Ten Days in a Mad-House and Other Stories (8 page)

Read Ten Days in a Mad-House and Other Stories Online

Authors: Nellie Bly

Tags: #Psychology, #Medical, #General, #Psychiatry, #Mental Illness, #People With Disabilities, #Hospital Administration & Care, #Biography & Autobiography, #Editors; Journalists; Publishers, #Social Science

face.”

This woman was too clever, I concluded, and was glad to answer the

roughly given orders to follow the nurse to see the doctor. This

nurse, Miss Grupe, by the way, had a nice German face, and if I had

not detected certain hard lines about the mouth I might have

expected, as did my companions, to receive but kindness from her.

She left us in a small waiting-room at the end of the hall, and left us

alone while she went into a small office opening into the sitting or

receiving-room.

“I like to go down in the wagon,” she said to the invisible party on

the inside. “It helps to break up the day.” He answered her that the

open air improved her looks, and she again appeared before us all

smiles and simpers.

“Come here, Tillie Mayard,” she said. Miss Mayard obeyed, and,

though I could not see into the office, I could hear her gently but

firmly pleading her case. All her remarks were as rational as any I

ever heard, and I thought no good physician could help but be

impressed with her story. She told of her recent illness, that she was

suffering from nervous debility. She begged that they try all their

tests for insanity, if they had any, and give her justice. Poor girl, how

my heart ached for her! I determined then and there that I would try

by every means to make my mission of benefit to my suffering

Ten Days in a Mad-House

sisters; that I would show how they are committed without ample

trial. Without one word of sympathy or encouragement she was

brought back to where we sat.

Mrs. Louise Schanz was taken into the presence of Dr. Kinier, the

medical man.

“Your name?” he asked, loudly. She answered in German, saying

she did not speak English nor could she understand it. However,

when he said Mrs. Louise Schanz, she said “Yah, yah.” Then he tried

other questions, and when he found she could not understand one

world of English, he said to Miss Grupe:

“You are German; speak to her for me.”

Miss Grupe proved to be one of those people who are ashamed of

their nationality, and she refused, saying she could understand but

few worlds of her mother tongue.

“You know you speak German. Ask this woman what her husband

does,” and they both laughed as if they were enjoying a joke.

“I can’t speak but a few words,” she protested, but at last she

managed to ascertain the occupation of Mr. Schanz.

“Now, what was the use of lying to me?” asked the doctor, with a

laugh which dispelled the rudeness.

“I can’t speak any more,” she said, and she did not.

Thus was Mrs. Louise Schanz consigned to the asylum without a

chance of making herself understood. Can such carelessness be

excused, I wonder, when it is so easy to get an interpreter? If the confinement was but for a few days one might question the

necessity. But here was a woman taken without her own consent

from the free world to an asylum and there given no chance to prove

her sanity. Confined most probably for life behind asylum bars,

without even being told in her language the why and wherefore.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

Compare this with a criminal, who is given every chance to prove his

innocence. Who would not rather be a murderer and take the chance

for life than be declared insane, without hope of escape? Mrs. Schanz

begged in German to know where she was, and pleaded for liberty.

Her voice broken by sobs, she was led unheard out to us.

Mrs. Fox was then put through this weak, trifling examination and

brought from the office, convicted. Miss Annie Neville took her turn,

and I was again left to the last. I had by this time determined to act

as I do when free, except that I would refuse to tell who I was or

where my home was.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

CHAPTER IX.

AN EXPERT(?) AT WORK.

“NELLIE BROWN, the doctor wants you,” said Miss Grupe. I went

in and was told to sit down opposite Dr. Kinier at the desk.

“What is your name?” he asked, without looking up.

“Nellie Brown,” I replied easily.

“Where is your home?” writing what I had said down in a large

book.

“In Cuba.”

“Oh!” he ejaculated, with sudden understanding–then, addressing

the nurse:

“Did you see anything in the papers about her?”

“Yes,” she replied, “I saw a long account of this girl in the

Sun

on

Sunday.” Then the doctor said:

“Keep her here until I go to the office and see the notice again.”

He left us, and I was relieved of my hat and shawl. On his return, he

said he had been unable to find the paper, but he related the story of

my

debut

, as he had read it, to the nurse.

“What’s the color of her eyes?”

Miss Grupe looked, and answered “gray,” although everybody had

always said my eyes were brown or hazel.

“What’s your age?” he asked; and as I answered, “Nineteen last

May,” he turned to the nurse, and said, “When do you get your next

pass?” This I ascertained was a leave of absence, or “a day off.”

Ten Days in a Mad-House

“Next Saturday,” she said, with a laugh.

“You will go to town?” and they both laughed as she answered in

the affirmative, and he said:

“Measure her.” I was stood under a measure, and it was brought

down tightly on my head.

“What is it?” asked the doctor.

“Now you know I can’t tell,” she said.

“Yes, you can; go ahead. What height?”

“I don’t know; there are some figures there, but I can’t tell.”

“Yes, you can. Now look and tell me.”

“I can’t; do it yourself,” and they laughed again as the doctor left his

place at the desk and came forward to see for himself.

“Five feet five inches; don’t you see?” he said, taking her hand and

touching the figures.

By her voice I knew she did not understand yet, but that was no

concern of mine, as the doctor seemed to find a pleasure in aiding

her. Then I was put on the scales, and she worked around until she

got them to balance.

“How much?” asked the doctor, having resumed his position at the

desk.

“I don’t know. You will have to see for yourself,” she replied, calling

him by his Christian name, which I have forgotten. He turned and

also addressing her by her baptismal name, he said:

“You are getting too fresh!” and they both laughed. I then told the

weight–112 pounds–to the nurse, and she in turn told the doctor.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

“What time are you going to supper?” he asked, and she told him.

He gave the nurse more attention than he did me, and asked her six

questions to every one of me. Then he wrote my fate in the book

before him. I said, “I am not sick and I do not want to stay here. No

one has a right to shut me up in this manner.” He took no notice of

my remarks, and having completed his writings, as well as his talk

with the nurse for the moment, he said that would do, and with my

companions, I went back to the sitting-room.

“You play the piano?” they asked.

“Oh, yes; ever since I was a child,” I replied.

Then they insisted that I should play, and they seated me on a

wooden chair before an old-fashioned square. I struck a few notes,

and the untuned response sent a grinding chill through me.

“How horrible,” I exclaimed, turning to a nurse, Miss McCarten,

who stood at my side. “I never touched a piano as much out of

tune.”

“It’s a pity of you,” she said, spitefully; “we’ll have to get one made

to order for you.”

I began to play the variations of “Home Sweet Home.” The talking

ceased and every patient sat silent, while my cold fingers moved

slowly and stiffly over the keyboard. I finished in an aimless fashion

and refused all requests to play more. Not seeing an available place

to sit, I still occupied the chair in the front of the piano while I “sized

up” my surroundings.

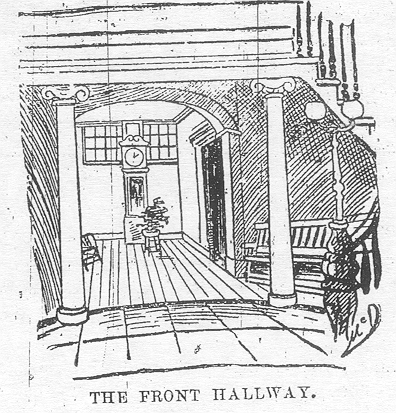

It was a long, bare room, with bare yellow benches encircling it.

These benches, which were perfectly straight, and just as

uncomfortable, would hold five people, although in almost every

instance six were crowded on them. Barred windows, built about

five feet from the floor, faced the two double doors which led into

the hall. The bare white walls were somewhat relieved by three

lithographs, one of Fritz Emmet and the others of negro minstrels. In

Ten Days in a Mad-House

the center of the room was a large table covered with a white bed-

spread, and around it sat the nurses. Everything was spotlessly clean

and I thought what good workers the nurses must be to keep such

order. In a few days after how I laughed at my own stupidity to

think the nurses would work. When they found I would not play

any more, Miss McCarten came up to me saying, roughly:

“Get away from here,” and closed the piano with a bang.

“Brown, come here,” was the next order I got from a rough, red-

faced woman at the table. “What have you on?”

“My clothing,” I replied.

She lifted my dress and skirts and wrote down one pair shoes, one

pair stockings, one cloth dress, one straw sailor hat, and so on.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

CHAPTER X.

MY FIRST SUPPER.

THIS examination over, we heard some one yell, “Go out into the

hall.” One of the patients kindly explained that this was an invitation

to supper. We late comers tried to keep together, so we entered the

hall and stood at the door where all the women had crowded. How

we shivered as we stood there! The windows were open and the

draught went whizzing through the hall. The patients looked blue

with cold, and the minutes stretched into a quarter of an hour. At

last one of the nurses went forward and unlocked a door, through

which we all crowded to a landing of the stairway. Here again came

a long halt directly before an open window.

“How very imprudent for the attendants to keep these thinly clad

women standing here in the cold,” said Miss Neville.

I looked at the poor crazy captives shivering, and added,

emphatically, “It’s horribly brutal.” While they stood there I thought

I would not relish supper that night. They looked so lost and

hopeless. Some were chattering nonsense to invisible persons, others

were laughing or crying aimlessly, and one old, gray-haired woman

was nudging me, and, with winks and sage noddings of the head

and pitiful uplifting of the eyes and hands, was assuring me that I

must not mind the poor creatures, as they were all mad. “Stop at the

heater,” was then ordered, “and get in line, two by two.” “Mary, get

a companion.” “How many times must I tell you to keep in line?”

“Stand still,” and, as the orders were issued, a shove and a push

were administered, and often a slap on the ears. After this third and

final halt, we were marched into a long, narrow dining-room, where

a rush was made for the table.

The table reached the length of the room and was uncovered and

uninviting. Long benches without backs were put for the patients to

sit on, and over these they had to crawl in order to face the table.

Placed closed together all along the table were large dressing-bowls

filled with a pinkish-looking stuff which the patients called tea. By

Ten Days in a Mad-House

each bowl was laid a piece of bread, cut thick and buttered. A small

saucer containing five prunes accompanied the bread. One fat

woman made a rush, and jerking up several saucers from those

around her emptied their contents into her own saucer. Then while

holding to her own bowl she lifted up another and drained its

contents at one gulp. This she did to a second bowl in shorter time

than it takes to tell it. Indeed, I was so amused at her successful

grabbings that when I looked at my own share the woman opposite,

without so much as by your leave, grabbed my bread and left me

without any.

Another patient, seeing this, kindly offered me hers, but I declined

with thanks and turned to the nurse and asked for more. As she

flung a thick piece down on the table she made some remark about