Ten Days in a Mad-House and Other Stories (6 page)

Read Ten Days in a Mad-House and Other Stories Online

Authors: Nellie Bly

Tags: #Psychology, #Medical, #General, #Psychiatry, #Mental Illness, #People With Disabilities, #Hospital Administration & Care, #Biography & Autobiography, #Editors; Journalists; Publishers, #Social Science

the patients to gather ‘round the feast; then she brought out a small

tin plate on which was a piece of boiled meat and a potato. It could

not have been colder had it been cooked the week before, and it had

no chance to make acquaintance with salt or pepper. I would not go

Ten Days in a Mad-House

up to the table, so Mary came to where I sat in a corner, and while

handing out the tin plate, asked:

“Have ye any pennies about ye, dearie?”

“What?” I said, in my surprise.

“Have ye any pennies, dearie, that ye could give me. They’ll take

them all from ye any way, dearie, so I might as well have them.”

I understood it fully now, but I had no intention of feeing Mary so

early in the game, fearing it would have an influence on her

treatment of me, so I said I had lost my purse, which was quite true.

But though I did not give Mary any money, she was none the less

kind to me. When I objected to the tin plate in which she had

brought my food she fetched a china one for me, and when I found it

impossible to eat the food she presented she gave me a glass of milk

and a soda cracker.

All the windows in the hall were open and the cold air began to tell

on my Southern blood. It grew so cold indeed as to be almost

unbearable, and I complained of it to Miss Scott and Miss Ball. But

they answered curtly that as I was in a charity place I could not

expect much else. All the other women were suffering from the cold,

and the nurses themselves had to wear heavy garments to keep

themselves warm. I asked if I could go to bed. They said “No!” At

last Miss Scott got an old gray shawl, and shaking some of the moths

out of it, told me to put it on.

“It’s rather a bad-looking shawl,” I said.

“Well, some people would get along better if they were not so

proud,” said Miss Scott. “People on charity should not expect

anything and should not complain.”

So I put the moth-eaten shawl, with all its musty smell, around me,

and sat down on a wicker chair, wondering what would come next,

whether I should freeze to death or survive. My nose was very cold,

Ten Days in a Mad-House

so I covered up my head and was in a half doze, when the shawl was

suddenly jerked from my face and a strange man and Miss Scott

stood before me. The man proved to be a doctor, and his first

greetings were:

“I’ve seen that face before.”

“Then you know me?” I asked, with a great show of eagerness that I

did not feel.

“I think I do. Where did you come from?”

“From home.”

“Where is home?”

“Don’t you know? Cuba.”

He then sat down beside me, felt my pulse, and examined my

tongue, and at last said:

Ten Days in a Mad-House

“Tell Miss Scott all about yourself.”

“No, I will not. I will not talk with women.”

“What do you do in New York?”

“Nothing.”

“Can you work?”

“No, senor.”

“Tell me, are you a woman of the town?”

“I do not understand you,” I replied, heartily disgusted with him.

“I mean have you allowed the men to provide for you and keep

you?”

I felt like slapping him in the face, but I had to maintain my

composure, so I simply said:

“I do not know what you are talking about. I always lived at home.”

After many more questions, fully as useless and senseless, he left me

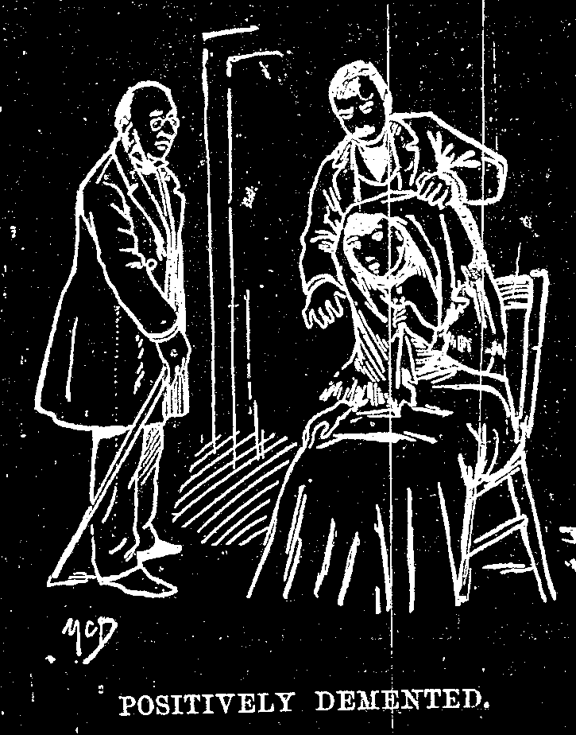

and began to talk with the nurse. “Positively demented,” he said. “I

consider it a hopeless case. She needs to be put where some one will

take care of her.”

And so I passed my second medical expert.

After this, I began to have a smaller regard for the ability of doctors

than I ever had before, and a greater one for myself. I felt sure now

that no doctor could tell whether people were insane or not, so long

as the case was not violent.

Later in the afternoon a boy and a woman came. The woman sat

down on a bench, while the boy went in and talked with Miss Scott.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

In a short time he came out, and, just nodding good-bye to the

woman, who was his mother, went away. She did not look insane,

but as she was German I could not learn her story. Her name,

however, was Mrs. Louise Schanz. She seemed quite lost, but when

the nurses put her at some sewing she did her work well and

quickly. At three in the afternoon all the patients were given a gruel

broth, and at five a cup of tea and a piece of bread. I was favored; for

when they saw that it was impossible for me to eat the bread or

drink the stuff honored by the name of tea, they gave me a cup of

milk and a cracker, the same as I had had at noon.

Just as the gas was being lighted another patient was added. She was

a young girl, twenty-five years old. She told me that she had just

gotten up from a sick bed. Her appearance confirmed her story. She

looked like one who had had a severe attack of fever. “I am now

suffering from nervous debility,” she said, “and my friends have

sent me here to be treated for it.” I did not tell her where she was,

and she seemed quite satisfied. At 6.15 Miss Ball said that she

wanted to go away, and so we would all have to go to bed. Then

each of us–we now numbered six–were assigned a room and told to

undress. I did so, and was given a short, cotton-flannel gown to wear

during the night. Then she took every particle of the clothing I had

worn during the day, and, making it up in a bundle, labeled it

“Brown,” and took it away. The iron-barred window was locked,

and Miss Ball, after giving me an extra blanket, which, she said, was

a favor rarely granted, went out and left me alone. The bed was not a

comfortable one. It was so hard, indeed, that I could not make a dent

in it; and the pillow was stuffed with straw. Under the sheet was an

oilcloth spread. As the night grew colder I tried to warm that

oilcloth. I kept on trying, but when morning dawned and it was still

as cold as when I went to bed, and had reduced me too, to the

temperature of an iceberg, I gave it up as an impossible task.

I had hoped to get some rest on this my first night in an insane

asylum. But I was doomed to disappointment. When the night

nurses came in they were curious to see me and to find out what I

was like. No sooner had they left than I heard some one at my door

inquiring for Nellie Brown, and I began to tremble, fearing always

Ten Days in a Mad-House

that my sanity would be discovered. By listening to the conversation

I found it was a reporter in search of me, and I heard him ask for my

clothing so that he might examine it. I listened quite anxiously to the

talk about me, and was relieved to learn that I was considered

hopelessly insane. That was encouraging. After the reporter left I

heard new arrivals, and I learned that a doctor was there and

intended to see me. For what purpose I knew not, and I imagined all

sorts of horrible things, such as examinations and the rest of it, and

when they got to my room I was shaking with more than fear.

“Nellie Brown, here is the doctor; he wishes to speak with you,” said

the nurse. If that’s all he wanted I thought I could endure it. I

removed the blanket which I had put over my head in my sudden

fright and looked up. The sight was reassuring.

He was a handsome young man. He had the air and address of a

gentleman. Some people have since censured this action; but I feel

sure, even if it was a little indiscreet, that they young doctor only

meant kindness to me. He came forward, seated himself on the side

of my bed, and put his arm soothingly around my shoulders. It was

a terrible task to play insane before this young man, and only a girl

can sympathize with me in my position.

“How do you feel to-night, Nellie?” he asked, easily.

“Oh, I feel all right.”

“But you are sick, you know,” he said.

“Oh, am I?” I replied, and I turned by head on the pillow and smiled.

“When did you leave Cuba, Nellie?”

“Oh, you know my home?” I asked.

“Yes, very well. Don’t you remember me? I remember you.”

Ten Days in a Mad-House

“Do you?” and I mentally said I should not forget him. He was

accompanied by a friend who never ventured a remark, but stood

staring at me as I lay in bed. After a great many questions, to which I

answered truthfully, he left me. Then came other troubles. All night

long the nurses read one to the other aloud, and I know that the

other patients, as well as myself, were unable to sleep. Every half-

hour or hour they would walk heavily down the halls, their boot-

heels resounding like the march of a private of dragoons, and take a

look at every patient. Of course this helped to keep us awake. Then

as it came toward morning, they began to beat eggs for breakfast,

and the sound made me realize how horribly hungry I was.

Occasional yells and cries came from the male department, and that

did not aid in making the night pass more cheerfully. Then the

ambulance-gong, as it brought in more unfortunates, sounded as a

knell to life and liberty. Thus I passed my first night as an insane girl

at Bellevue.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

CHAPTER VII.

THE GOAL IN SIGHT.

AT 6 o’clock on Sunday morning, Sept. 25, the nurses pulled the

covering from my bed. “Come, it’s time for you to get out of bed,”

they said, and opened the window and let in the cold breeze. My

clothing was then returned to me. After dressing I was shown to a

washstand, where all the other patients were trying to rid their faces

of all traces of sleep. At 7 o’clock we were given some horrible mess,

which Mary told us was chicken broth. The cold, from which we had

suffered enough the day previous, was bitter, and when I

complained to the nurse she said it was one of the rules of the

institution not to turn the heat on until October, and so we would

have to endure it, as the steam-pipes had not even been put in order.

The night nurses then, arming themselves with scissors, began to

play manicure on the patients. They cut my nails to the quick, as

they did those of several of the other patients. Shortly after this a

handsome young doctor made his appearance and I was conducted

into the sitting-room.

“Who are you?” he asked.

“Nellie Moreno,” I replied.

“Then why did you give the name of Brown?” he asked. “What is

wrong with you?”

“Nothing. I did not want to come here, but they brought me. I want

to go away. Won’t you let me out?”

“If I take you out will you stay with me? Won’t you run away from

me when you get on the street?”

“I can’t promise that I will not,” I answered, with a smile and a sigh,

for he was handsome.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

He asked me many other questions. Did I ever see faces on the wall?

Did I ever hear voices around? I answered him to the best of my

ability.

“Do you ever hear voices at night?” he asked.

“Yes, there is so much talking I cannot sleep.”

“I thought so,” he said to himself. Then turning to me, he asked:

“What do these voices say?”

“Well, I do not listen to them always. But sometimes, very often,

they talk about Nellie Brown, and then on other subjects that do not

interest me half so much,” I answered, truthfully.

“That will do,” he said to Miss Scott, who was just on the outside.

“Can I go away?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said, with a satisfied laugh, “we’ll soon send you away.”

“It is so very cold here, I want to go out,” I said.

“That’s true,” he said to Miss Scott. “The cold is almost unbearable in

here, and you will have some cases of pneumonia if you are not

careful.”

With this I was led away and another patient was taken in. I sat right

outside the door and waited to hear how he would test the sanity of

the other patients. With little variation the examination was exactly

the same as mine. All the patients were asked if they saw faces on

the wall, heard voices, and what they said. I might also add each