Ten Days in a Mad-House and Other Stories (10 page)

Read Ten Days in a Mad-House and Other Stories Online

Authors: Nellie Bly

Tags: #Psychology, #Medical, #General, #Psychiatry, #Mental Illness, #People With Disabilities, #Hospital Administration & Care, #Biography & Autobiography, #Editors; Journalists; Publishers, #Social Science

patients, into a straight tight waist sewed on to a straight skirt. As I

buttoned the waist I noticed the underskirt was about six inches

longer than the upper, and for a moment I sat down on the bed and

laughed at my own appearance. No woman ever longed for a mirror

more than I did at that moment.

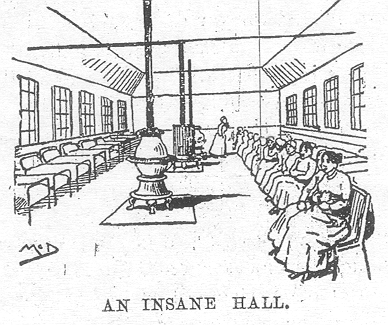

I saw the other patients hurrying past in the hall, so I decided not to

lose anything that might be going on. We numbered forty-five

Ten Days in a Mad-House

patients in Hall 6, and were sent to the bathroom, where there were

two coarse towels. I watched crazy patients who had the most

dangerous eruptions all over their faces dry on the towels and then

saw women with clean skins turn to use them. I went to the bathtub

and washed my face at the running faucet and my underskirt did

duty for a towel.

Before I had completed my ablutions a bench was brought into the

bathroom. Miss Grupe and Miss McCarten came in with combs in

their hands. We were told so sit down on the bench, and the hair of

forty-five women was combed with one patient, two nurses, and six

combs. As I saw some of the sore heads combed I thought this was

another dose I had not bargained for. Miss Tillie Mayard had her

own comb, but it was taken from her by Miss Grady. Oh, that

combing! I never realized before what the expression “I’ll give you a

combing” meant, but I knew then. My hair, all matted and wet from

the night previous, was pulled and jerked, and, after expostulating to

no avail, I set my teeth and endured the pain. They refused to give

me my hairpins, and my hair was arranged in one plait and tied with

a red cotton rag. My curly bangs refused to stay back, so that at least

was left of my former glory.

After this we went to the sitting-room and I looked for my

companions. At first I looked vainly, unable to distinguish them

from the other patients, but after awhile I recognized Miss Mayard

by her short hair.

“How did you sleep after your cold bath?”

“I almost froze, and then the noise kept me awake. It’s dreadful! My

nerves were so unstrung before I came here, and I fear I shall not be

able to stand the strain.”

I did the best I could to cheer her. I asked that we be given additional

clothing, at least as much as custom says women shall wear, but they

told me to shut up; that we had as much as they intended to give us.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

We were compelled to get up at 5.30 o’clock, and at 7.15 we were

told to collect in the hall, where the experience of waiting, as on the

evening previous, was repeated. When we got into the dining-room

at last we found a bowl of cold tea, a slice of buttered bread and a

saucer of oatmeal, with molasses on it, for each patient. I was

hungry, but the food would not down. I asked for unbuttered bread

and was given it. I cannot tell you of anything which is the same

dirty, black color. It was hard, and in places nothing more than dried

dough. I found a spider in my slice, so I did not eat it. I tried the

oatmeal and molasses, but it was wretched, and so I endeavored, but

without much show of success, to choke down the tea.

After we were back to the sitting-room a number of women were

ordered to make the beds, and some of the patients were put to

scrubbing and others given different duties which covered all the

work in the hall. It is not the attendants who keep the institution so

nice for the poor patients, as I had always thought, but the patients,

who do it all themselves–even to cleaning the nurses’ bedrooms and

caring for their clothing.

About 9.30 the new patients, of which I was one, were told to go out

to see the doctor. I was taken in and my lungs and my heart were

examined by the flirty young doctor who was the first to see us the

day we entered. The one who made out the report, if I mistake not,

was the assistant superintendent, Ingram. A few questions and I was

allowed to return to the sitting-room.

I came in and saw Miss Grady with my note-book and long lead

pencil, bought just for the occasion.

“I want my book and pencil,” I said, quite truthfully. “It helps me

remember things.”

I was very anxious to get it to make notes in and was disappointed

when she said:

“You can’t have it, so shut up.”

Ten Days in a Mad-House

Some days after I asked Dr. Ingram if I could have it, and he

promised to consider the matter. When I again referred to it, he said

that Miss Grady said I only brought a book there; and that I had no

pencil. I was provoked, and insisted that I had, whereupon I was

advised to fight against the imaginations of my brain.

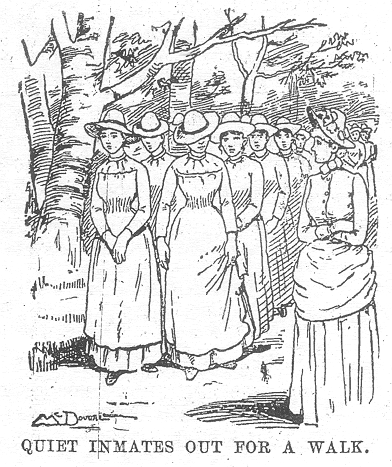

After the housework was completed by the patients, and as day was

fine, but cold, we were told to go out in the hall and get on shawls

and hats for a walk. Poor patients! How eager they were for a breath

of air; how eager for a slight release from their prison. They went

swiftly into the hall and there was a skirmish for hats. Such hats!

Ten Days in a Mad-House

CHAPTER XII.

PROMENADING WITH LUNATICS.

I SHALL never forget my first walk. When all the patients had

donned the white straw hats, such as bathers wear at Coney Island, I

could not but laugh at their comical appearances. I could not

distinguish one woman from another. I lost Miss Neville, and had to

take my hat off and search for her. When we met we put our hats on

and laughed at one another. Two by two we formed in line, and

guarded by the attendants we went out a back way on to the walks.

We had not gone many paces when I saw, proceeding from every

walk, long lines of women guarded by nurses. How many there

were! Every way I looked I could see them in the queer dresses,

comical straw hats and shawls, marching slowly around. I eagerly

watched the passing lines and a thrill of horror crept over me at the

sight. Vacant eyes and meaningless faces, and their tongues uttered

meaningless nonsense. One crowd passed and I noted by nose as

well as eyes, that they were fearfully dirty.

“Who are they?” I asked of a patient near me.

“They are considered the most violent on the island,” she replied.

“They are from the Lodge, the first building with the high steps.”

Some were yelling, some were cursing, others were singing or

praying or preaching, as the fancy struck them, and they made up

the most miserable collection of humanity I had ever seen. As the din

of their passing faded in the distance there came another sight I can

never forget:

A long cable rope fastened to wide leather belts, and these belts

locked around the waists of fifty-two women. At the end of the rope

was a heavy iron cart, and in it two women–one nursing a sore foot,

another screaming at some nurse, saying: “You beat me and I shall

not forget it. You want to kill me,” and then she would sob and cry.

The women “on the rope,” as the patients call it, were each busy on

their individual freaks. Some were yelling all the while. One who

Ten Days in a Mad-House

had blue eyes saw me look at her, and she turned as far as she could,

talking and smiling, with that terrible, horrifying look of absolute

insanity stamped on her. The doctors might safely judge on her case.

The horror of that sight to one who had never been near an insane

person before, was something unspeakable.

“God help them!” breathed Miss Neville. “It is so dreadful I cannot

look.”

On they passed, but for their places to be filled by more. Can you

imagine the sight? According to one of the physicians there are 1600

insane women on Blackwell’s Island.

Mad! what can be half so horrible? My heart thrilled with pity when

I looked on old, gray-haired women talking aimlessly to space. One

woman had on a straightjacket, and two women had to drag her

along. Crippled, blind, old, young, homely, and pretty; one senseless

mass of humanity. No fate could be worse.

I looked at the pretty lawns, which I had once thought was such a

comfort to the poor creatures confined on the Island, and laughed at

my own notions. What enjoyment is it to them? They are not allowed

on the grass–it is only to look at. I saw some patients eagerly and

caressingly lift a nut or a colored leaf that had fallen on the path. But

they were not permitted to keep them. The nurses would always

compel them to throw their little bit of God’s comfort away.

As I passed a low pavilion, where a crowd of helpless lunatics were

confined, I read a motto on the wall, “While I live I hope.” The

absurdity of it struck me forcibly. I would have liked to put above

the gates that open to the asylum, “He who enters here leaveth hope

behind.”

During the walk I was annoyed a great deal by nurses who had

heard my romantic story calling to those in charge of us to ask which

one I was. I was pointed out repeatedly.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

It was not long until the dinner hour arrived and I was so hungry

that I felt I could eat anything. The same old story of standing for a

half and three-quarters of an hour in the hall was repeated before we

got down to our dinners. The bowls in which we had had our tea

were now filled with soup, and on a plate was one cold boiled potato

and a chunk of beef, which on investigation, proved to be slightly

spoiled. There were no knives or forks, and the patients looked fairly

savage as they took the tough beef in their fingers and pulled in

opposition to their teeth. Those toothless or with poor teeth could

not eat it. One tablespoon was given for the soup, and a piece of

bread was the final entree. Butter is never allowed at dinner nor

coffee or tea. Miss Mayard could not eat, and I saw many of the sick

ones turn away in disgust. I was getting very weak from the want of

food and tried to eat a slice of bread. After the first few bites hunger

asserted itself, and I was able to eat all but the crusts of the one slice.

Superintendent Dent went through the sitting-room, giving an

occasional “How do you do?” “How are you to-day?” here and there

among the patients. His voice was as cold as the hall, and the

patients made no movement to tell him of their sufferings. I asked

Ten Days in a Mad-House

some of them to tell how they were suffering from the cold and

insufficiency of clothing, but they replied that the nurse would beat

them if they told.

I was never so tired as I grew sitting on those benches. Several of the

patients would sit on one foot or sideways to make a change, but

they were always reproved and told to sit up straight. If they talked

they were scolded and told to shut up; if they wanted to walk

around in order to take the stiffness out of them, they were told to sit

down and be still. What, excepting torture, would produce insanity

quicker than this treatment? Here is a class of women sent to be

cured. I would like the expert physicians who are condemning me

for my action, which has proven their ability, to take a perfectly sane

and healthy woman, shut her up and make her sit from 6 A. M. until

8 P. M. on straight-back benches, do not allow her to talk or move