The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (33 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

Our main purpose has been to demonstrate that low intelligence is an important independent cause of illegitimacy, and to do so we have considered the role of poverty. In reality, however, we have also opened up many new avenues of inquiry that we cannot fully pursue without writing an entire book on this subject alone. For example, the results raise many questions to be asked about the “culture of poverty” argument. To the extent that a culture of poverty is at work, transmitting dysfunctional values from one generation to the next, it seems paradoxical that low socioeconomic background does not foster illegitimacy once poverty in the year prior to birth is brought into the picture.

But the main task posed by these results is to fill in the reason for that extremely strong relationship between low IQ and illegitimacy within the population of poor white women. The possibilities bear directly on some of the core issues in the social policy debate. For example, many people have argued that the welfare system cannot really be a cause of illegitimacy, because, in objective terms, the welfare system is a bad deal. It provides only enough to squeak by, it can easily trap young women into long-term dependence, and even poor young women would be much better off by completing their education and getting a job rather than having a baby and going on welfare. The results we have presented can be interpreted as saying that the welfare system may be a bad deal, but it takes foresight and intelligence to understand why. For women without foresight and intelligence, it may seem to be a good deal. Hence poor young women who are bright tend not to have illegitimate babies nearly as often as poor young women who are dull.

Another possibility fits in with those who argue that the best preventative for illegitimacy is better opportunities. It is not the welfare system that is at fault but the lack of other avenues. Poor young women who are bright are getting scholarships, or otherwise having positive incentives

offered to them, and they accordingly defer childbearing. Poor young women who are dull do not get such opportunities; they have nothing else to do, and so have a baby. The goal should be to provide them too with other ways of seeing their futures.

Both of these explanations are stated as hypotheses that we hope others will explore. Those explorations will have to incorporate our central finding, however: Cognitive ability in itself is an important factor in illegitimacy, and the dynamics for understanding illegitimacy—and dealing with it through policy—must take that strong link into account.

Our goal has been to sharpen understanding of the much-lamented breakdown of the American family. The American family has been as battered in the latter decades of the twentieth century as the public rhetoric would have it, but the damage as measured in terms of divorce and illegitimacy has been far more selective than we hear. By way of summary, let us consider the children of the white NLSY mothers in the top quartile of cognitive ability (Classes I and II) versus those in the bottom quartile (Classes IV and V):

The percentage of households with children that consist of a married couple:

87 percent in the top quartile of IQ, 70 percent in the bottom quartile.

The percentage of households with children that have experienced divorce:

17 percent in the top quartile of IQ, 33 percent in the bottom quartile.

The percentage of children born out of wedlock:

5percent in the top quartile of IQ, 23 percent in the bottom quartile.

The American family may be generally under siege, as people often say. But it is at the bottom of the cognitive ability distribution that its defenses are most visibly crumbling.

Welfare Dependency

People have had reason to assume for many years that welfare mothers are concentrated at the low end of the cognitive ability distribution, if only because they have generally done poorly in school. Beyond that, it makes sense that smarter women can more easily find jobs and resist the temptations of welfare dependency than duller ones, even if they have given birth out of wedlock.

The link is confirmed in the NLSY. Over three-quarters of the white women who were on welfare within a year of the birth of their first child came from the bottom quartile of IQ, compared to 5 percent from the top quartile. When we subdivide welfare recipients into two groups, “temporary” and “chronic,” the link persists, though differently for the two groups.

Among women who received welfare temporarily, low IQ is a powerful risk factor even after the effects of marital status, poverty, age, and socioeconomic background are statistically extracted. For chronic welfare recipiency, the story is more complicated. For practical purposes, white women with above-average cognitive ability or above-average socioeconomic background do not become chronic welfare recipients. Among the restricted sample of low-IQ, low-SES, and relatively uneducated white women who are chronically on welfare, low socioeconomic background is a more powerful predictor than low IQ, even after taking account of whether they were themselves below the poverty line at the time they had their babies.

The analyses provide some support for those who argue that a culture of poverty tends to transmit chronic welfare dependency from one generation to the next. But if a culture of poverty is at work, it seems to have influence primarily among women who are of low intelligence.

A

part from whether it causes increased illegitimacy, welfare has been a prickly topic in the social policy debate since shortly after the core welfare program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC),

was created in the mid-1930s. Originally AFDC was a popular idea. No one in the community was a likelier object of sympathy than the young widow with small children to raise, and AFDC seemed to be a way to help her stay home with her children until they were old enough to begin taking care of her in their turn. And if some of the women going on AFDC had not been widowed but abandoned by no-good husbands, most people thought that they should be helped too, though some people voiced concerns that helping such women undermined marriage.

But hardly anyone had imagined that never-married women would be eligible for AFDC. It came as a distressing surprise to Frances Perkins, the first woman cabinet member and a primary sponsor of the legislation, to find that they were.

1

But not only were they eligible; within a few years after AFDC began, they constituted a large and growing portion of the caseload. This created much of the general public’s antagonism toward AFDC: It wasn’t just the money, it was the principle of the thing. Why should hardworking citizens support immorality?

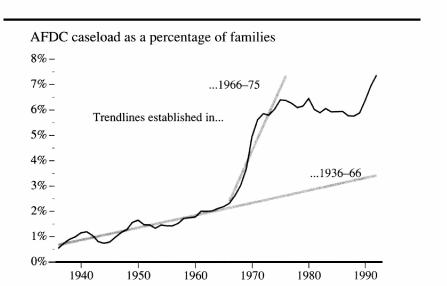

Such complaints about welfare go far back into the 1940s and even the 1930s, but, at least from our perspective in the 1990s, it was much ado about a comparatively small problem, as the next figure shows. After a slow and meandering rise since the end of World War II, the welfare caseload was still less than 2 percent of families when John E Kennedy took office. Then, as with so many other social phenomena, the dynamics abruptly changed in mid-1960s. In a concentrated period from 1966 to 1975, the percentage of American families on welfare nearly tripled. The growth in the caseload then stopped and even declined slightly through the 1980s. Welfare rolls have been rising steeply since 1988, apparently beginning a fourth era. As of 1992, more than 14 million Americans were on welfare.

The welfare revolution

Sources:

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1975, Table H 346-367; annual data published in the Social

Security Bulletin.

The steep rise in the welfare population is obviously not to be explained by intelligence, which did not plummet in the 1960s and 1970s. More fundamental forces were reshaping the social landscape during that time. The surging welfare population is just one outcropping among others summarized in Part II of trouble in American society. In this chapter, the theme will be, as it is elsewhere in the book, that as society changes, some people are especially vulnerable to the changes—in this instance, to events that cause dependence on welfare. We show here that low intelligence increases a white mother’s risk of going on welfare, independent of the other factors that might be expected to explain away the relationship.

It has not been an openly discussed topic, but there are many good reasons for assuming that welfare mothers come mainly from the lower reaches of the distribution of cognitive ability. Women on welfare have less education than women not on welfare, and chronic welfare recipients have less education than nonchronic recipients.

2

Welfare mothers have been estimated to have reading skills that average three to five years below grade level.

3

Poor reading skills and little schooling define populations with lower-than-average IQ, so even without access to IQ tests, it can be deduced that welfare mothers have lower-than-average intelligence. But can it be shown that low IQ has an independent link with welfare itself, after taking account of the less direct links via being poor and being an unwed mother?

4

By a direct link, we mean something like this: The smarter the woman is, the more likely she will be able to find a job, the more likely she will be able to line up other sources of support (from parents or the father of the child), and the more farsighted she is likely to be about the dangers

of going on welfare. Even within the population of women who go on welfare, cognitive ability will vary, and the smarter ones will be better able to get off.

No database until the NLSY has offered the chance to test these hypotheses in detail for a representative population. We begin as usual with a look at the unadorned relationship with cognitive class.

Use of welfare is uncommon but not rare among these white mothers, as the table below shows. Overall, 12 percent of the white mothers in the NLSY received welfare within a year of the birth of their first child; 9 percent had become chronic recipients by our definition of chronic welfare recipients (meaning that they had reported at least five years of welfare income). Overall, 21 percent of white mothers had received assistance from AFDC at some point in their lives.

5

The differences among the cognitive classes are large, with a conspicuously large jump in the rates at the bottom. The proportion of women in Class IV who became chronic welfare recipients is double the rate for Class III, with another big jump for Class V, to 31 percent of all mothers.

| Which White Women Go on Welfare After the Birth of the First Child? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Mothers Who Went on AFDC Within a Year of First Birth | Cognitive Class | Percentage of Mothers Who Became Chronic Welfare Recipients |

| aSample = 17, with no one qualifying as a chronic welfare recipient. Minimum sample reported: 25. | ||

| 1 | I Very bright | a |

| 4 | II Bright | 2 |

| 12 | III Normal | 8 |

| 21 | IV Dull | 17 |

| 55 | V Very dull | 31 |

| 12 | Overall average | 9 |

This result should come as no surprise, given what we already know about the higher rates of illegitimate births in the lower half of the cognitive ability distribution (Chapter 8). Women without husbands are most at risk for going on welfare. We also know that poverty has a strong association with the birth status of the child. In fact, it may be asked

whether we are looking at anything except a reflection of illegitimacy and poverty in these figures. The answer is yes, but a somewhat different “yes” for periodic and for chronic welfare recipiency.

First, we ask of the odds that a woman had received welfare by the end of the first calendar year after the birth of her first child.

6

In all cases, we limit the analysis to white women whose first child was born prior to 1989, so that all have had a sufficient “chance” to go on welfare.

If we want to understand the independent relationship between IQ and welfare, the standard analysis, using just age, IQ, and parental SES, is not going to tell us much. We have to get rid of the confounding effects of being poor and unwed. For that reason, the analysis that yielded the figure below extracted the effects of the marital status of the mother and whether she was below the poverty line in the year before birth, in addition to the usual three variables. The dependent variable is whether the mother received welfare benefits during the year after the birth of her first child. As the black line indicates, cognitive ability predicts going on welfare even after the effects of marital status and poverty have been extracted. This finding is worth thinking about, for it is not intuitively predictable. Presumably much of the impact of low intelligence on being on welfare—the failure to look ahead, to consider consequences, or to get an education—is already captured in the fact that the woman had a baby out of wedlock. Other elements of competence, or lack of it, are captured in the fact that the woman was poor before the baby was born. Yet holding the effects of age, poverty, marital status, and parental SES constant, a white woman with an IQ at the 2d centile had a 47 percent chance of going on welfare, compared to the 8 percent chance facing a white woman at the 98th centile.