The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 (3 page)

Read The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 Online

Authors: Gary Ralston

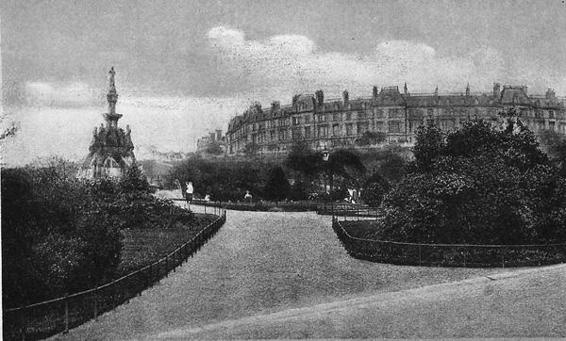

Once upon a dream: Few would have thought a walk along these paths in West End Park would result in the birth of one of the world’s greatest football clubs.

Soon, the youthful Rangers team were the most popular draw on Glasgow Green, courtesy of their exuberant, energetic and winning brand of football. Their earliest fans would undoubtedly have included the residents of the east end of the city, many of them Irish Catholic immigrants, who would subsequently flock to watch Celtic when they were formed 15 years later. Is that not a thought to ponder? There are no direct links between the Rangers of 1872 and now, save the famous name. However, if you look closely you can still connect in the 21st century with the spirit of the McNeils, McBeath and Campbell in the attitudes and outlook of present-day Rangers such as Walter Smith and Ally McCoist. For the most part, the ghostly whispers of the founding fathers of yesteryear are but breezes blowing on the wind, from Flesher’s Haugh up and over the city centre to Great Western Road and Burnbank, swirling across the Clyde to Kinning Park before moving on towards Copland Road, the site of the first Ibrox Park. This early year history is an attempt to present the formation of a great football club against the backdrop of almighty social change in industrialised Glasgow. Rangers survived and prospered, but not all those teenagers who took it upon themselves in the spring of 1872 to form their very own club would, unfortunately, be able to say the same.

The Birth of the Blues

Journalist John Allan may have had the clasp of a loyal Ranger, as Bill Struth once noted, but the strength of his grip on historical reality has always been a bone of contention to many among the Light Blues’ legions. Allan was a former editor of the Daily Record and wrote the three most authoritative tomes on the club he had followed since his childhood in Kinning Park, where he was born in 1879. These days, with the aid of hindsight, The Story of the Rangers, Eleven Great Years and 18 Eventful Years, which cover much of the club’s story until 1951, read like romanticised works of fiction from the empire of Mills and Boon, not Wilton and Struth. Nevertheless, they still carry significant weight, although in relation to the year that should be acknowledged as the birth of the club, The Story of the Rangers does not appear to be accurate.

Even in the 21st century, there are journalists from a bygone era who still recall Allan, who died in April 1953, less than 24 hours after attending his beloved Ibrox for the last time for a Scottish Cup semi-final replay between Aberdeen and Third Lanark. He wrote under the pen name of ‘Brigadier’ -– literally too, for he refused to use a typewriter and filed all his copy via sports desk copy takers from notes on which his pencilled scrawl was illegible to all but himself. He joined the Daily Record as a sportswriter at the turn of the 20th century, although he also contributed a weekly column in the Athletic News and Sporting Chronicle under the name Jonathan Oldbuck.

Allan was renowned for his photographic memory, his patience – and his love of Rangers. The legendary Willie Gallagher, who wrote for decades as Waverley in the pages of the Record, noted that his colleague’s ‘admiration for Rangers was not permitted to interfere with his written views. These were completely unprejudiced and at times he was the Ibrox team’s severest critic.’1 Others, politely, declined to agree. In his book 100 Years of Scottish Sport, written for the Record when he rode side saddle with Alex Cameron as two of the country’s foremost tabloid tale gatherers, Rodger Baillie dusted down the archives to recall the famous 1928 Scottish Cup Final, which Rangers won 4–0. Unsurprisingly, it is remembered as one of the most significant victories in the history of the club as it was the first time the Light Blues had lifted the old trophy in 25 years. Baillie wrote: ‘“Brigadier” was in the Rangers dressing room at the end. It was the nom de plume of John Allan, who was later to have a spell as the editor of the paper. Other executives of that pre-war era believed he tilted the paper’s coverage too much towards Ibrox. Still, he obtained a series of quotes – unusual in those times when players were seen but rarely heard, as the journalists of the day tended to give maximum space to the views of directors and other officials. “You sunk that penalty like an icicle, man,” I told Davie Meiklejohn. “Icicle!” he said. “Why, I never felt so anxious in all my life. It was the most terrible minute of my football career. I hadn’t time to think what it would have meant if I had missed and I can tell you I was relieved when I saw the ball in the back of the net.’’’2

Allan’s respect for Meiklejohn (who, incidentally, went on to write for the Record) was absolute and that is not surprising as the Govan-born right-half, who also operated in the centre of defence, was an Ibrox giant who played 635 games between 1919 and 1936 and won 12 Championship medals, in addition to 15 caps for Scotland. He was one of the club’s greatest captains and his strength of character was never better illustrated than in that Scottish Cup Final when he stepped up to slot the vital first goal past Celtic ’keeper John Thompson from the spot, opening the floodgates for his team to go on and secure one of their most emphatic Cup Final victories. Nevertheless, Allan’s love of football in general and Rangers in particular did cause unrest on the editorial floor of the Record in the 1930s, as former Record and Scotsman editor Alastair Dunnett admitted. He recalled: ‘John McCall…who became editor of the Sunday Mail, told me once how he had been in charge of the Record on the night when the news broke of King Edward VIII and Mrs Wallis Simpson. He had rushed in with it to John Allan’s room, where the editor was sitting with his cronies, drinking and talking about football. Allan interrupted his discourse to look at the story and hear John McCall saying: ‘This is very important Mr Allan. It must be front page.’ Allan looked over the pages briefly, puffed his pipe and handed the pages back, saying: “Aye. Two columns down the page.” And turned to his visitors with “…as I was saying, Davie Meiklejohn is always at his best when he’s in defence…” This was a man who knew little in life except football and he was a rabid Rangers supporter, which did not do the paper any good at all.’3

Allan’s influence stretched beyond the written page to the very corridors of power at Ibrox itself, where he was recognised as a confidant of Struth in particular. The legendary Rangers boss was effusive in his praise in an obituary for Allan that appeared under his byline in the Rangers’ Supporters Association Annual of 1954, his last year as Ibrox boss. In all likelihood, it would have been written by Allan’s nephew Willie Allison, who succeeded the man he affectionately referred to as ‘Muncle’ as club historian and public relations official. Struth recalled of Allan: ‘I still see him walk into my room with the smile of the kindly heart and the clasp of a loyal Ranger. He knew many of my secrets. They were sacred to him. No confidence was ever in danger when given to John. Our success was his success, yet in his role of critic he was a forthright, honest chronicler who sought no favours and gave none in the line of duty.’ Struth added: ‘I have known him to leave his office after many hours of exacting work in putting away his morning paper, slip quietly into his home and pen the deeds of our great teams of the past until roused from his labours by the dawn breaking in on his thoughts. A few hours sleep and he was back at his desk. So brilliant a pen as his could have told an absorbing story without the necessity of detail. But as he said to me: “Without the facts to prove the greatness of the club, my task would be incomplete.” It meant days of research – yes, months if measured in the hours he spent among his unique record books and in the old files that took him back to the beginning of the game.’4

There’s the rub. Allan may have boasted files that went back to the beginning of the game, but it appears his records relating to the rise of Rangers were 12 months out. He insisted the birth of the club came in 1873, a year still celebrated on the intricate mosaics on either side of the Ibrox Main Stand (opened in 1929) and a date which the club has been happy to accept since the publication of Allan’s The Story of the Rangers in 1923, the first great book on the club’s history. It was published to celebrate its jubilee and opened with: ‘In the summer evenings of 1873 a number of lusty, laughing lads, mere boys some of them, flushed and happy from the exhilaration of a finishing dash with the oars, could be seen hauling their craft ashore on the upper reaches of the River Clyde at Glasgow Green.’ Further evidence for the 1873 inception was provided by Moses McNeil himself, in the only ever newspaper interview with the co-founder which research has uncovered. Significantly, however, his first-person piece was printed in Allan’s own Daily Record in April 1935, 48 hours after Rangers had won the Scottish Cup against Hamilton Accies. The influence of Allan loomed large over the copy, which appeared under McNeil’s byline and a headline stating: ‘When Rangers First Reached the Final.’ McNeil, reminiscing on his career three years before his death at the age of 82, wrote: ‘In the summer of 1873 my brothers Peter and Willie and myself, along with some Gareloch lads, banded together on Glasgow Green with the object of forming a football club.’5

Allan went further and categorically stated in The Story of the Rangers that the club was born from a match played at Flesher’s Haugh on 15 July 1873 between two teams, Argyle and Clyde. He added: ‘These names did not represent organised clubs. The two sides were selected for the purpose of providing a game and names were chosen to give the event some individuality.’ He then goes on to list the names of the players from the two competing teams including, for Argyle, Moses and Peter McNeil, William McBeath, Tom Vallance and Peter Campbell. He continued: ‘It is recorded in a news print of the period that the game was very exciting and ended in a draw.’ Despite extensive research enquiries, the news print of the period has never been unearthed.

However, that is not to say the match did not take place. If it was played, it was likely the game between Argyle and Clyde featured players all attached to Rangers and who were split on geography based on upbringing to give a practice match a sharper edge. Games were not always easy to arrange in the early 1870s and there was fluidity around player movement that seems quaint in comparison to the watertight contracts of the modern era. Moses McNeil, for example, took a spell away from Rangers for four months between October 1875 and February 1876 to represent brother Harry’s Queen’s Park in games against London cracks the Wanderers, while Tom Vallance returned to his home village for the festive holidays and turned out for Garelochhead on 3 January 1882 when a touring Queen’s Park select won 2–0.6 Queen’s Park players regularly played against each other using the flimsiest of defining factors to differentiate between sides (smokers against non-smokers, for example, lightweights against heavyweights and even north against south of Eglinton Toll). Certainly, at least two names in the Clyde line up mentioned by Allan, Rankine and Hill, were associated with Rangers as players. Remember too, Allan also had access to a primary source of information in McNeil himself who, by the early 1920s, stood with Tom Vallance as the only survivor from the club’s formative years. If history is written by winners then McNeil was best placed to occupy the podium from which he could oversee a selective narrative, even if it was arguably as flawed as the memory trying to recollect events from 50 years in the past.

Further evidence which suggests Allan’s ability to recall incidents with historical accuracy was not to be trusted came in ‘Brigadier’s’ obituary of Vallance, which appeared in the Daily Record on 18 February 1935, two days after the death of the club’s former skipper and president from a stroke at the age of 78. Brigadier noted: ‘Tom was in the Rangers team that competed in the English Cup and got to the semi-final, only to be beaten by Aston Villa.’ In actual fact, by that time in 1887 Vallance had long since hung up his boots – his career was compromised by ill-health following a short spell working in the tea plantations of Assam in the early 1880s – and he was at that time focused on building his business career and behind-the-scenes duties at Kinning Park.

It would be mean-spirited to pin the inaccuracy of 1873 solely on Moses McNeil or John Allan, and the club’s date of formation was a source of debate around Ibrox in the early 1920s as its jubilee loomed. A celebratory dinner hosted by chairman Sir John Ure Primrose and attended by the greats of the Scottish game took place at the restaurant Ferguson and Forrester’s on Buchanan Street on 9 April 1923 and received widespread coverage in all newspapers the following day. The Evening Times recorded: ‘There has been some difference of opinion as to the year in which the Rangers Football Club originated, but it has been settled to the satisfaction of the gentlemen who at present control the club that the foundation was laid in 1873.’7

Nevertheless, a stronger body of evidence exists to suggest 1872 was much more probable. Firstly, the Scottish Football Association Annuals, published as early as season 1875–76, carried details of every club operating in the game at that time, with information provided by each club secretary. Rangers, with their background most likely recorded by Peter McNeil, were acknowledged from the very first edition as being instituted in 1872. Their entry in one of the earliest editions of the respected handbook even gives a brief, potted history of that period and states: ‘This club has been one of the most successful of our Scottish football clubs, having played on Glasgow Green as a junior club from 1872 to 1874. The rapid increase of members necessitated the committee to get private grounds and being successful in securing Clydesdale’s old cricket ground at Kinning Park, the club at once placed itself in the first rank of senior clubs.’8

One of the earliest and most respected histories of the British game, published in 1905, also declared 1872 to be the year. Furthermore, the article on ‘The Game in Scotland’, part of a four-volume series Association Football And The Men Who Made It was penned by Robert Livingstone, the former president of the SFA. He wrote: ‘The seed sown by Queen’s Park did not all fall on stony ground, however, for in 1872 there sprang into life two clubs which today stand at the very forefront. These were Rangers and Third Lanark and they were accompanied before the footlights of the world by Vale of Leven, destined for a chequered existence, but a still plucky survival.’9

The official Rangers handbook – known affectionately to generations of Ibrox followers as the Wee Blue Book – was published every year from the turn of the 20th century until the 1980s. From its first edition, Rangers were acknowledged as having been formed in 1872. As late as the edition for season 1920–21, under a page section listing historical data, the club’s birth was given as 1872. Significantly, the section of historical data did not appear in the following year’s edition, or in the handbook published for 1922–23. However, it returned for season 1923–24 when, lo and behold, the club’s birth was listed as 1873. Perhaps surprisingly, no explanation was ever offered by the handbook’s editor – John Allan. A theory has surfaced over the years that Allan was under such pressure to publish a jubilee history that he altered the year of formation to suit his own punishing deadline – and historical ends. Allan certainly appears in a literary rush as he gallops through the very early years of Rangers in his book. Further weight to the claim it was expedient for Allan to overlook 1872 as the year of formation comes from the fact that the earlier date does not even merit a mention at all. Surely Allan, with a reputation for such fastidious research, would have at least attempted to explain, in the first great history of the club, why the formation of 1872 that had been universally recognised up to that point was actually wrong? The fact that Allan failed to devote even a sentence to it suggests he was happy to alter history for purposes that suited himself and the club at that time, more than likely related to the constraints of time in organising a programme of events for a milestone few clubs had reached.