The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (29 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

Whatever validity this explanation may have, however, it is unlikely to be the whole story. We will simply observe that self-reported health problems are subject to a variety of biases, especially when the question is so sensitive as one that asks, in effect, “What is your excuse for not looking for a job, young man?” The evidence in the NLSY regarding the seriousness of the ailments, whether a doctor has been consulted, and their duration raises questions about whether the self-reported disability data have the same meaning when reported by (for example) a subject who reports that he was two months out of the labor market because

of a broken leg and another who reports that he has been out of the labor market for five years because of a bad back.

We leave the analysis of labor force participation with a strong case to be made for two points: Cognitive ability is a significant determinant of dropout from the labor force by healthy young men, independent of other plausibly important variables. And the group of men who are out of the labor force because of self-described physical disability tend toward low cognitive ability, independent of the physical demands of their work.

Men who are out of the labor force are in one way or another unavailable for work; unemployed men, in contrast, want work but cannot find it. The distinction is important. The nation’s unemployment statistics are calculated on the basis of people who are looking for work, not on those who are out of the labor force. Being unemployed is transitory, a way station on the road to finding a job or dropping out of the work force. But it is hard to see much difference between unemployment and dropping out in the relationship with intelligence. We begin with the basic breakdown, set out in the following table. The extremes—Classes I and V—differed markedly in the frequency of unemployment lasting a month or more, with Class V experiencing six times the unemployment of Class I. Class IV also had higher unemployment than the upper three-quarters of the IQ distribution.

| Which White Young Men Spent a Month or More Unemployed in 1989? | |

|---|---|

| Cognitive Class | Percentage |

| I Very bright | 2 |

| II Bright | 7 |

| III Normal | 7 |

| IV Dull | 10 |

| V Very dull | 12 |

| Overall average | 7 |

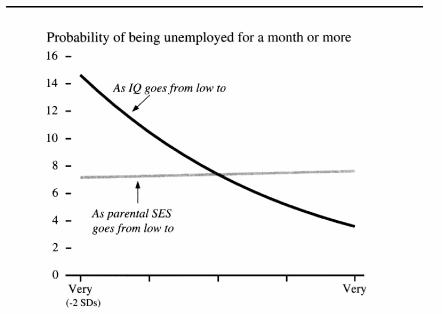

The independent roles of our three basic variables are shown in the figure below. For a man of average age and socioeconomic background, cognitive ability lowered the probability of being unemployed for a month from 15 percent for a man at the 2d centile of IQ to 4 percent for men at the 98th centile. Neither parental SES nor age had an appreciable (or statistically significant) independent effect.

Before looking at the numbers, we would have guessed that cognitive ability would be more important for explaining unemployment among the high school sample than among the college sample. The logic is straightforward: A college degree supplies a credential and sometimes specific job skills that, combined with the college graduate’s greater average level of intelligence, should reduce the independent role of IQ in ways that would not apply as strongly to high school graduates.

8

But this logic is not borne out by the NLSY. Cognitive ability was more important in determining unemployment among college graduates than among the high school sample, although the small sample sizes in this analysis make this conclusion only tentative. Socioeconomic background and age were not independently important in explaining unemployment in the high school or college samples.

High IQ lowers the probability of a month-long spell of unemployment among white men, while socioeconomic background has no effect

Note: For computing the plot, age and either SES (for the black curve) or IQ (for the gray curve) were set at their mean values.

The most basic implication of the analysis is that intelligence and its correlates—maturity, farsightedness, and personal competence—are important in keeping a person employed and in the labor force. Because such qualities are not entirely governed by economic conditions, the question of who is working and who is not cannot be answered just in terms of what jobs are available.

This does not mean we reject the relevance of structural or economic conditions. In bad economic times, we assume, finding a job is harder for the mature and farsighted as well as for the immature and the shortsighted, and it is easier to get discouraged and drop the search. Our goal is to add some leavening to the usual formulation. The state of the economy matters, but so do personal qualities, a point that most economists would probably accept if it were brought to their attention so baldly, but somehow it gets left out of virtually all discussions of unemployment and labor force participation.

As we close this discussion of cognitive ability and labor force behavior, let us be clear about what has and has not been demonstrated. In focusing on those who did drop out of the labor force and those who were unemployed, we do not want to forget that most white males at every level of cognitive ability were in the labor force and working, even at the lowest cognitive levels. Among physically able white males in Class V, the bottom 5 percent of the IQ distribution, comprising men who are intellectually borderline or clinically retarded, seven out of ten were in the labor force for all fifty-two weeks of 1989. Of those who were in the labor force throughout the year, more than eight out of ten experienced not a single week of unemployment.

Condescension toward these men is not in order, nor are glib assumptions that those who are cognitively disadvantaged cannot be productive citizens. The world is statistically tougher for them than for others who are more fortunate, but most of them are overcoming the odds.

Family Matters

Rumors of the death of the traditional family have much truth in them for some parts of white American society—those with low cognitive ability and little education—and much less truth for the college educated and very bright Americans of all educational levels. In this instance, cognitive ability and education appear to play mutually reinforcing but also independent roles.

For marriage, the general rule is that the more intelligent get married at higher rates than the less intelligent. This relationship, which applies across the range of intelligence, is obscured among people with high levels of education because college and graduate school are powerful delayers of marriage.

Divorce has long been more prevalent in the lower socioeconomic and educational brackets, but this turns out to be explained better by cognitive level than by social status. Once the marriage-breaking impact of low intelligence is taken into account, people of higher socioeconomic status are more likely to get divorced than people of lower status.

Illegitimacy, one of the central social problems of the times, is strongly related to intelligence. White women in the bottom 5 percent of the cognitive ability distribution are six times as likely to have an illegitimate first child as those in the top 5 percent. One out of five of the legitimate first babies of women in the bottom 5 percent was conceived prior to marriage, compared to fewer than one out of twenty of the legitimate babies to women in the top 5 percent. Even among young women who have grown up in broken homes and among young women who are poor—both of which foster illegitimacy—low cognitive ability further raises the odds of giving birth illegitimately. Low cognitive ability is a much stronger predisposing factor for illegitimacy than low socioeconomic background.

At lower educational levels, a woman’s intelligence best predicts whether she will bear an illegitimate child. Toward the higher reaches of education, almost no white women are having illegitimate children, whatever their family background or intelligence.

T

he conventional understanding of troubles in the American family has several story lines. The happily married couple where the husband works and the wife stays home with the children is said to be as outmoded as the bustle. Large proportions of young people are staying single. Half the marriages end in divorce. Out-of-wedlock births are soaring.

These features of modern families are usually discussed in the media (and often in academic presentations) as if they were spread more or less evenly across society

1

In this chapter, we introduce greater discrimination into that description. Unquestionably, the late twentieth century has seen profound changes in the structure of the family. But it is easy to misperceive what is going on. The differences across socioeconomic classes are large, and they reflect important differences by cognitive class as well.

Marriage is a fundamental building block of social life and society itself and thus is a good place to start, because this is one area where much has changed and little has changed, depending on the vantage point one takes.

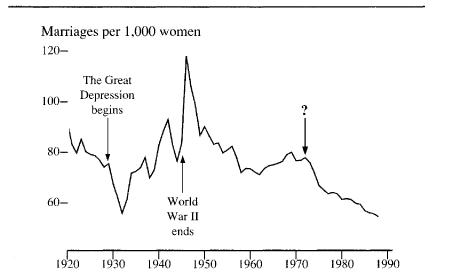

From a demographic perspective, the changes are huge, as shown in the next figure. The marriage rate since the 1920s has been volatile, but the valleys and peaks in the figure have explanations that do not necessarily involve the underlying propensity to marry. The Great Depression probably had a lot to do with the valley in the early 1930s, and World War II not only had a lot to do with the spike in the late 1940s but may well have had reverberations on the marriage rate that lasted into the 1950s. It could even be argued that once these disruptive events are taken into account, the underlying propensity to marry did not change from 1930 to the early 1970s. The one prolonged decline for which there is no obvious explanation

except

a change in the propensity to marry began in 1973, when marriage rates per 1,000 women began dropping and have been dropping ever since, in good years and bad. In 1987, the nation passed a landmark: Marriage rates hit an all-time low, dropping below the previous mark set in the depths of the depression. A new record was promptly set again in 1988.

This change, apparently reflecting some bedrock shifts in attitudes toward marriage in postindustrial societies, may have profound significance.

And yet marriage is still alive and well in the sense that it remains a hugely popular institution. Over 90 percent of Americans of both sexes have married by the time they reach their 40s.

2

In the early 1970s, the marriage rate began a prolonged decline for no immediately apparent reason

Sources:

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1975, Table B214-215;

SAUS,

1992, Table 127, and comparable tables in various editions.

What does cognitive ability have to do with marriage, and is there any reason to think that it could be interacting with society’s declining propensity to marry?

We know from work by Robert Retherford that in premodern societies the wealthy and successful married at younger ages than the poor and underprivileged.

3

Retherford further notes that intelligence and social status are correlated wherever they have been examined; hence, we can assume that intelligence—via social status—facilitated’marriage in premodern societies.

With the advent of modernity, however, this relationship flips over. Throughout the West since the nineteenth century, people in the more

privileged sector of society have married later and at lower rates than the less privileged. We examine the demographic implications of this phenomenon in Chapter 15. For now, the implication is that in late-twentieth-century America, we should expect to find lower marriage rates among the highly intelligent in the NLSY.