Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (47 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

Tomb A

, the first in the north wall, though it has lost its identifying inscription, is almost certainly that of Theodore Metochites himself; it has an elaborately carved and decorated archivolt above.Tomb B

is entirely bare.Tomb C

has well preserved paintings of a man and woman in princely dress but has lost it inscription.Tomb D

is that of Michael Tornikes, general and friend of Metochites, identified by the long inscription above the archivolt, which is even more elaborately carved than that of Metochites himself; fragments of mosaic and painting still exist.Tomb E

, in the fifth bay of the outer narthex, is that of the princess Eirene Raoulaina Palaeologina, a connection by marriage of Metochites. It preserves a good deal of its fresco painting.Tomb F

, in the fourth bay of the outer narthex, is that of a member of the imperial Palaeologus family but cannot be more definitely identified, though it preserves some vivid painting of clothes.Tomb G

, in the second bay of the outer narthex, is the latest in the church, probably not long before the Turkish Conquest; the painting shows strong influence of the Italian Renaissance, but the owner cannot be identified.Tomb H

, in the north wall of the inner narthex, is that of the Despot Demetrius Doukas Angelus Palaeologus, and has an inscription to the following effect: “Tou art the Fount of Life, Mother of God the Word and I Demetrius am thy slave in love.”

Before we leave Kariye Camii, we might pause for a moment before the portrait of Theodore Metochites, the man to whom we owe this church and its magnificent works of art. Seeing him there over the door leading into the nave of his church, proud and at the very peak of his career, we are saddened to learn that Theodore fell from royal favour in his later years. After Andronicus III usurped the throne in 1328, Theodore was stripped of his power and possessions and thrown into prison, along with many other officials of the old regime. Only when his life was drawing to a close was he freed and allowed to retire to the monastery of St. Saviour in Chora. He died there on 13 March 1331 and was buried in the parecclesion of his beloved church. In those last sad days of his life, Theodore was comforted by his friend, the great scholar Nicephorus Gregoras, who was also confined to the monastery. When Nicephorus later recorded the history of those times, he wote this affectionate tribute to Theodore: “From morning to evening he was most wholly and eagerly devoted to public affairs as if scholarship was absolutely indifferent to him; but later in the evening, having left the palace, he became absorbed in science to such a degree as if he were a scholar with absolutely no connection with any other affairs.” Theodore was the greatest man of his time, a diplomat and high government official, theologian, philosopher, historian, astronomer, poet and patron of the arts, the leader of the artistic and intellectual renaissance of late Byzantium. But among all his accomplishments, Theodore was proudest of the church that he had built and adorned. Towards the end of his life he wrote of his hope that it would secure for him “a glorious memory among posterity to the end of the world.” It has indeed.

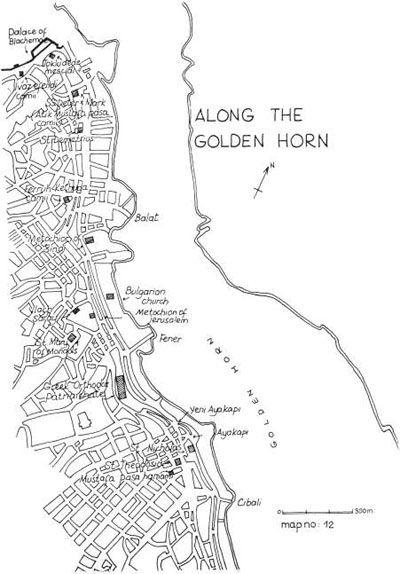

Golden Horn

The region along the Stamboul shore of the Golden Horn above the two bridges is one which few tourists ever see, except for one or two of the more famous monuments. This is a pity, for it has a distinctive atmosphere which is quite unlike that of any other part of the city. Some of its quarters, particularly Fener and Balat, are very picturesque and preserves aspects of the life of old Stamboul which have all but vanished elsewhere.

Our tour begins at the Stamboul end of the Atatürk Bridge. This is the place known as Odun Kap

ı

s

ı

, the Wood Gate, after a long vanished gateway known in antiquity as the Porta Plarea. The first part of our tour takes us along the shore highway, which is now bordered by a park along the Golden Horn, making our stroll easier and more pleasant than it was in times past.

GOLDEN HORN SEA-WALLS

As we walk along we see on the left side of the avenue stretches of the medieval Byzantine sea-walls that once extended along the shores of the Golden Horn and the Marmara, joining up with the land-walls at both ends. The stretch that we will pass on our present tour, which goes beyond what was once the end-point of Constantine’s wall, was originally built by Theodosius II in the fifth century to meet the great land-walls which he constructed at that time. These sea-walls were repaired and reconstructed many times across the centuries, particularly by the Emperor Theophilus in the ninth century. These fortifications consisted for the most part of a single line of walls ten metres in height and five kilometres long, studded by a total of 110 defence towers placed at regular intervals. Considerable stretches of this wall still remain standing, particularly along the route of our present tour, although almost all of it is in ruins. Much of this ruination was brought about in the last great sieges of the city, by the Crusaders in 1203–4 and the Turks in 1453. In both instances the besiegers lined up their warships against the sea-walls along the Golden Horn and repeatedly assaulted them. And the destruction wrought by these sieges and subsequent centuries of decay is now being rapidly completed by the encroachment of modern highways and factories.

The sea-walls along the Golden Horn were pierced by about a score of gates and posterns, many of them famous in the history of the city. Of these only one or two remain, although the location of the others can easily be determined, since the streets of the modern town still converge to where these ancient gates once opened, following the same routes they have for many centuries past. The first of these gates which we pass on our tour is about 450 metres along from the Atatürk Bridge. This is Cibali Kap

ı

, known in Byzantium as the Porta Puteae. A Turkish inscription beside the gate commemorates the fact that it was breached on 29 May 1453, the day on which Constantinople fell to the Turks. This gate also marks the point which stood opposite the extreme left wing of the Venetian fleet in their final assault on 12 April 1204.

The huge building along the side of the avenue before Cibali Kap

ı

is Kad

ı

r Has University. This private Turkish university, founded in 2002, is housed in the former Cibali Tobacco and Cigarette Factory, which opened in 1884. The factory was designed by Alexandre Vallaury and built by the architect Hovsep Aznavur. The factory was long disused before it was superbly restored and converted into a university. During the restoration an early Byzantine cistern was discovered beyond the end of the building near Cibali Kap

ı

.

About 250 metres past Cibali Kap

ı

we come on the left to a little pink-walled Greek church dedicated to St. Nicholas. This church dates to about 1720 and was originally the

metochion

, or private property, of the Vathopedi Monastery on Mount Athos. The corbelled stone structure in which the church is housed is typical of the so-called meta-Byzantine buildings we will see along the shore of the Golden Horn, most of them dating from the seventeenth or eighteenth century. The principal treasure of the church is a very rare portative mosaic dating from the eleventh century; it can be seen only during the services on Sunday. Notice also in the lobby the model of an ancient galleon hanging from the ceiling. These are to be found in many of the waterfront churches of the city, placed there by sailors in gratitude for salvation from the perils of the sea.

Just beyond St. Nicholas we come to Aya Kap

ı

, the Holy Gate, a little portal which opens from a tiny square beside the avenue. This was known in Byzantium as the Gate of St. Theodosia, after the nearby church of the same name.

CHURCH OF ST. THEODOS

İ

A

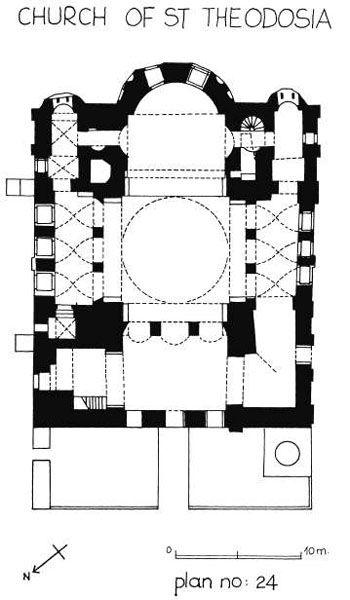

To reach the church we pass through the gate and continue for about 50 metres until we come to the second turning on the left, where we continue for another 50 metres until we come to Gül Camii, somewhat doubtfully identified as the Church of St. Theodosia. Its history is obscure but the foundations recently brought to light date from the late tenth or the eleventh century, as is shown by the “recessed brickwork” typical of this period. Thus the earlier dating of the church to the ninth century appears to be erroneous.

The building is one of the most imposing Byzantine churches in the city and, in spite of a certain amount of Turkish reconstruction, still preserves its original form. It is a cross-domed church with side aisles supporting galleries; the piers supporting the dome are disengaged from the walls, and the corners behind them form alcoves of two storeys. The central dome and the pointed arches which support it are Turkish reconstructions, as are most of the windows. From the exterior the building is rather gaunt and tall: the upper parts have been considerably altered in Turkish times, with the result of making it still more fortress-like. The two side apses, however, are worthy of note, with their three tiers of blind niches and their elaborate brick corbels. Among the more pleasing aspects of the exterior is the minaret, handsomely proportioned and clearly belonging to the classical period when the church was converted into a mosque.

There are two interesting legends associated with the church: one of them perhaps true, the other almost certainly false. The first of these legends (the one which may be true) concerns the Turkish name of the building, Gül Camii, or the Mosque of the Rose. It seems that the saint’s feast-day falls on 29 May, and on that day in the year 1453 a great congregation assembled in the church appealing for Theodosia’s intercession. The church had been decked with roses in celebration of the feast-day, and when the Turkish soldiers entered the church after the city fell they found the roses still in place: so the romantic story goes, and hence the romantic name.

The second legend, which seems to have originated long after the Conquest, has it that the church of St. Theodosia was the final resting-place of Constantine XI Dragases, the last Emperor of Byzantium. There are several different traditions as to the circumstances of the Emperors death and the place of his burial, but the one in favour among Greeks of an older generation was that he was interred in a chamber in the south-east pier of St. Theodosia. And indeed there is a burial-chamber there, reached by a staircase leading up inside the pier itself, and within it is a coffin, or sarcophagus, covered by a green shawl. However, an equally persistent Turkish legend has it that this is not the tomb of Constantine but that of a Muslim saint called Gül Baba, the eponymous founder of the mosque! To further complicate the problem, above the lintel of the door leading to the burial-chamber there is a cryptic Turkish inscription which reads: “Tomb of the Apostle, disciple of Christ, peace be to him.”