The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (34 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

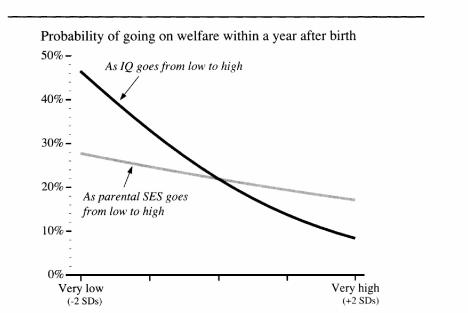

Even after poverty and marital status are taken into account, IQ played a substantial role in determining whether white women go on welfare

Note: For computing the plot, age and either SES (for the black curves) or IQ (for the gray curves) were set at their mean values. Additional independent variables of which the effects have been extracted for the plot: marital status at the time of first birth, and poverty status in the calendar year prior to the first birth.

The socioeconomic background of these mothers was not a statistically significant factor in their going on welfare.

We cannot analyze welfare recipiency among white women with a bachelor’s degree because it was so rare: Of the 102 white mothers with a B.A. (no more, no less) who met the criteria for the sample, 101 had never received any welfare. But we can take a look at the high school sample. For them, low cognitive ability was as decisive as for the entire population of NLSY white mothers. The magnitude of the independent effect of IQ was about the same, and the effect of socioeconomic status was again statistically insignificant. The other variables swept away all of the connections between welfare and social class that seem so evident in everyday life.

Now we focus on a subset of women who go on welfare, the chronic welfare recipients. They constitute a world of their own. In the course of the furious political and scholarly struggle over welfare during the 1980s, two stable and consistent findings emerged, each having different implications: Taking all the women who ever go on welfare, the average

spell lasts only about two years.

7

But among never-married mothers (all races) who had their babies in their teens, the average time on welfare is eight or more years, depending on the sample being investigated.

8

The white women who had met our definition of chronic welfare recipient in the NLSY by the 1990 interview fit this profile to some extent. For example, of the white women who gave birth to an illegitimate baby before they were 19 (that is, they probably got pregnant before they would normally have graduated from high school) and stayed single, 22 percent became chronic welfare recipients by our definition—a high percentage compared to women at large. On the other hand, 22 percent is a long way from 100 percent. Even if we restrict the criteria further so that we are talking about single teenage mothers who were below the poverty line, the probability of becoming a chronic welfare recipient goes up only to 28 percent.

To get an idea of how restricted the population of chronic welfare mothers is, consider the 152 white women in the NLSY who met our definition of a chronic welfare recipient and also had IQ scores. None of them was in Cognitive Class I, and only five were even in Class IL Only five had parents in the top quartile in socioeconomic class. One lone woman of the 152 was from the top quartile in ability

and

from the top quartile in socioeconomic background. White women with above-average cognitive ability or socioeconomic background rarely become chronic welfare recipients.

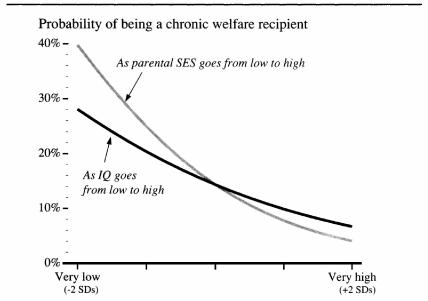

Keeping this tight restriction of range in mind, consider what happens when we repeat the previous analysis (including the extra variables controlling for marital status and poverty at the time of first birth) but this time comparing mothers who became chronic welfare recipients with women who never received any welfare.

9

According to the figure, when it comes to chronic white welfare mothers, the independent effect of the young woman’s socioeconomic background is substantial. Whether it becomes more important than IQ as the figure suggests is doubtful (the corresponding analysis in Appendix 4 says no), but clearly the role of socioeconomic background is different for all welfare recipients and chronic ones. We spent much time exploring this shift in the role of socioeconomic background, to try to pin down what was going on. We will not describe our investigation with its many interesting byways, instead simply reporting where we came out. The answer turns out to hinge on education.

Socioeconomic background and IQ are both important in determining whether white women become chronic welfare recipients

Note: For computing the plot, age and either SES (for the black curves) or IQ (for the gray curves) were set at their mean values. Additional independent variables of which the effects have been extracted for the plot: marital status at the time of first birth, and poverty status in the calendar year prior to the first birth.

White chronic welfare recipients are virtually all women with modest education at best, as set out in the next table. More than half of the chronic welfare recipients had not gotten a high school diploma; only six-tenths of 1 percent had gotten a college education. As in the case of IQ and socioeconomic status, this is a radically unrepresentative sample of white women.

10

It is obviously impossible (as well as unnecessary) to analyze chronic welfare recipiency among college graduates.

The women for whom socioeconomic background was the main risk factor for being chronically on welfare are those who had not finished high school For women with a high school diploma or more, IQ was

more important than socioeconomic status (other things equal) in affecting the probability of becoming a chronic welfare recipient.

11

| Educational Attainment of White Chronic Welfare Recipients | |

|---|---|

| Highest Degree | Percentage |

| Advanced degree | 0 |

| B.A. or B.S. | 1 |

| Associate degree | 3 |

| High school diploma | 42 |

| GED | 16 |

| Less than high school | 38 |

Why? Apparently the women who did not finish high school and had an illegitimate child were selected for low intelligence, especially if they had the child while still in high school.

12

The average IQ of these women was about 91, and analysis tells us that further variation in cognitive ability does not have much power to predict which ones become chronic welfare cases.

13

Instead, for this narrowly screened group of women, family background matters more. Without trying to push the analysis much further, a plausible explanation is that for most white American parents, having a school-aged child go on welfare is highly stigmatizing

to them.

If the daughter of a working-class or middle-class couple gives birth to a baby out of wedlock while still in high school, chances are that her parents will take over support for the new baby rather than let their daughter go on welfare. The parents who do not keep their school-aged daughter off welfare will tend to be those who are not deterred by the stigma or who are themselves too poor to support the new baby. Both sets of parents earn low scores on the socioeconomic status index. Hence what we are observing in the case of chronic welfare recipiency among young women who do not finish high school may reflect parental behavior as much as the young mother’s behavior.

14

Other hypotheses are possible, however. Generally these results provide evidence for those who argue that a culture of poverty transmits chronic welfare dependency from one generation to the next. Our analysis adds that women who are susceptible to this culture are likely to have low intelligence in the first place.

As social scientists often do, we have spent much effort burrowing through analyses that ultimately point to simple conclusions. Here is how a great many parents around America have put it to their daughters: Having a baby without a husband is a dumb thing to do. Going on welfare is an even dumber thing to do, if you can possibly avoid it. And so it would seem to be among the white women in the NLSY. White women who remained childless or had babies within marriage had a mean IQ of 105. Those who had an illegitimate baby but never went on welfare had a mean IQ of 98. Those who went on welfare but did not become chronic recipients had a mean IQ of 94. Those who became chronic welfare recipients had a mean IQ of 92.

15

Altogether, almost a standard deviation separated the IQs of white women who became chronic welfare recipients from those who remained childless or had children within marriage.

In Chapter 8, we demonstrated that a low IQ is a factor in illegitimate births that cannot be explained away by the woman’s socioeconomic background, a broken family, or poverty at the time the child was conceived. In particular, poor women of low intelligence seemed especially likely to have illegitimate babies, which is consistent with the idea that the prospect of welfare looms largest for women who are thinking least clearly about their futures. In this chapter, we have demonstrated that even among women who are poor and even among those who have a baby without a husband, the less intelligent tend to be the ones who use the welfare system.

Two qualifications to this conclusion are that (1) we have no way of knowing whether higher education or higher IQ explains why college graduates do not use welfare—all we know is that welfare is almost unknown among college-educated whites, but that for women with a high school education, intelligence plays a large independent role—and (2) for the low-IQ women without a high school education who become chronic welfare recipients, a low socioeconomic background is a more important predictor than any further influence of cognitive ability.

The remaining issue, which we defer to the discussion of welfare policy in Chapter 22, is how to reconcile two conflicting possibilities, both

of which may have some truth to them: Going on welfare really is a dumb idea, and that is why women who are low in cognitive ability end up there; but also such women have little to take to the job market, and welfare is one of their few appropriate recourses when they have a baby to care for and no husband to help.

Parenting

Everyone agrees, in the abstract and at the extremes, that there is good parenting and poor parenting. This chapter addresses the uncomfortable question: Is the competence of parents at all affected by how intelligent they are?

It has been known for some time that socioeconomic class and parenting are linked, both to disciplinary practices and to the many ways in which the intellectual and emotional development of the child are fostered. On both counts, parents with higher socioeconomic status look better. At the other end of the parenting continuum, neglect and abuse are heavily concentrated in the lower socioeconomic classes.

Whenever an IQ measure has been introduced into studies of parent-child relationships, it has explained away much of the differences that otherwise would have been attributed to education or social class, but the examples are sparse. The NLSY provides an opportunity to fill in a few of the gaps.

With regard to prenatal and infant care, low IQ among the white mothers in the NLSY sample was related to low birth weight, even after controlling for socioeconomic background, poverty, and age of the mother. In the NLSY’s surveys of the home environment, mothers in the top cognitive classes provided, on average, better environments for children than the mothers in the bottom cognitive classes. Socioeconomic background and current poverty also played significant roles, depending on the specific type of measure and the age of the children.

In the NLSY’s measures of child development, low maternal IQ was associated with problematic temperament in the baby and with low scores on an index of “friendliness,” with poor motor and social development of toddlers and with behavioral problems from age 4 on up. Poverty usually had a modest independent role but did not usually diminish the contribution of IQ (which was usually also modest). Predictably, the mothers IQ was also strongly related to the IQ of the child.