The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 (7 page)

Read The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 Online

Authors: Gary Ralston

Homeward bound: the village of Rosneath, where Moses returned to live out his final years with sister, Isabella.

The other side of the argument is that Moses still played an active role in and around the club in the years immediately following his departure from first-team football, even if he chose not to participate politically behind the scenes. He was regular enough for the Rangers ancients and was listed in a team of Kinning Park old boys that took on the Cameronians at Maryhill Barracks in November 1885. He did not play in the ancients against modern game in February 1887 that marked the closure of the old Kinning Park ground, but was pictured in the souvenir photograph taken on the day in a position of prominence in the second row, his trusty cane at hand and that dapper bowler on his head. Brother Harry bowed out of football in September 1888 when a team of Queen’s Park old boys took on a side of Rangers veterans at the exhibition showgrounds at Kelvingrove Park and beat them 2–1. ‘Mosie’ had been tipped to play by the Scottish Umpire but prematurely, although he was not alone in the no-shows. Another McNeil brother, Willie, also failed to trap but the likes of Harry, William ‘Daddy’ Dunlop, George Gillespie, the Vallance brothers and ‘Tuck’ McIntyre kept the sizeable crowd entertained.

Of course, Moses was the source of much of John Allan’s material in his 1923 jubilee history of Rangers and was also quoted at length in the Daily Record of 1935, talking about how he had helped form the club so many years before. He was arguably still in contact with Rangers (if, as his neighbour suspected, he was drawing a pension) or at the very least with people such as Allan, who were close to the Ibrox powerbrokers at the time. However, as life moved on he possibly preferred the pace of a quieter existence, especially after moving to Rosneath around 1930. Few people in the community knew of his connection with Rangers and he was able to live quietly with his sister Isabella at Craig Cottage (before then he had been living in a flat at West Graham Street in the Garnethill district of Glasgow).

Rosneath old cemetery, burial place of Moses McNeil, who rests with sisters Isabella and Elizabeth and his brother-in-law, Captain Duncan Gray.

Moses was certainly company for his sister Isabella, who died in 1935 and whose own life had been touched with terrible sadness. She married master mariner Duncan Gray in 1884, but his life ended at Rosneath in 1907, with his death certificate ominously recording his passing as a result of a gunshot injury to the head. Those still around today with an intimate knowledge of the Grays’ former marital home confirm his suicide.

Moses, the youngest McNeil child and the longest surviving, eventually succumbed to cardiac disease on 9 April 1938 and while someone loved him enough to send a short notice recording his death to the Glasgow Herald and the Evening Times, his name was never added to the gravestone in Rosneath graveyard that includes the inscriptions, faint now after so many decades, in memory of his sisters and brother-in-law. At the time of his death, the sports pages were dominated by the forthcoming Scotland versus England clash at Wembley. Scotland won the match 1–0, courtesy of a goal from Hearts ace Tommy Walker. Rangers also played that afternoon, with a solitary strike from Bob McPhail securing a slender win over Clyde in the League at Ibrox.

The passing of Moses did not merit a mention in the press that week. He was buried on Tuesday 12 April but it was not until six days later that ‘Waverley’ penned an obituary of sorts in the Record. He wrote: ‘A famous player of a long past era in Moses McNeil has also departed. Moses was one of several brothers who helped to form the Rangers clubs [sic] in 1873 and he was the last of the old originals. He played against England in 1880. It is wonderful to think that one who was at the start of the Rangers 65 years ago should have been with us until a few days ago.’4

In recent years, as the final resting place of Moses has become more widely known among the community of Rangers fans, many have made the pilgrimage to Rosneath to pay their respects to easily the best-known name among the club’s founding fathers. A few years ago Rangers awarded Moses one of the first places in the club’s Hall of Fame and now discussions are taking place between the club and the Rosneath Community Council for a more lasting memorial to him in or around the local burial ground. He has given us all the slip for too many years now, left us trailing in his wake like a bemused 19th-century back trying to tackle him on the wing. It is time that Moses McNeil was finally pinned down. For all his achievements, he deserves nothing less than the widest public acknowledgement.

Valiant, Virtuous – and Vale of Leven

It says much for the camaraderie and friendships formed in the early years of Scottish football that reunions of its earliest pioneers were still being held half a century after they had first kicked leather. Old scars were put on display and old scores playfully settled on a day cruise up and down Loch Lomond, held annually throughout the 1920s. The host was former Vale of Leven skipper John Ferguson, a skilful forward who won six caps for Scotland, scoring five goals, and who was an equally proficient athlete and a former winner of the Powderhall Sprint. Ferguson, who worked in the wine and spirit trade in London, had clearly earned handsomely from his career as he laid on the works for his old teammates and rivals from great clubs such as Rangers, Queen’s Park and Third Lanark. The group, typically around 80 strong, ‘their tongues going like “haun guns”,’1 would gather on Balloch Pier at noon before boarding the steamer for a trip to a hotel where a lavish lunch was served. Drink flowed as freely as the anecdotes and on the journey back to Balloch speeches were delivered to the assembled throng. On the last get-together organised by Ferguson, on Saturday 1 September 1928, a year before his death at the age of 81, a familiar old foe stepped forward to speak – former Rangers president Tom Vallance.

Opposite Tarbet, the signal had been given for the vessel, the Prince Edward, to cut its engines in order that the speakers might be more distinctly heard as Vallance, by then in his early seventies, stood up to propose the toast. His jovial address2 to the throng was a touching and heartwarming tribute that underlined just how highly respect and friendship were valued in the very earliest years of the game. Vallance started by saying to those whom had played football that the years spent kicking a ball were the most pleasant of their lives. To loud applause he went on to say he never regretted the decade he committed to Rangers as a player. ‘In fact,’ he revealed, ‘I mentioned this to my good wife, indeed more than once, and she had replied: “You should be playing football yet,” and I did not know whether that was sarcasm or not, but thinking over what she had said, I went to the manager of Rangers and asked if he could find a place for me in the team.’ There was laughter as Vallance admitted Bill Struth had asked him for a fortnight to consider his request and that several months on he was still waiting for his reply. Vallance said it was a great joy to meet with old friends again and added: ‘The other day I read in a spiritualist paper that games were played in heaven and I earnestly hope that is the case, for a heaven without games would have little attraction for me. And if there was football beyond, then assuredly I would get the old Rangers team together and we would challenge the old Vale – and I could tell them the result beforehand; the Vale wouldn’t be on the winning side.’ Vallance reflected on a period soon after their formation during which the youthful nomads of Rangers finally established themselves on the map of the burgeoning Scottish football scene. They were helped to a huge extent by the three games it took to settle the 1877 Scottish Cup Final, and even if they eventually went down to the men from Leven’s shores, they attracted an audience they have never lost since as ‘thousands of the working classes rushed out to the field of battle in their labouring garb, after crossing the workshop gate when the whistle sounded at five o’clock.’3 Rangers have played countless crucial Championship, Cup and European matches in their long and successful history but, even now, few games have been as important to the development of the club as those three encounters, two played on the West of Scotland Cricket Ground at Hamilton Crescent in Partick and the third and decisive head-to-head at the first Hampden Park.

As a fledgling club, effectively a youth team with no ‘home’ to call their own, Rangers were not invited and nor did they apply for membership of the Scottish Football Association in March 1873 when eight clubs came together at the Dewar’s Temperance Hotel in Bridge Street, Glasgow, to form a sporting alliance. Each club – including, of course, the mighty Queen’s Park – contributed £1 towards the purchase of a trophy for a newly established Cup competition – the Scottish Cup. Rangers secured membership in season 1874–75 and in their first Scottish Cup tie, on 12 October 1874, saw off a team called Oxford (from the east end of Glasgow) 2–0 on the Queen’s Park Recreation Ground, with goals from Moses McNeil and David Gibb. In the second round, played at Glasgow Green on 28 November, Rangers drew 0–0 with Dumbarton but lost the replay a fortnight later 1–0 to a controversial winner. The consensus of opinion in an era when goal nets were still a brainwave for the future was that the Dumbarton ‘goal’ had gone over the string bar, rather than under. However, the umpires and referee signalled the goal to stand and Rangers were out of the tournament – for the first time, but certainly not the last – in controversial circumstances.

The backbone of the team in the early years, of course, came from the Gareloch connection – Moses, Willie and Peter McNeil, Peter, James and John Campbell, Alex and Tom Vallance, as well as other friends including William McBeath, James Watson (who became president of the club in 1890), John Yuil and George Phillips. Queen’s Park were regarded as visionaries and pioneers and regularly undertook tours across Scotland to teach the new game to interested participants. However, the great Hampden outfit initially refused to face Rangers in its infancy, citing the new club’s lack of a permanent home as the principal reason. They agreed instead to send their second side, known as the Strollers, but Rangers wanted all or nothing and refused their offer. They wrote again to Queen’s Park in July 1875, and this time the standard-bearers slotted in a game against them on 20 November, with the £28 proceeds from the fixture, a 2-0 victory for the more senior club, distributed to the Bridgeton fire fund. The charity pot had been established to help the eight families left homeless and the 700 workers left idle following a blaze at a spinning mill in Greenhead Street, which was recognised as the biggest ever seen in the city to that date. Amazingly, there were no casualties. An official publication on the history of Queen’s Park, from 1920, was adamant the big boys of the Scottish game were acting not out of malice in refusing a game, but out of concern for the well-being of the youthful club, fearful of crushing its spirit so early in its development.4

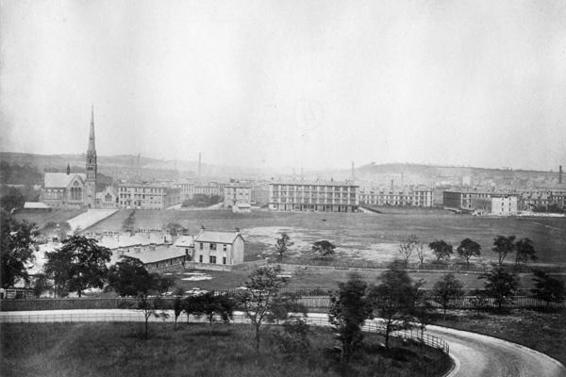

Rangers played at Burnbank for a season between 1875–76. The image above shows the view north from Park Quadrant c.1867 across Burnbank to the new tenements on Great Western Road. The road to the left, next to Lansdowne UP Church, is Park Road, while the houses in the foreground belonged to the Woodside cotton mill and stand on what we know today as Woodlands Road.

The third season of Rangers’ existence had offered glimpses of better to come, with 15 matches played in 1874–75 against sides long since gone, such as Havelock Star, Helensburgh and the 23rd Renfrewshire Rifles Volunteers. Rangers won 12 games, losing only once. The issue of a more permanent base was addressed in time for the start of the 1875–76 season, when the club moved to recreational space at Burnbank, a site on the south side of Great Western Road near St George’s Cross, today bordered by Park Road and Woodlands Road. A move to Shawfield had been briefly considered and then rejected, no doubt as Burnbank was much closer to the homes of the founding fathers around the Sandyford and Charing Cross districts of the city. Initially, Rangers shared the space with Glasgow Accies, the rugby club who were formed in 1866, although they later moved to North Kelvinside. In addition, the Caledonian Cricket Club, who also had a short-lived football team, played on the site, which was later swallowed by developers for tenement housing which still stands today.

Burnbank did its damnedest to stand as an oasis in an increasing desert of red sandstone and was also the home of the First Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers, who were raised in 1859 by the amalgamation of several existing Glasgow corps as a forerunner to the modern territorial army. Among the members of the First Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers and the Glasgow Accies was William Alexander Smith, who founded the Boys Brigade in Glasgow in October 1883. Smith was moved to form his Christian organisation in frustration at his difficulty inspiring members of the Sunday School where he taught at the Mission Hall in nearby North Woodside Road. The youngsters were bored and restless, in stark contrast to the enthusiasm he came across as a young officer among the Volunteers on the Burnbank drill ground every Saturday afternoon. Smith, who was born in 1854, would have been no stranger to Burnbank at the time Rangers were playing there: more than likely he was fermenting his ideas for an organisation that still boasts more than half a million members worldwide at the same time.

Rangers played their first fixture at Burnbank on 11 September 1875 against Vale of Leven, who had quickly established themselves as the second force in the Scottish game behind Queen’s Park. The match finished in a 1–1 draw, but Rangers were beginning to cause a stir. Previously a draw among fans at Glasgow Green, their youthful endeavour and skill at the infant game was starting to attract strong and admiring glances in the west end of the city. A Scottish Athletic Journal rugby columnist, The Lounger, looked back over a decade in 1887 and charted the growth of the fledgling club as he recalled: ‘When I used to go to Burnbank witnessing the rugby games that were played there I always strolled over to the easternmost end of that capacious enclosure to see the Rangers play, and I was never disappointed. They were a much finer team then than they are now. The Vallances were in their prime, P. McNeil was at half-back, Moses – the dashing, clever dribbler of those days – was a forward and P. Campbell and D. Gibb – both dead, I am sorry to say – were also in the team.’5 However, a lengthy run in the Scottish Cup, the principal tournament, was to elude Rangers for a second successive season. In the second round, Rangers defeated Third Lanark 1–0 at Cathkin Park, but their opponents protested that the visitors had kicked-off both halves. The appeal was duly upheld and the game was ordered to be replayed at Burnbank, with Third Lanark winning 2–1. This time it was Rangers’ turn to appeal on the grounds that the opposition keeper wore everyday clothing and could not be distinguished from the crowd, that the winning goal was scored by the hand and that the game had been ended seven minutes early as a result of fans encroaching on the field of play. Their pleas fell on deaf ears. The result stood and Rangers were out.