The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (32 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

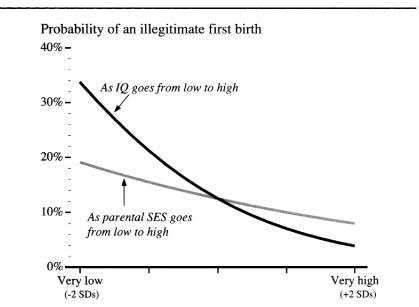

The data from the NLSY generally confirm those reported in the RAND analysis. On the surface, white illegitimacy is associated with socioeconomic status: About 9 percent of babies of women who come from the upper socioeconomic quartile are illegitimate, compared to about 23 percent of the children of women who come from the bottom socioeconomic quartile. But white women of varying status backgrounds

differ in cognitive ability as well. Our standard analysis with IQ, age, and parental SES as independent variables helps to clarify the situation. The dependent variable is whether the first child was born out of wedlock.

27

IQ has a large effect on white illegitimate births independent of the mother’s socioeconomic background

Note: For computing the plot, age and either SES (for the black curve) or IQ (for the gray curve) were set at their mean values.

Higher social status reduces the chances of an illegitimate first baby from about 19 percent for a woman who came from a very low status family to about 8 percent for a woman from a very high status family, given that the woman has average intelligence. Let us compare that 11 percentage point swing with the effect of an equivalent shift in intelligence (given average socioeconomic background ).

28

The odds of having an illegitimate first child drop from 34 percent for a very dull woman to about 4 percent for a very smart woman, a swing of 30 percentage points independent of any effect of socioeconomic status.

Without doubt, the number of well-educated women who are deliberately deciding to have a baby out of wedlock—the name “Murphy Brown” comes to mind—has increased. The Bureau of the Census’s most recent study of fertility of American women revealed that the percentage of never-married women with a bachelor’s degree who had a baby had increased from 3 to 6 percent from 1982 to 1992.

29

But during the same decade, the percentage of never-married women with less than a high school education who had a baby increased from 35 to 48 percent.

30

The role of education continues to be large.

In the NLSY, the statistics contrast even more starkly. Among white women in the NLSY who had a bachelor’s degree (no more, no less) and who had given birth to a child, 99 percent of the babies were born within marriage. In other words, there is virtually no independent role for IQ to play among women in the college sample. It is true that the women in that 1 percent who gave birth out of wedlock were more likely to have the lower test scores—independent of any effect of their socioeconomic backgrounds—but this is of theoretical interest only.

Meanwhile, for white women in the NLSY who had a high school diploma (no more, no less) and had given birth to a child, 13 percent of the children had been born out of wedlock (compared to 1 percent for the college sample). For them, the independent role of IQ was as large as the one for the entire population (as shown in the preceding figure). A high school graduate with an IQ of 70 had a 34 percent probability that the first baby would be born out of wedlock; a high school graduate with an IQ of 130 had less than a 3 percent chance, after extracting the effects of age and socioeconomic background. The independent effect of socioeconomic status was comparatively minor.

We have already noted that family structure at the age of 14 had only modest influence on the chances of getting divorced in the NLSY sample after controlling for IQ and parental SES. Now the question is how the same characteristic affects illegitimacy. Let us consider a white woman of average intelligence and average socioeconomic background. The odds that her first child would be born out of wedlock were:

10 percent if she was living with both biological parents.

18 percent if she was living with a biological parent and a stepparent.

25 percent if she was living with her mother (with or without a live-in boyfriend).

The difference between coming from a traditional family versus anything else was large, with the stepfamily about halfway between the traditional family and the mother-only family.

As we examined the role of family structure with different breakdowns (the permutations of arrangements that can exist are numerous), a few patterns kept recurring. It seemed that girls who were still living with their biological father at age 14 were protected from having their first baby out of wedlock. The girls who had been living with neither biological parent (usually living with adopted parents) were also protected. The worst outcomes seemed conspicuously associated with situations in which the 14-year-old had been living with the biological mother but not the biological father. Here is one such breakdown. The odds that a white woman’s first baby would be born out of wedlock (again assuming average intelligence and socioeconomic background) were:

8 percent if the biological mother, but not the biological father, was absent by age 14.

8 percent if both biological parents were absent at age 14 (mostly adopted children).

10 percent if both biological parents were present at age 14.

23 percent if the biological father was absent by age 14 but not the biological mother.

There is considerable food for thought here, but we refrain from speculation. The main point for our purposes is that family structure is clearly important as a cause of illegitimacy in the next generation.

Did cognitive ability still continue to play an independent role? Yes, for all the different family configurations that we examined. Indeed, the independent effect of IQ was sometimes augmented by taking family structure into account. Consider the case of a young woman at risk, having lived with an unmarried biological mother at age 14. Given average

socioeconomic background and an average IQ, the probability that her first baby would be born out of wedlock was 25 percent. If she had an IQ at the 98th centile (an IQ of 130 or above), the probability plunged to 8 percent. If she had an IQ at the 2d centile (an IQ of 70 or below), the probability soared to 55 percent. High socioeconomic status offered weak protection against illegitimacy once IQ had been taken into account.

31

In the next chapter, we discuss IQ in relation to welfare dependence. Here, we take up a common argument about welfare as a cause of illegitimacy. It is not that low IQ causes women to have illegitimate babies, this argument suggests, but that the combination of poverty and welfare causes women to have illegitimate babies. The logic is that a poor woman who is assured of clothes, shelter, food, and medical care will take fewer precautions to avoid getting pregnant, or, once pregnant, will put less pressure on the baby’s father to marry her, than a woman who is not assured of support. There are two versions of the argument. One sees the welfare system as bribing women to have babies; they get pregnant so they can get a welfare check. The alternative, which we find more plausible, is that the welfare check (and the collateral goods and services that are part of the welfare system)

enables

women to do something that many young women might naturally like to do anyway: bear children.

The controversy about the welfare explanation, in either the “enabling” or “bribe” version, has been intense, with many issues still unresolved.

32

Whichever version is employed, the reason for focusing on the role of poverty is obvious: For affluent young women, the welfare system is obviously irrelevant. They are restrained from having babies out of wedlock by moral considerations or by fear of the social penalties (both of which still exist, though weakened, in middle-class circles), by a concern that the child have a father around the house, and because having a baby would interfere with their plans for the future. In the poorest communities, having a baby out of wedlock is no longer subject to social stigma, nor do moral considerations appear to carry much weight any longer; it is

not

irresponsible to have a child out of wedlock, the argument is more likely to go, because a single young woman can in fact

support the child without the help of a husband.

33

And that brings the welfare system into the picture. For poor young women, the welfare system is highly relevant, easing the short-term economic penalties that might ordinarily restrain their childbearing.

34

The poorer she is, the more attractive the welfare package is and the more likely that she will think herself enabled to have a baby by receiving it.

Given this argument and given that poverty and low IQ are related, let us ask whether the apparent relationship between IQ and illegitimacy is an artifact. Poor women disproportionately have low IQs, and bear a disproportionate number of illegitimate babies. Control for the effects of poverty, says this logic, and the relationship between IQ and illegitimacy will diminish.

Let us see. First, we ask whether the initial condition is true: Is having babies out of wedlock something that is done disproportionately not only by women who come from low socioeconomic backgrounds (a fact which we already have discussed), but women who are literally poor themselves when they reach childbearing age? Even more specifically, are they disproportionately living below the poverty line

before the birth?

We use the italics to emphasize a distinction that we believe offers an important new perspective on single motherhood and poverty. It is one thing to say that single women with babies are disproportionately poor, as we discussed in Chapter 5. That makes sense, because a single woman with a child is often not a viable economic unit. It is quite another thing to say that women who are already poor become mothers. Now we are arguing that there is something about being in the state of poverty itself (after holding the socioeconomic status in which they were raised constant) that makes having a baby without a husband attractive.

To put the question in operational terms: Among NLSY white mothers who were below the poverty line in the year prior to giving birth, what proportion of the babies were born out of wedlock? The answer is 44 percent. Among NLSY white mothers who were anywhere

above

the poverty line in the year before giving birth, what proportion of the babies were born out of wedlock? The answer is only 6 percent. It is a huge difference and makes a prima facie case for those who argue that poverty itself, presumably via the welfare system, is an important cause of illegitimacy.

But now we turn to the rest of the hypothesis: that controlling for poverty will explain away at least some of the apparent relationship between

IQ and illegitimacy. Here is the basic analysis—controlling for IQ, parental SES, and age—restricted to white women who were poor the year before the birth of their babies.

35

Compare the graph below with the one before it and two points about white poor women and illegitimacy are vividly clear. First, the independent importance of intelligence is even greater for poor white women than for white women as a whole. A poor white woman of average socioeconomic background and average IQ has more than a 35 percent chance of an illegitimate first birth. For white women in general, average socioeconomic status and IQ resulted in less than a 15 percent chance. Second, among poor women, the role of socioeconomic background in restraining illegitimacy disappears once the role of IQ is taken into account.

IQ is a more powerful predictor of illegitimacy among poor white women than among white women as a whole

Note: For computing the plot, age and either SES (for the black curve) or IQ (for the gray curve) were set at their mean values.

The results, taken literally, suggest that illegitimacy tends to

rise

among poor women who came from higher socioeconomic background after IQ is taken into account. However, the sample of white women includes too few women who fit all of the conditions (below the poverty line, from a good socioeconomic background, with an illegitimate baby) to make much of this. The more conservative interpretation is that low socioeconomic background, independent of IQ and current poverty itself, does not increase the chances of giving birth out of wedlock among poor white women—in itself a sufficiently provocative finding for sociologists.

36