Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (7 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

CA

Ğ

ALO

Ğ

LU HAMAMI

About half a kilometre along, we come on our left to Hilaliahmer Caddesi. If we follow this for about 100 metres, we see on our left the entrance to one of the most famous and beautiful public baths in Istanbul. This is the Ca

ğ

alo

ğ

lu Hamam

ı

, built in 1741 by Sultan Mahmut I. In Ottoman times the revenues from this bath were used to pay for the upkeep of the library which Sultan Mahmut built in Haghia Sophia, an illustration of the interdependence of these old pious foundations. There are well over a hundred Ottoman hamams in Istanbul, which tells us something of the important part which they played in the life of the city. Since only the very wealthiest Ottoman homes were equipped with private baths, the vast majority of Stamboullus for centuries used the hamams of the city to cleanse and purify themselves. For many of the poorer people of modern Istanbul the hamam is still the only place where they can bathe.

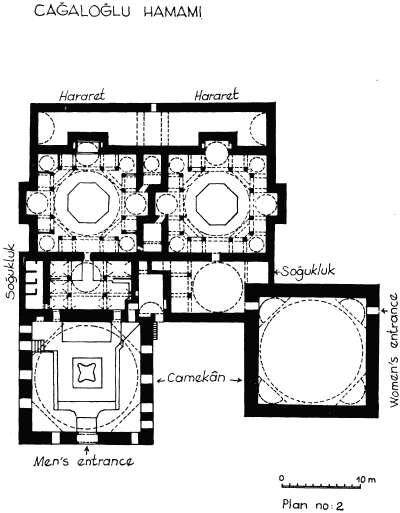

Turkish hamams are the direct descendants of the baths of ancient Rome and are built to the same general plan. Ordinarily, a hamam has three distinct sections. The first is the camekân, the Roman apoditarium, which is used as a reception and dressing room, and where one recovers and relaxes after the bath. Next comes the so

ğ

ukluk, or tepidarium, a chamber of intermediate temperature which serves as an ante-room to the bath, keeping the cold air out on one side and the hot air in on the other. Finally there is the hararet, or steam-room, anciently called the calidarium. In Turkish baths the first of these areas, the camekân, is the most monumental. It is typically a vast square room covered by a dome on pendentives or conches, with an elaborate fountain in the centre; around the walls is a raised platform where the bathers undress and leave their clothes. The so

ğ

ukluk is almost always a mere passageway, which usually contains the lavatories. In Ca

ğ

alo

ğ

lu, as in most hamams, the most elaborate chamber is the hararet. Here there is an open cruciform area, with a central dome supported by a circlet of columns and with domed side-chambers in the arms of the cross. In the centre there is a large marble platform, the göbekta

ş

ı

, or belly-stone, which is heated from the furnace room below. The patrons lie on the belly-stone to sweat and be massaged before bathing at one of the wall-fountains in the side-chambers. The light in the hararet is dim and shimmering, diffusing down through the steam from the constellation of little glass windows in the dome. Lying on the hot belly-stone, under the glittering dome, and lazily observing the mists of vapour condensing into pearls of moisture on the marble columns, one has the voluptuous feeling of being in an undersea palace, in which everyone is his own sultan.

Ca

ğ

alo

ğ

lu, like many of the larger hamams in Istanbul, is a double bath, with separate establishments for men and women. In the smaller hamams there is but a single bath and the two sexes are assigned different days for their use. In the days of old Stamboul, when Muslim women were more sequestered than they are now, the hamam was the one place where they could meet and exchange news and gossip. Even in modern Istanbul the weekly visit to the hamam is often the high point of feminine social life among the lower classes. And we are told by our lady friends that the women of Stamboul still sing and dance for one another in the hararet – another old Osmanl

ı

custom.

Leaving the Ca

ğ

alo

ğ

lu Hamam

ı

, presumably cleansed and purified, we continue on along Hilaliahmer Caddesi for another 100 metres and then turn left on Alay Kö

ş

kü Caddesi. About 100 metres along we come on our left to a small mosque with an elegant sebil at the street corner. This mosque and its külliye were built in 1745 by Be

ş

ir A

ğ

a, Chief of the Black Eunuchs in the reign of Sultan Mahmut I. In addition to the mosque and sebil, the külliye of Be

ş

ir A

ğ

a includes a library, a medrese and a tekke, or dervish monastery. The tekke is no longer occupied by dervishes, of course, since their various orders were banned in the early years of the Republic.

THE SUBLIME PORTE

A block beyond the mosque we come to Alemdar Caddesi, the avenue which skirts the outer wall of Topkap

ı

Saray

ı

. Just to the left at the intersection we see a large ornamental gateway with a projecting roof in the rococo style. This is the famous Sublime Porte, which in former days led to the palace and offices of the Grand Vezir, where from the middle of the seventeenth century onwards most of the business of the Ottoman Empire was transacted. Hence it came to stand for the Ottoman government itself, and ambassadors were accredited to the Sublime Porte rather than to Turkey, just as to this day ambassadors to England are accredited to the Court of St. James. The present gateway, in which it is hard to discover anything of the sublime, was built about 1843 and now leads to the various buildings of the Vilayet, the government of the Province of Istanbul. The only structure of any interest within the precinct stands in a corner to the right of the gateway. This is the dershane, or lecture-hall of an ancient medrese; dated 1565, it is a pretty little building in the classical style of that period.

Opposite the Sublime Porte, in an angle of the palace wall, is a large polygonal gazebo. This is the Alay Kö

ş

kü, the Review or Parade Pavilion, from whose latticed windows the Sultan could observe the comings and goings at the palace of his Grand Vezir. One sultan, Crazy Ibrahim, was said to have used it as a vantage point from which to pick off passing pedestrians with his crossbow. The present kiosk dates only from 1819, when it was rebuilt by Sultan Mahmut II, but there had been a Review Pavilion at this point from much earlier times. From here the Sultan reviewed the great official parades which took place from time to time. The liveliest and most colourful of these was the Procession of the Guilds, a kind of peripatetic census of the trade and commerce of the city which was held every half-century or so. The last of these processions was held in the year 1769, during the reign of Sultan Mustafa II.

It might be worthwhile to pause for a few moments at this historic place to read a description of one of these processions, for it reveals to us something of what Stamboul life was like three centuries ago. This account is contained in the

Seyahatname

, or

Book of Travels

, written in the mid-seventeenth century by Evliya Çelebi, one of the great characters of old Ottoman Stamboul. Evliya, describing the Procession of the Guilds which took place in the year 1638, during the reign of Sultan Murat IV, tells us that it was an assembly “of all the guilds and professions existing within the jurisdiction of the four Mollas (Judges) of Constantinople,” and that “the procession began its march at dawn and continued till sunset... on account of which all trade and work in Constantinople was disrupted for a period of three days. During this time the riot and confusion filled the town to a degree which is not to be expressed by language, and which I, poor Evliya, only dared to describe.”

Evliya tells us that the procession was distributed into 57 sections and consisted of 1,001 guilds. Representatives of each of these guilds paraded in their characteristic costumes or uniforms, exhibiting on floats their various enterprises, trying to outdo one another in amusing or amazing the crowd. The liveliest of the displays would seem to have been that of the Captains of the White Sea (the Mediterranean), who had floats with ships mounted on them, in which, according to Evliya, “are seen the finest cabin-boys dressed in gold, doing service to their masters who make free with drinking. Music is played on all sides, the masts and oars are adorned with pearls, the sails are of rich stuffs and embroidered muslin. Arrived at the Alay Kö

ş

kü they meet five or ten ships of the Infidels with whom they engage in battle in the presence of the Emperor. Thus the show of a fight is represented with the roaring of cannons, the smoke covering the sky. At last, the Moslems becoming victors, they board the enemy ships, take booty and chase the fine Frank boys, carrying them off from the old bearded Infidels, whom they put in chains, upset the crosses of their flags, dragging them astern of their ships, crying out the universal Moslem shout, Allah!, Allah!”

Besides the respectable tradesmen, artisans and craftsmen of the city, the procession included less savoury groups such as, according to Evliya, “the corporation of thieves and footpads who might be here mentioned as a very numerous one and who have an eye to our purses. But far be they from us. These thieves pay tribute to the two chief officers of the police and get their subsistence by cheating foreigners.”

The last guild in the procession was that of the tavern keepers. Evliya tells us that there were “one thousand such places of misrule, kept by Greeks, Armenians and Jews. In the procession wine is not produced openly, but the inn-keepers pass all in disguise and clad in armour. The boys of the taverns, all shameless drunkards, and all the partisans of wine pass, singing songs, tumbling down and rising again.” The last of all to pass were the Jewish tavern keepers, “all masked and wearing the most precious dresses... bedecked with jewels, carrying in their hands crystal and porcelain cups, out of which they pour sherbet instead of wine for the spectators.”

Evliya then ends his account by stating: “Nowhere else has such a procession been seen or shall be seen. It could only be carried into effect by the imperial orders of Sultan Murat IV. Such is the crowd and population of that great capital, Constantinople, which may God guard from all celestial and earthly mischief and let her be inhabited till the end of the world.” But the last procession of the guilds passed by more than two centuries ago, and the Alay Kö

ş

kü now looks down upon a drab and colourless avenue. Nevertheless, the guilds and professions which Evliya so vividly described are still to be seen in the various quarters of the town, looking and behaving much as they did when they passed the Alay Kö

ş

kü in the reign of Murat IV.

ZEYNEP SULTAN CAM

İİ

Following the Saray wall to the right of the Alay Kö

ş

kü we soon come to So

ğ

uk Çe

ş

me Kap

ı

s

ı

, the Gate of the Cold Fountain, which leads to the public gardens of Topkap

ı

Saray

ı

and to the Archaeological Museum. After passing the gate, we continue to follow Alemdar Caddesi, which now bends to the right, leaving the Saray walls. Just around the bend, on the right side of the avenue, we come upon a small baroque mosque, Zeynep Sultan Camii. This mosque was erected in 1769 by the Princess Zeynep, daughter of Ahmet III, and is a rather pleasant and original example of Turkish baroque. In form it is merely a small square room covered by a dome, with a square projecting apse to the east and a porch with five bays to the west. The mosque looks rather like a Byzantine church, partly from being built in courses of stone and brick, but more so because of its very Byzantine dome, for the cornice of the dome undulates to follow the extrados of the round-arched windows, a pretty arrangement generally used in Byzantine churches but hardly ever in Turkish mosques. The little sibyan mektebi at the corner just beyond the mosque is part of the foundation and appears to be still in use as a primary school. The elaborate rococo sebil outside the gate to the mosque garden does not belong to Zeynep’s foundation, but was built by Abdül Hamit I in 1778 as part of the külliye which we passed earlier. The sebil was moved here some years ago when the street past Abdül Hamit’s türbe was widened.