Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (14 page)

But whatever the mix of truth and fiction in the first two explanations, the third explanation is almost always relevant and almost always ignored. The process described in the previous chapter is driven by a characteristic of cognitive ability that is at once little recognized and essential for understanding how society is evolving: intelligence is fundamentally related to productivity. This relationship holds not only for highly skilled professions but for jobs across the spectrum. The power of the relationship is sufficient to give every business some incentive to use IQ as an important selection criterion.

That in brief is the thesis of the chapter. We begin by reviewing the received wisdom about the links between IQ and success in life, then the evidence specifically linking cognitive ability to job productivity.

“Test scores have a modest correlation with first-year grades and no correlation at all with what you do in the rest of your life,” wrote Derek Bok, then president of Harvard University, in 1985, referring to the SATs that all Harvard applicants take.

1

Bok was poetically correct in ways that a college president understandably wants to emphasize. A 17-year-old who has gotten back a disappointing SAT score should not think that the future is bleak. Perhaps a freshman with an SAT math score of 500 had better not have his heart set on being a mathematician, but if instead he wants to run his own business, become a U.S. senator, or make a million dollars, he should not put aside those dreams because some of his friends have higher scores. The link between test scores and those achievements is dwarfed by the totality of other characteristics that he brings to his life, and that’s the fact that individuals should remember when they look at their test scores. Bok was correct in that, for practical purposes, the futures of most of the 18-year-olds that he was addressing are open to most of the possibilities that attract them.

President Bok was also technically correct about the students at his own university. If one were to assemble the SATs of the incoming freshmen at Harvard and twenty years later match those scores against some quantitative measure of professional success, the impact could be modest, for reasons we shall discuss. Indeed, if the measure of success was the most obvious one, cash income, then the relationship between IQ and success among Harvard graduates could be less than modest; it could be nil or even negative.

2

Finally, President Bok could assert that test scores were meaningless as predictors of what you do in the rest of your life without fear of contradiction, because he was expressing what “everyone knows” about test scores and success. The received wisdom, promulgated not only in feature stories in the press but codified in landmark Supreme Court decisions, has held that, first of all, the relation between IQ scores and job performance is weak, and, second, whatever weak relationship there is depends not on general intellectual capacity but on the particular mental capacities or skills required by a particular job.

3

There have been several reasons for the broad acceptance of the conclusions President Bok drew. Briefly:

A Primer on the Correlation Coefficient

We have periodically mentioned the “correlation coefficient” without saying much except that it varies from −1 to +1. It is time for a bit more detail, with even more to be found in Appendix 1. As in the case of standard deviations, we urge readers who shy from statistics to take the few minutes required to understand the concept. The nature of “correlation” will be increasingly important as we go along.

A correlation coefficient represents the degree to which one phenomenon is linked to another. Height and weight, for example, have a positive correlation (the taller, the heavier, usually). A positive correlation is one that falls between zero and +1, with +1 being an absolutely reliable, linear relationship. A negative correlation falls between O and −1, with −1 also representing an absolutely reliable, linear relationship, but in the inverse direction. A correlation of O means no linear relationship whatsoever.

4A crucial point to keep in mind about correlation coefficients, now and throughout the rest of the book, is that correlations in the social sciences are seldom much higher than .5 (or lower than −.5) and often much weaker—because social events are imprecisely measured and are usually affected by variables besides the ones that happened to be included in any particular body of data. A correlation of .2 can nevertheless be “big” for many social science topics. In terms of social phenomena, modest correlations can produce large aggregate effects. Witness the prosperity of casinos despite the statistically modest edge they hold over their customers.

Moderate correlations mean many exceptions.

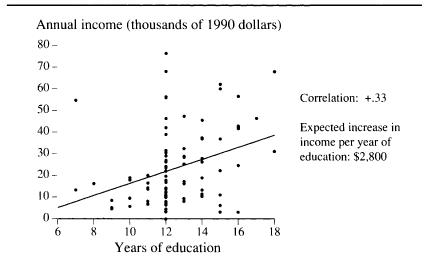

We all know people who do not seem all that smart but who handle their jobs much more effectively than colleagues who probably have more raw intelligence. The correlations between IQ and various job-related measures are generally in the .2 to .6 range. Throughout the rest of the book, keep the following figure in mind, for it is what a highly significant correlation in the social sciences looks like. The figure uses actual data from a randomly selected 1 percent of a nationally representative sample, using two variables that are universally acknowledged to have a large and socially important relationship, income and education, with the line showing the expected change in income for each increment in years of education.

5

For this sample, the correlation was a statistically significant .33, and the expected value of an additional year of education was an additional $2,800 in family income—a major substantive increase. Yet look at how

numerous are the exceptions; note especially how people with twelfth-grade educations are spread out all along the income continuum.

For virtually every topic we will be discussing throughout the rest of the book, a plot of the raw data would reveal as many or more exceptions to the general statistical relationship, and this must always be remembered in trying to translate the general rule to individuals.

The variation among individuals that lies behind a significant correlation coefficient

The exceptions associated with modest correlations mean that a wide range of IQ scores can be observed in almost any job, including complex jobs such as engineer or physician, a fact that provides President Bok and other critics of the importance of IQ with an abundant supply of exceptions to any general relationship. The exceptions do not invalidate the importance of a statistically significant correlation.

Restriction of range.

In any particular job setting, there is a restricted range of cognitive ability, and the relationship between IQ scores and job performance is probably very weak

in that setting.

Forget about IQ for a moment and think about weight as a qualification for being an offensive tackle in the National Football League. The All-Pro probably is not the heaviest player. On the other hand, the lightest tackle in the league weighs about 250 pounds. That is what we mean by restriction of range. In terms of correlation coefficients, if we were to rate the performance

of every NFL offensive tackle and then correlate those ratings with their weights, the result would probably be a correlation near zero. Should we then approach the head coaches of the NFL and recommend that they try out a superbly talented 150-pound athlete at offensive tackle? The answer is no. We would be right in concluding that performance does not correlate much with weight among NFL tackles, whose weights range upward from around 250, but not about the correlation in the general population. Imagine a sample of ordinary people drawn from the general population and inserted into an offensive line. The correlation between the performance of these people as tackles in football games and their weights would be large indeed. The difference between these two correlations—one for the actual tackles in the NFL and the other a hypothetical one for people at large—illustrates the impact of restriction of range on correlation coefficients.

6

Confusion between a credential and a correlation.

Would it be silly to require someone to have a minimum score on an IQ test to get a license as a barber? Yes. Is it nonetheless possible that IQ scores are correlated with barbering skills? Yes. Later in the chapter, we discuss the economic pros and cons of using a weakly correlated score as a credential for hiring, but here we note simply that some people confuse a well-founded opposition to credentialing with a less well-founded denial that IQ correlates with job performance.

7

The weaknesses of individual studies.

Until the last decade, even the experts had reason to think that the relationship must be negligible. Scattered across journals, books, technical reports, conference proceedings, and the records of numberless personnel departments were thousands of samples of workers for whom there were two measurements: a cognitive ability test score of some sort and an estimate of proficiency or productivity of some sort. Hundreds of such findings were published, but every aspect of this literature confounded any attempt to draw general conclusions. The samples were usually small, the measures of performance and of worker characteristics varied and were more or less unreliable and invalid, and the ranges were restricted for both the test score and the performance measure. This fragmented literature seemed to support the received wisdom: Tests were often barely predictive of worker performance and different jobs seemed to call for different predictors. And yet millions of people are hired for jobs every year in competition with other applicants. Employers make those millions

of choices by trying to guess which will be the best worker. What then is a fair way for the employer to make those hiring decisions?

Since 1971, the answer to that question has been governed by a landmark Supreme Court decision,

Griggs

v.

Duke Power Co.

8

The Court held that any job requirement, including a minimum cutoff score on a mental test, must have a “manifest relationship to the employment in question” and that it was up to the employer to prove that it did.

9

In practice, this evolved into a doctrine: Employment tests must focus on the skills that are specifically needed to perform the job in question.

10

An applicant for a job as a mechanic should be judged on how well he does on a mechanical aptitude test, while an applicant for a job as a clerk should be judged on tests measuring clerical skills, and so forth. So decreed the Supreme Court, and why not? In addition to the expert testimony before the Court favoring it, it seemed to make good common sense.

The problem is that common sense turned out to be wrong. In the last decade, the received wisdom has been repudiated by research and by common agreement of the leading contemporary scholars.

11

The most comprehensive modern surveys of the use of tests for hiring, promotion, and licensing, in civilian, military, private, and government occupations, repeatedly point to three conclusions about worker performance, as follows.

- Job training and job performance in many common occupations are well predicted by any broadly based test of intelligence, as compared to narrower tests more specifically targeted to the routines of the job. As a corollary: Narrower tests that predict well do so largely because they happen themselves to be correlated with tests of general cognitive ability.

- Mental tests predict job performance largely via their loading on

g. - The correlations between tested intelligence and job performance or training are higher than had been estimated prior to the 1980s. They are high enough to have economic consequences.

We state these conclusions qualitatively rather than quantitatively so as to span the range of expert opinion. Whereas experts in employee selection accept the existence of the relationship between cognitive ability and job performance, they often disagree with each other’s numerical conclusions. Our qualitative characterizations should be acceptable to those who tend to minimize the economic importance of general cognitive ability and to those at the other end of the range.

12

Why has expert opinion shifted? The answer lies in a powerful method of statistical analysis that was developing during the 1970s and came of age in the 1980s. Known as meta-analysis, it combines the results from many separate studies and extracts broad and stable conclusions.

13

In the case of job performance, it was able to combine the results from hundreds of studies. Experts had long known that the small samples and the varying validities, reliabilities, and restrictions of range in such studies were responsible to some extent for the low, negligible, or unstable correlations. What few realized was how different the picture would look when these sources of error and underestimation were taken into account through meta-analysis.

14

Taken individually, the studies said little that could be trusted or generalized; properly pooled, they were full of gold. The leaders in this effort—psychologists John Hunter and Frank Schmidt have been the most prominent—launched a new epoch in understanding the link between individual traits and economic productivity.