Ten Days in a Mad-House and Other Stories (4 page)

Read Ten Days in a Mad-House and Other Stories Online

Authors: Nellie Bly

Tags: #Psychology, #Medical, #General, #Psychiatry, #Mental Illness, #People With Disabilities, #Hospital Administration & Care, #Biography & Autobiography, #Editors; Journalists; Publishers, #Social Science

and then Mrs. Stanard gave him a lot of information about me–told

him how strangely I had acted at her home; how I had not slept a

wink all night, and that in her opinion I was a poor unfortunate who

had been driven crazy by inhuman treatment. There was some

discussion between Mrs. Standard and the two officers, and Tom

Bockert was told to take us down to the court in a car.

“Come along,” Bockert said, “I will find your trunk for you.” We all

went together, Mrs. Stanard, Tom Bockert, and myself. I said it was

very kind of them to go with me, and I should not soon forget them.

As we walked along I kept up my refrain about my trucks, injecting

occasionally some remark about the dirty condition of the streets and

Ten Days in a Mad-House

the curious character of the people we met on the way. “I don’t think

I have ever seen such people before,” I said. “Who are they?” I

asked, and my companions looked upon me with expressions of

pity, evidently believing I was a foreigner, an emigrant or something

of the sort. They told me that the people around me were working

people. I remarked once more that I thought there were too many

working people in the world for the amount of work to be done, at

which remark Policeman P. T. Bockert eyed me closely, evidently

thinking that my mind was gone for good. We passed several other

policemen, who generally asked my sturdy guardians what was the

matter with me. By this time quite a number of ragged children were

following us too, and they passed remarks about me that were to me

original as well as amusing.

“What’s she up for?” “Say, kop, where did ye get her?” “Where did

yer pull ‘er?” “She’s a daisy!”

Poor Mrs. Stanard was more frightened than I was. The whole

situation grew interesting, but I still had fears for my fate before the

judge.

At last we came to a low building, and Tom Bockert kindly

volunteered the information: “Here’s the express office. We shall

soon find those trunks of yours.”

The entrance to the building was surrounded by a curious crowd

and I did not think my case was bad enough to permit me passing

them without some remark, so I asked if all those people had lost

their trunks.

“Yes,” he said, “nearly all these people are looking for trunks.”

I said, “They all seem to be foreigners, too.” “Yes,” said Tom, “they

are all foreigners just landed. They have all lost their trunks, and it

takes most of our time to help find them for them.”

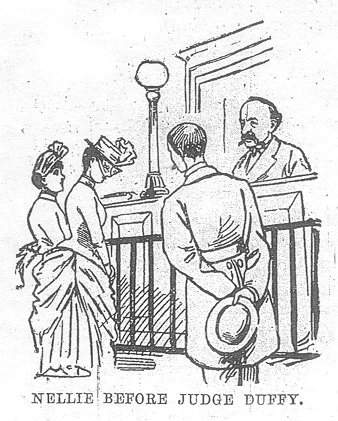

We entered the courtroom. It was the Essex Market Police

Courtroom. At last the question of my sanity or insanity was to be

Ten Days in a Mad-House

decided. Judge Duffy sat behind the high desk, wearing a look which

seemed to indicate that he was dealing out the milk of human

kindness by wholesale. I rather feared I would not get the fate I

sought, because of the kindness I saw on every line of his face, and it

was with rather a sinking heart that I followed Mrs. Stanard as she

answered the summons to go up to the desk, where Tom Bockert

had just given an account of the affair.

“Come here,” said an officer. “What is your name?”

“Nellie Brown,” I replied, with a little accent. “I have lost my trunks,

and would like if you could find them.”

“When did you come to New York?” he asked.

“I did not come to New York,” I replied (while I added, mentally,

“because I have been here for some time.”)

“But you are in New York now,” said the man.

“No,” I said, looking as incredulous as I thought a crazy person

could, “I did not come to New York.”

“That girl is from the west,” he said, in a tone that made me tremble.

“She has a western accent.”

Some one else who had been listening to the brief dialogue here

asserted that he had lived south and that my accent was southern,

while another officer was positive it was eastern. I felt much relieved

when the first spokesman turned to the judge and said:

“Judge, here is a peculiar case of a young woman who doesn’t know

who she is or where she came from. You had better attend to it at

once.”

I commenced to shake with more than the cold, and I looked around

at the strange crowd about me, composed of poorly dressed men and

women with stories printed on their faces of hard lives, abuse and

Ten Days in a Mad-House

poverty. Some were consulting eagerly with friends, while others sat

still with a look of utter hopelessness. Everywhere was a sprinkling

of well-dressed, well-fed officers watching the scene passively and

almost indifferently. It was only an old story with them. One more

unfortunate added to a long list which had long since ceased to be of

any interest or concern to them.

“Come here, girl, and lift your veil,” called out Judge Duffy, in tones

which surprised me by a harshness which I did not think from the

kindly face he possessed.

“Who are you speaking to?” I inquired, in my stateliest manner.

“Come here, my dear, and lift your veil. You know the Queen of

England, if she were here, would have to lift her veil,” he said, very

kindly.

“That is much better,” I replied. “I am not the Queen of England, but

I’ll lift my veil.”

Ten Days in a Mad-House

As I did so the little judge looked at me, and then, in a very kind and

gentle tone, he said:

“My dear child, what is wrong?”

“Nothing is wrong except that I have lost my trunks, and this man,”

indicating Policeman Bockert, “promised to bring me where they

could be found.”

“What do you know about this child?” asked the judge, sternly, of

Mrs. Stanard, who stood, pale and trembling, by my side.

“I know nothing of her except that she came to the home yesterday

and asked to remain overnight.”

“The home! What do you mean by the home?” asked Judge Duffy,

quickly.

“It is a temporary home kept for working women at No. 84 Second

Avenue.”

“What is your position there?”

“I am assistant matron.”

“Well, tell us all you know of the case.”

“When I was going into the home yesterday I noticed her coming

down the avenue. She was all alone. I had just got into the house

when the bell rang and she came in. When I talked with her she

wanted to know if she could stay all night, and I said she could.

After awhile she said all the people in the house looked crazy, and

she was afraid of them. Then she would not go to bed, but sat up all

the night.”

“Had she any money?”

Ten Days in a Mad-House

“Yes,” I replied, answering for her, “I paid her for everything, and

the eating was the worst I ever tried.”

There was a general smile at this, and some murmurs of “She’s not

so crazy on the food question.”

“Poor child,” said Judge Duffy, “she is well dressed, and a lady. Her

English is perfect, and I would stake everything on her being a good

girl. I am positive she is somebody’s darling.”

At this announcement everybody laughed, and I put my

handkerchief over my face and endeavored to choke the laughter

that threatened to spoil my plans, in despite of my resolutions.

“I mean she is some woman’s darling,” hastily amended the judge.

“I am sure some one is searching for her. Poor girl, I will be good to

her, for she looks like my sister, who is dead.”

There was a hush for a moment after this announcement, and the

officers glanced at me more kindly, while I silently blessed the kind-

hearted judge, and hoped that any poor creatures who might be

afflicted as I pretended to be should have as kindly a man to deal with as Judge Duffy.

“I wish the reporters were here,” he said at last. “They would be able

to find out something about her.”

I got very much frightened at this, for if there is any one who can

ferret out a mystery it is a reporter. I felt that I would rather face a

mass of expert doctors, policemen, and detectives than two bright

specimens of my craft, so I said:

“I don’t see why all this is needed to help me find my trunks. These

men are impudent, and I do not want to be stared at. I will go away.

I don’t want to stay here.”

So saying, I pulled down my veil and secretly hoped the reporters

would be detained elsewhere until I was sent to the asylum.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

“I don’t know what to do with the poor child,” said the worried

judge. “She must be taken care of.”

“Send her to the Island,” suggested one of the officers.

“Oh, don’t!” said Mrs. Stanard, in evident alarm. “Don’t! She is a

lady and it would kill her to be put on the Island.”

For once I felt like shaking the good woman. To think the Island was

just the place I wanted to reach and here she was trying to keep me

from going there! It was very kind of her, but rather provoking

under the circumstances.

“There has been some foul work here,” said the judge. “I believe this

child has been drugged and brought to this city. Make out the papers

and we will send her to Bellevue for examination. Probably in a few

days the effect of the drug will pass off and she will be able to tell us

a story that will be startling. If the reporters would only come!”

I dreaded them, so I said something about not wishing to stay there

any longer to be gazed at. Judge Duffy then told Policeman Bockert

to take me to the back office. After we were seated there Judge Duffy

came in and asked me if my home was in Cuba.

“Yes,” I replied, with a smile. “How did you know?”

“Oh, I knew it, my dear. Now, tell me were was it? In what part of

Cuba?”

“On the hacienda,” I replied.

“Ah,” said the judge, “on a farm. Do you remember Havana?”

“Si, senor,” I answered; “it is near home. How did you know?”

“Oh, I knew all about it. Now, won’t you tell me the name of your

home?” he asked, persuasively.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

“That’s what I forget,” I answered, sadly. “I have a headache all the

time, and it makes me forget things. I don’t want them to trouble me.

Everybody is asking me questions, and it makes my head worse,”

and in truth it did.

“Well, no one shall trouble you any more. Sit down here and rest

awhile,” and the genial judge left me alone with Mrs. Stanard.

Just then an officer came in with a reporter. I was so frightened, and

thought I would be recognized as a journalist, so I turned my head

away and said, “I don’t want to see any reporters; I will not see any;

the judge said I was not to be troubled.”

“Well, there is no insanity in that,” said the man who had brought

the reporter, and together they left the room. Once again I had a fit of

fear. Had I gone too far in not wanting to see a reporter, and was my

sanity detected? If I had given the impression that I was sane, I was

determined to undo it, so I jumped up and ran back and forward

through the office, Mrs. Stanard clinging terrified to my arm.

“I won’t stay here; I want my trunks! Why do they bother me with so

many people?” and thus I kept on until the ambulance surgeon came

in, accompanied by the judge.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

CHAPTER V.

PRONOUNCED INSANE.

“HERE is a poor girl who has been drugged,” explained the judge.

“She looks like my sister, and any one can see she is a good girl. I am

interested in the child, and I would do as much for her as if she were

my own. I want you to be kind to her,” he said to the ambulance surgeon. Then, turning to Mrs. Stanard, he asked her if she could not

keep me for a few days until my case was inquired into. Fortunately,

she said she could not, because all the women at the Home were

afraid of me, and would leave if I were kept there. I was very much

afraid she would keep me if the pay was assured her, and so I said

something about the bad cooking and that I did not intend to go

back to the Home. Then came the examination; the doctor looked

clever and I had not one hope of deceiving him, but I determined to

keep up the farce.

“Put out your tongue,” he ordered, briskly.