Ten Days in a Mad-House and Other Stories (13 page)

Read Ten Days in a Mad-House and Other Stories Online

Authors: Nellie Bly

Tags: #Psychology, #Medical, #General, #Psychiatry, #Mental Illness, #People With Disabilities, #Hospital Administration & Care, #Biography & Autobiography, #Editors; Journalists; Publishers, #Social Science

“The remembrance of that is enough to make me mad. For crying the

nurses beat me with a broom-handle and jumped on me, injuring me

internally, so that I shall never get over it. Then they tied my hands

and feet, and, throwing a sheet over my head, twisted it tightly

around my throat, so I could not scream, and thus put me in a

bathtub filled with cold water. They held me under until I gave up

Ten Days in a Mad-House

every hope and became senseless. At other times they took hold of

my ears and beat my head on the floor and against the wall. Then

they pulled out my hair by the roots, so that it will never grow in

again.”

Mrs. Cotter here showed me proofs of her story, the dent in the back

of her head and the bare spots where the hair had been taken out by

the handful. I give her story as plainly as possible: “My treatment

was not as bad as I have seen others get in there, but it has ruined

my health, and even if I do get out of here I will be a wreck. When

my husband heard of the treatment given me he threatened to

expose the place if I was not removed, so I was brought here. I am

well mentally now. All that old fear has left me, and the doctor has

promised to allow my husband to take me home.”

I made the acquaintance of Bridget McGuinness, who seems to be

sane at the present time. She said she was sent to Retreat 4, and put

on the “rope gang.” “The beating I got there were something

dreadful. I was pulled around by the hair, held under the water until

I strangled, and I was choked and kicked. The nurses would always

keep a quiet patient stationed at the window to tell them when any

of the doctors were approaching. It was hopeless to complain to the

doctors, for they always said it was the imagination of our diseased

brains, and besides we would get another beating for telling. They

would hold patients under the water and threaten to leave them to

die there if they did not promise not to tell the doctors. We would all

promise, because we knew the doctors would not help us, and we

would do anything to escape the punishment. After breaking a

window I was transferred to the Lodge, the worst place on the

island. It is dreadfully dirty in there, and the stench is awful. In the

summer the flies swarm the place. The food is worse than we get in

other wards and we are given only tin plates. Instead of the bars

being on the outside, as in this ward, they are on the inside. There

are many quiet patients there who have been there for years, but the

nurses keep them to do the work. Among other beating I got there,

the nurses jumped on me once and broke two of my ribs.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

“While I was there a pretty young girl was brought in. She had been

sick, and she fought against being put in that dirty place. One night

the nurses took her and, after beating her, they held her naked in a

cold bath, then they threw her on her bed. When morning came the

girl was dead. The doctors said she died of convulsions, and that

was all that was done about it.

“They inject so much morphine and chloral that the patients are

made crazy. I have seen the patients wild for water from the effect of

the drugs, and the nurses would refuse it to them. I have heard

women beg for a whole night for one drop and it was not given

them. I myself cried for water until my mouth was so parched and

dry that I could not speak.”

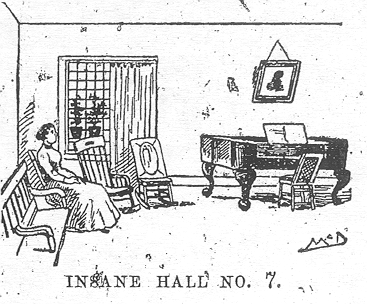

I saw the same thing myself in hall 7. The patients would beg for a

drink before retiring, but the nurses–Miss Hart and the others–

refused to unlock the bathroom that they might quench their thirst.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

CHAPTER XV.

INCIDENTS OF ASYLUM LIFE.

THERE is little in the wards to help one pass the time. All the asylum

clothing is made by the patients, but sewing does not employ one’s

mind. After several months’ confinement the thoughts of the busy

world grow faint, and all the poor prisoners can do is to sit and

ponder over their hopeless fate. In the upper halls a good view is

obtained of the passing boats and New York. Often I tried to picture

to myself as I looked out between the bars to the lights faintly

glimmering in the city, what my feelings would be if I had no one to

obtain my release.

I have watched patients stand and gaze longingly toward the city

they in all likelihood will never enter again. It means liberty and life;

it seems so near, and yet heaven is not further from hell.

Do the women pine for home? Excepting the most violent cases, they

are conscious that they are confined in an asylum. An only desire

that never dies is the one for release, for home.

One poor girl used to tell me every morning, “I dreamed of my

mother last night. I think she may come to-day and take me home.”

That one thought, that longing, is always present, yet she has been

confined some four years.

What a mysterious thing madness is. I have watched patients whose

lips are forever sealed in a perpetual silence. They live, breathe, eat;

the human form is there, but that something, which the body can live

without, but which cannot exist without the body, was missing. I

have wondered if behind those sealed lips there were dreams we ken

not of, or if all was blank?

Still, as sad are those cases when the patients are always conversing

with invisible parties. I have seen them wholly unconscious of their

surroundings and engrossed with an invisible being. Yet, strange to

say, that any command issued to them is always obeyed, in about the

Ten Days in a Mad-House

same manner as a dog obeys his master. One of the most pitiful

delusions of any of the patients was that of a blue-eyed Irish girl,

who believed she was forever damned because of one act in her life.

Her horrible cry, morning and night, “I am damned for all eternity!”

would strike horror to my soul. Her agony seemed like a glimpse of

the inferno.

After being transferred to hall 7 I was locked in a room every night

with six crazy women. Two of them seemed never to sleep, but spent

the night in raving. One would get out of her bed and creep around

the room searching for some one she wanted to kill. I could not help

but think how easy it would be for her to attack any of the other

patients confined with her. It did not make the night more

comfortable.

One middle-aged woman, who used to sit always in the corner of the

room, was very strangely affected. She had a piece of newspaper,

and from it she continually read the most wonderful things I ever

heard. I often sat close by her and listened. History and romance fell

equally well from her lips.

I saw but one letter given a patient while I was there. It awakened a

big interest. Every patient seemed thirsty for a word from the world,

and they crowded around the one who had been so fortunate and

asked hundreds of questions.

Visitors make but little interest and a great deal of mirth. Miss Mattie

Morgan, in hall 7, played for the entertainment of some visitors one

day. They were close about her until one whispered that she was a

patient. “Crazy!” they whispered, audibly, as they fell back and left

her alone. She was amused as well as indignant over the episode.

Miss Mattie, assisted by several girls she has trained, makes the

evenings pass very pleasantly in hall 7. They sing and dance. Often

the doctors come up and dance with the patients.

One day when we went down to dinner we heard a weak little cry in

the basement. Every one seemed to notice it, and it was not long

until we knew there was a baby down there. Yes, a baby. Think of it–

Ten Days in a Mad-House

a little, innocent babe born in such a chamber of horrors! I can

imagine nothing more terrible.

A visitor who came one day brought in her arms her babe. A mother

who had been separated from her five little children asked

permission to hold it. When the visitor wanted to leave, the woman’s

grief was uncontrollable, as she begged to keep the babe which she

imagined was her own. It excited more patients than I had ever seen

excited before at one time.

The only amusement, if so it may be called, given the patients

outside, is a ride once a week, if the weather permits, on the “merry-

go-round.” It is a change, and so they accept it with some show of pleasure.

A scrub-brush factory, a mat factory, and the laundry, are where the

mild patients work. They get no recompense for it, but they get

hungry over it.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

CHAPTER XVI.

THE LAST GOOD-BYE.

THE day Pauline Moser was brought to the asylum we heard the

most horrible screams, and an Irish girl, only partly dressed, came

staggering like a drunken person up the hall, yelling, “Hurrah! Three

cheers! I have killed the divil! Lucifer, Lucifer, Lucifer,” and so on,

over and over again. Then she would pull a handful of hair out,

while she exultingly cried, “How I deceived the divils. They always

said God made hell, but he didn’t.” Pauline helped the girl to make

the place hideous by singing the most horrible songs. After the Irish

girl had been there an hour or so, Dr. Dent came in, and as he

walked down the hall, Miss Grupe whispered to the demented girl,

“Here is the devil coming, go for him.” Surprised that she would

give a mad woman such instructions, I fully expected to see the

frenzied creature rush at the doctor. Luckily she did not, but

commenced to repeat her refrain of “Oh, Lucifer.” After the doctor

left, Miss Grupe again tried to excite the woman by saying the

pictured minstrel on the wall was the devil, and the poor creature

began to scream, “You divil, I’ll give it to you,” so that two nurses

had to sit on her to keep her down. The attendants seemed to find

amusement and pleasure in exciting the violent patients to do their

worst.

I always made a point of telling the doctors I was sane and asking to

be released, but the more I endeavored to assure them of my sanity

the more they doubted it.

“What are you doctors here for?” I asked one, whose name I cannot

recall.

“To take care of the patients and test their sanity,” he replied.

“Very well,” I said. “There are sixteen doctors on this island, and

excepting two, I have never seen them pay any attention to the

patients. How can a doctor judge a woman’s sanity by merely

bidding her good morning and refusing to hear her pleas for release?

Ten Days in a Mad-House

Even the sick ones know it is useless to say anything, for the answer

will be that it is their imagination.” “Try every test on me,” I have

urged others, “and tell me am I sane or insane? Try my pulse, my

heart, my eyes; ask me to stretch out my arm, to work my fingers, as

Dr. Field did at Bellevue, and then tell me if I am sane.” They would

not heed me, for they thought I raved.

Again I said to one, “You have no right to keep sane people here. I

am sane, have always been so and I must insist on a thorough

examination or be released. Several of the women here are also sane.

Why can’t they be free?”

“They are insane,” was the reply, “and suffering from delusions.”

After a long talk with Dr. Ingram, he said, “I will transfer you to a

quieter ward.” An hour later Miss Grady called me into the hall, and,

after calling me all the vile and profane names a woman could ever

remember, she told me that it was a lucky thing for my “hide” that I

was transferred, or else she would pay me for remembering so well

to tell Dr. Ingram everything. “You d—n hussy, you forget all about

yourself, but you never forget anything to tell the doctor.” After

calling Miss Neville, whom Dr. Ingram also kindly transferred, Miss

Grady took us to the hall above, No. 7.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

In hall 7 there are Mrs. Kroener, Miss Fitzpatrick, Miss Finney, and

Miss Hart. I did not see as cruel treatment as down-stairs, but I heard

them make ugly remarks and threats, twist the fingers and slap the