Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (12 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

ı

Saray

ı

Topkap

ı

Saray

ı

, the Great Palace of the Osmanl

ı

Sultans, is the most extensive and fascinating monument of Ottoman civil architecture in existence. In addition to its architectural and historical interest, it contains, as a museum, superb and unrivalled collections of porcelains, armour, fabrics, jewels, illuminated manuscripts, calligraphy, and many objects of art formerly belonging to the sultans. A cursory visit requires several hours; to know it thoroughly many weeks would hardly suffice.

When Mehmet the Conqueror, known to the Turks as Fatih Sultan Mehmet, captured Constantinople in 1453, he found the former palaces of the Byzantine Emperors in such ruins as to be uninhabitable. He therefore selected a large overgrown area on the Third Hill as the site of his palace, the district where now stand the central buildings of the University of Istanbul and the great complex of the Süleymaniye. Here he erected an extensive palace which later came to be known as Eski Saray, or the Old Palace. For only a few years later, in 1459, he decided to build a new palace at the northern end of the First Hill; the area once occupied by the ancient acropolis of Byzantium. To do so he cut off the point of the Constantinopolitan triangle by building a massive defence-wall, guarded by towers, which extended from the Byzantine sea-walls along the Golden Horn to those along the Marmara. (The palace eventually took its name from the main sea-gate in these defence-walls; this was Topkap

ı

, the Cannon Gate, so-called because it bristled with armaments. This twin-towered gateway formerly stood at Saray Point, but it was destroyed in the nineteenth century.) The area thus enclosed must be approximately identical with the ancient city of Byzantium before its successive enlargements. Fatih Mehmet constructed his palace on the high ground, or acropolis; on the slopes of the hill and along the seashore he laid out extensive parks and gardens. He could not have chosen a more magnificent site in the city. As Evliya Çelebi remarked of it more than three centuries ago: “Never hath a more delightful residence been erected by the art of man.”

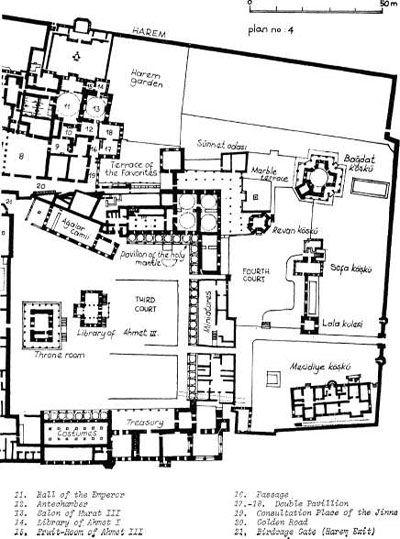

Of the Palace as we know it today, almost the entire plan, with the exception of the Harem and the so-called Fourth Court, was laid out and built by Fatih between 1459 and 1465. The Harem in its present state belongs largely to the time of Murat III (r. 1574–95), with extensive reconstructions and additions chiefly under Mehmet IV (r. 1648–87) and Osman III (r. 1754–7); while the isolated pavilions of the Fourth Court date from various periods. On three occasions, in 1574, 1665 and 1856, very serious fires devastated large sections of the Palace, so that while the three main courts have preserved essentially the arrangement given them by Fatih, many of the buildings have either disappeared (as most of those in the First Court) or been reconstructed and redecorated in later periods.

The Palace of Topkap

ı

must not be thought of merely as the private residence of the Sultan and his court, for it was much more than that. It was the seat of the supreme executive and judicial council of the Empire, the Divan, and it housed the largest and most select of the training schools for the imperial civil service, the Palace School. The various divisions of the Saray correspond pretty clearly with these various functions. The First Court, which was open to the public, was the service area for the Palace. It contained a hospital, a bakery, an arsenal, the mint and outer treasury, and a large number of storage places and dormitories for guards and domestics of the Outer Service, those whose duties did not ordinarily bring them into the private, residential areas of the Palace. The Second Court was the seat of the Divan, devoted to the public administration of the Empire; it could be entered by anyone who had business to transact with the Council. Beyond this court to right and left were certain other service areas: the kitchens and privy stables. The Third Court, strictly reserved for officials of the Court and Government, was largely given over to various divisions of the Palace School, but also contained some of the chambers of the selaml

ı

k, or reception rooms of the Sultan. The Harem, specifically the women’s quarter of the Palace, had additional rooms of the selaml

ı

k, the men’s quarter of the palace, and the Sultan’s private apartments, as well as quarters for the Black Eunuchs. The Fourth Court was a large enclosed garden on various levels with occasional pleasure domes. The total number of people permanently resident in the Saray was between 4,000 and 5,000.

THE FIRST COURT

The main entrance to the Palace, now as always, is through the Imperial Gate, Bab-

ı

Hümayun, opposite the north-east corner of Haghia Sophia and the fountain of Ahmet III (see Chapter 5). The great gatehouse is basically the work of Fatih Mehmet, though it has radically changed its appearance in the course of the centuries. Originally there was a second storey, demolished in 1867 when Abdül Aziz surrounded the gate with the present marble frame and lined the niches on either side with marble. The side niches were once used for the display of the severed heads of offenders of importance. The rooms in the gateway were for the Kap

ı

c

ı

s, or corps of guards, of whom 50 were perpetually on duty. The older part of the arch contains four beautiful inscriptions, one recording the erection of the gate by Mehmet the Conqueror in 1478, the other three quotations from the Kuran. The tu

ğ

ra, or imperial monogram, is that of Mahmut II, and other inscriptions record the remodelling by Abdül Aziz in 1867.

On entering through the Bab-

ı

Hümayun, we find ourselves in the First Court, often called the Courtyard of the Janissaries. On the right as one enters, there once stood the famous infirmary for the pages of the Palace School. Beyond this, a road leads down to the gardens of the outer palace, filled with Byzantine substructures and modern military installations. The rest of the right-hand side of that Court consists of a blank wall behind which were the palace bakeries, famous for the superfine white bread baked for the Sultan and the chosen few on whom he bestowed it; these buildings, several times burned down and reconstructed, now serve as workrooms for the museum.

On the left or west side of the Court, between the outer wall and the church of Haghia Eirene, once stood a quadrangle which housed the Straw Weavers and the Carriers of Silver Pitchers, and whose courtyard served as a storage place for the firewood of the Palace. Part of this has been excavated, revealing Byzantine substructures; these and the church of Haghia Eirene, converted by Fatih into an arsenal, are described in Chapter 5. North of the church, behind a high wall, are buildings once used as the Imperial Mint and the Outer Treasury. Beside these a road runs down to the museums and the public gardens of the Saray. The rest of this side of the Court was occupied by barracks for domestics of the Outer Service, a mosque, and storerooms; these, doubtless largely constructed of wood, have completely disappeared.

We now approach the Bab-üs Selam or Gate of Salutations, generally known as Orta Kap

ı

, or the Middle Gate. This is a much more impressive gateway than the first, very typical of the military architecture of Fatih’s time with its octagonal towers and conical tops. This was the entrance to the Inner Palace where everyone had to dismount, for no one but the Sultan was allowed to ride beyond this point. In the wall to the right of the gate is the Executioner’s Fountain (Cellat Çe

ş

mesi); here the executioner washed his hands and sword after a decapitation, which usually took place just outside the gate. Nearby are two Example Stones (Ibret Ta

ş

lar

ı

) for displaying the heads of important culprits. Here one comes to the public entrance to the Topkap

ı

Saray

ı

Museum where, after purchasing a ticket, one enters the Second Court.

THE SECOND COURT

This Court, still very much as it was when Fatih laid it out, is a tranquil cloister of imposing proportions, planted with venerable cypress trees; several fountains once adorned it and mild-eyed gazelles pastured on the glebe. Except for the rooms of the Divan and the Inner Treasury in the north-west corner there are no buildings in this court, which consists simply of blank walls faced by colonnaded porticoes with antique marble columns and Turkish capitals. Beyond the colonnade the whole of the eastern side is occupied by the kitchens of the palace, while beyond the western colonnade are the Privy Stables and the quarters of the Halberdiers-with-Tresses.

The Court of the Divan seems to have been designed essentially for the pageantry connected with the transaction of the public business of the Empire. Here four times a week the Divan, or Imperial Council, met to deliberate on administrative affairs or to discharge its judicial functions. On such occasions the whole courtyard was filled with a vast throng of magnificently dressed officials and the corps of Palace guards and Janissaries, at least 5,000 on ordinary days, but more than 10,000 when ambassadors were received or other extraordinary business was transacted. Even at such times an almost absolute silence reigned throughout the courtyard, a silence commented on with astonishment by the travellers who witnessed it.

The inside of the Bab-üs Selam has an elaborate but oddly irregular portico of ten columns with a widely overhanging roof, unfortunately badly repainted in the nineteenth century. To the right is a crude but useful bird’s-eye view of the Saray which helps one to get one’s bearings. The rooms on either side of the gate had various uses: guardrooms, the executioner’s room with a prison attached, waiting-rooms for ambassadors and others attending an audience with the Grand Vezir or Sultan.

From the gate, five paths radiate to various parts of the Court. Let us first visit – as is only right – the Divan. This, together with the Inner Treasury, projects from the north-west corner and is dominated by the square tower with a conical roof which is such a conspicuous feature of the Saray from many points in the city. This complex dates in essentials from Fatih’s time, though much altered at subsequent periods. The tower was lower in Fatih’s day and had a pyramidal roof, the present structure with its Corinthian columns having been added by Mahmut II in 1820.

The complex consists of the Council Chamber or Divan proper, the Public Records Office and the Office of the Grand Vezir. The first two open widely into one another by a great arch; each is square and domed. Both were redecorated in the time of Ahmet III in a rather charming rococo style, but the Council Chamber was restored in 1945 to its appearance in the reign of Murat III, who had restored it after the great fire of 1574. The lower walls are revetted in Iznik tiles of the best period, while the upper parts, the vaults and the dome, retain faded traces of their original arabesque painting. Around three sides of the room run low couch es covered with carpets. Here sat the members of the Council; the Grand Vezir in the centre opposite the door, the other Lords of Council on either side of him in strict order of rank. Over the Grand Vezir’s seat is a grilled window giving into a small room in the tower; here the sultans, after they had ceased to attend meetings of the Divan, could overhear the proceedings unseen. The Records Office has retained its eighteenth-century decor; here were kept records that might be needed at Council meetings. From here a door led to the Grand Vezir’s office, though the present entrance is from under the elaborate portico with richly painted rococo ceiling.

Adjacent to these three rooms is the Inner Treasury, a long room with eight domes in four pairs supported by three massive piers. Here and in the vaults below was stored the treasure of the Empire as it arrived from the provinces, and here it was kept until the quarterly pay-days for the use of the Council, the payment of officials, Janissaries and others; at the end of each quarter what remained unspent was transferred to the Imperial Treasury in the Third Court. In this room is now displayed the Saray’s collection of arms and armour. As one would expect, this is especially rich in Turkish armour of all periods, including much that belonged to the sultans themselves, and outstanding pieces of booty from foreign conquests in Europe, Asia and Africa.