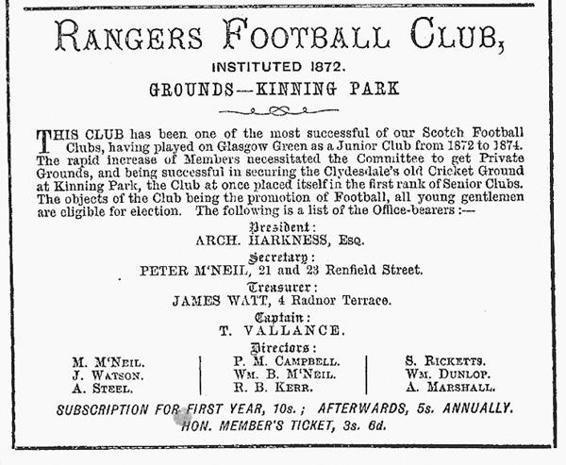

The Scottish Football Annual of 1878–79 was in no doubt about when Rangers were formed, as it announced that the Light Blues had been a junior club on Glasgow Green between 1872–74.

Their father Alexander, born in 1836, had a residence in Langside on Glasgow’s south side known as Rawcliffe, as well as a country retreat, Ascog House on the Isle of Bute, and was a man of substantial means. He died in the Midland Hotel in London during a trip to the capital in 1880 and left an estate worth a staggering £350,000. Alexander had become a partner in the family firm in 1866, six years after the death of his father, and while the business continued to prosper under his command he also had a strong charitable nature. For example, the Robertson-Stewart Hospital in Rothesay was established and supported financially by the family, while the local parish church also benefitted from his largesse. Alexander was a financial backer of the construction of the aquarium and esplanade in the seaside town and many other good causes locally received substantial donations. Indeed, Rangers opened their season in 1879–80 with a game on a public park in Rothesay to raise funds for charities on the Isle of Bute, undoubtedly at the request of John Stevenson Stewart and his father. The Light Blues lost the game 1–0 against Queen’s Park. Clearly, even in those days, charity never extended onto the field of play.

Moses McNeil

There are still those of a certain vintage around today who can remember Moses McNeil living out his latter years in the village of Rosneath on his beloved Clyde peninsula, where he was born on 29 October 1855. He lived modestly for much of the final part of his life before his death from heart disease at the age of 82 on 9 April 1938 at Townend Hospital in Dumbarton. The house he shared latterly with his sister Isabella, Craig Cottage, is still standing, tucked up off the main road leading into the village, away from prying eyes. It is somehow fitting because this giant of Scottish football appeared to withdraw gradually in his latter years from all he had helped create, including Rangers. Even in death, Moses continues to play hide and seek with those keen to acknowledge the enormous role he played in establishing Rangers as a club of stature and also pay tribute to the former Scottish international for his contribution to the game in general. He is buried in the nearby Rosneath graveyard, for sure – his death notice in the Glasgow Herald and records at Cardross Cemetery confirm it – but only recently has the paperwork from the time been uncovered to confirm his interment in a double plot with Isabella and her husband, former sea captain Duncan Gray, and the McNeils’s eldest sister, Elizabeth. As the last of his family line, it is unsurprising that the name of Moses is missing from the gravestone under which he lies. For decades he has given Rangers historians the slip, in the same way he dashed past opposition defences in the 1870s and 1880s as a will-o’-the-wisp left-winger.

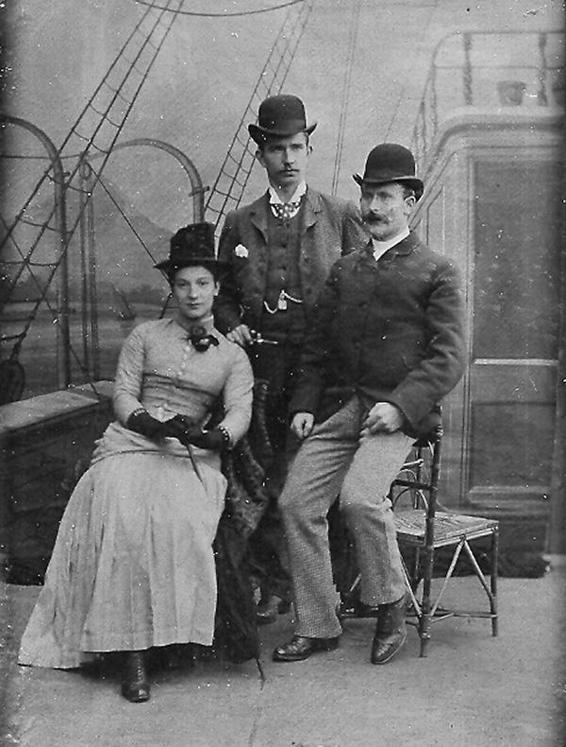

A couple of miles beyond Rosneath, in the village of Kilcreggan, Ian and Ronnie MacGrowther potter around the boatyard they own and which has provided them with a living for more years than they care to remember. The sheds in which they work may be beginning to show signs of age, but the recollections of the brothers from yesteryear in the community in which they were born and raised remain as sharp and mischievous as ever. If Ronnie, born in 1932, closes his eyes he can still picture Moses McNeil, a small man with a navy blue suit and walking stick and very rarely without his bowler hat. ‘He always looked respectable, but I don’t think there was a lot of money around,’ he recalled. ‘A lot of people in the community didn’t know about his connection with Rangers, but my father did. Moses was a nice old man, but he could also be a wee bit prickly on occasions.’ Another former neighbour recalls Moses leaving for Glasgow once a month, they believed to pick up a pension from Rangers. More often than not, there was a spring in his step, a glint in his eye and a slight slur in his speech by the time he returned home much later in the day.

Moses McNeil (right) in a family snapshot – the bowler hat was to remain a feature throughout his life.

Moses, like most of the children of John and Jean McNeil, was raised in a world of wealth and privilege which, unfortunately, was not their own. John McNeil was born in Comrie, Perthshire, in 1809, the son of a farmer, also named John, and mother Catherine Drummond. He came to Glasgow in the early part of the 19th century where he met Jean Loudon Bain, born in around 1815, the daughter of Henry Bain, a grocer and general merchant from Downpatrick in Ireland. They married in Glasgow on 31 December 1839 and although little is known about their early years, religion was clearly important in their lives judging by the grand standing of the minister who conducted their wedding service. The very reverend Duncan McFarlan had been named principal of Glasgow University in 1823 and minister for Glasgow Cathedral in 1824. At the time of the marriage of John and Jean, he had already been Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1819, and was appointed for his second spell in 1843.

According to census records of 1841, John was a gardener at rural Hogganfield Farm, in the north-east of the fledgling city, which only expanded to swallow well-known districts of today such as Anderston, Bridgeton, North Kelvinside and the Gorbals into its boundaries as late as 1846. The young couple’s joy continued when daughter Elizabeth was born the year after they wed and they remained in Glasgow until 1842, celebrating the birth of their first son, John junior. In total, the couple had 11 children, including footballers Moses, Henry, William and Peter, but two boys did not survive infancy, a sad but all too common aspect of childhood at the time.

By the time second son James was born in 1843 the family were living in Rhu and had begun a relationship with the Gareloch that would continue until the death of Moses almost a century later. John, who was now a master gardener, had accepted an offer of employment from John Honeyman at Belmore House near Shandon, on the east side of the Gare Loch now occupied by the Faslane Naval Base. The house, which still stands, had been built to modest dimensions in around 1830 by a local fishing family, the MacFarlanes, but Honeyman, showing an eye for architectural design that would later earn his son his fame and fortune, subsequently bought the house and set about remodelling it, as John took control of its sizeable gardens and brought to fruition his own landscape design skills and vision.

Belmore House, birthplace of Moses McNeil and where his father John lived with his family and worked as a master gardener under the Honeymans and McDonalds. It is now part of the Faslane Naval base.

Honeyman was a corn merchant with a principal residence off Glasgow Green, but had bought Belmore as a weekend and summer retreat. The new steamer routes from Glasgow to the coast and, from 1857, the introduction of the railway to the nearby town of Helensburgh, had made the area more easily accessible for the growing business class. Finance was clearly not an issue for Honeyman, with no expense spared on Belmore. The education of his son, John junior, was also the very best. He boarded at Merchiston Castle in Edinburgh and attended Glasgow University, before setting up an architectural practice in the city in 1854. Honeyman junior joined forces with another designer, John Keppie, in 1888 and within 12 months a young, up-and-coming architect joined the firm’s offices at No. 140 Bath Street in Glasgow city centre – Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

Back at Belmore, the McNeil family continued to expand with the birth of Alexander in 1845, Henry in 1848 and Isabella Honeyman McNeil in 1850 – the latter named in honour of the wife of John’s employer. William McNeil was born in 1852, followed by Peter in 1854 and, finally, in 1855, Moses. Not only was the family of John and Jean growing, so too was the community in which they were living as Glasgow’s new, prosperous, middle classes sought a release from the city and the smog by building second homes on the coast, in towns and villages such as Shandon, Garelochhead, Rhu, Rosneath and Kilcreggan.

In 1856, Belmore House was sold to the McDonalds, that family of impeccable merchant class. By 1871 John, Jean and Moses, then 14, had moved across the Gare Loch to a cottage named Flower Bank, which still stands today above Rosneath. It is possible that John was still in employment at Belmore as it was an easy commute across the loch to the pier at Shandon. The gardens in which John worked no longer stand in their past glory. At their peak, the grounds extended to 33 acres. The house left the McDonald family in 1919 and was sold on again in 1926 to biscuit manufacturer George McFarlane, before eventually passing into government control following his death in 1938. Faslane was developed as a military port from 1942, a role it continues to fill to this day, albeit controversially, as the home of the UK’s Trident nuclear defence programme.