Stars of David (50 page)

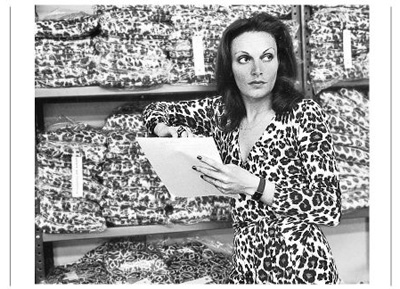

Diane von Furstenberg

DIANE VON FURSTENBERG PHOTOGRAPHED IN 1974 BY JILL KREMENTZ

IN ALL HER YEARS in the spotlight as a successful fashion designer, arbiter of style, and chic fixture of New York night life, Diane von Furstenberg never publicly discussed the fact that her mother was a Holocaust survivor. And she wasn't prepared to change that when she walked to the podium at an Anti-Defamation League event in 1981 to receive their Woman of Achievement Award.

“I had just gotten back from Bali,” she says, dressed in a leather jacket in her plush office that feels more like a boudoir with its pink walls and electic art.

The morning of the ADL benefit, von Furstenberg called her assistant. “I said, âOh my God, do I have to do this?' And she said, âYes, these women are your customers.' I had no idea what the Anti-Defamation League was, only that they had decided to honor me. And it's only when I started to thank them at the podium that it all just came to me; I found myself saying, âEighteen months before I was born, my mother was in Auschwitz.' To hear myself say that was a revelation to me. That's when I realized that I had somewhat of an obligation to talk about it.”

She also decided to write about it. In her memoir,

Diane: A Signature

Life

, she described her mother, Lily Nahmias, who in 1945 at the age of twenty-one was freed from the Neustadt-Glewe concentration camp. “My mother rarely talked about the camps during my childhood in Brussels,” she wrote. “I remember the numbers that were tattooed on her arm from two of the three camps she had been in, but after a while she had the tattoos removed because it annoyed her to have people constantly remark on them.”

“I would hear her talk about her experience when I was growing up,” says von Furstenberg now, shifting in her black suede pants on her leather sofa. “It was always there. But to me, she would only talk about the good things: the camaraderie; only the good things.”

I ask von Furstenberg if she had a sense of being Jewish growing up. “Not at all,” she says as she shakes her head firmly. “Because I was born too close to the war.” Her point is that survivors like her mother often disengaged from Judaism after their horrific experience. “It was never something I addressed at all.”

Still, she writes in her book, “The Holocaust has shaped my character from inception.” I read her that quote. “Well yes,” she says. “It's very much who I was. My mother was a total miracle. She weighed forty-nine pounds at the end of the war, she was not supposed to be alive; but she did make it, she survived, she married my father. She wasn't supposed to have a child, but I was born healthy eighteen months later . . . a total miracle. Everybody comes with a certain DNA; that was my DNA. So my responsibility or duty or thankfulness means that I have to take that energy and live it. And be thankful for it. So yes, I do think that it makes me very much who I am.”

Her mother told her one story as a child which became a defining parable for the way to live life. On the train to the camp, her mother befriended an older woman who offered much-needed maternal comfort. When the Nazi guards eventually separated prisoners into two lines, Lily Nahmias clung to her new older friend. But an officer forced the women apart despite Lily's protestations; her friend went into a separate line. As it happened, the group Lily was desperate to join was sent to the gas chamber, while she was spared. “From this sad event,” von Furstenberg writes, “my mother drew the life lesson that you never really know what's good for you. What may seem to be the absolute worst thing to happen to you can in fact be the best.”

“It's a story that I always heard,” she explains now, “and it's a very strong story. It didn't traumatize me. But it is a story that I use a lot when people complain. I say, âYou know what? You never know.'”

Von Furstenberg, born Diane Simone Michelle Halfin in Brussels on December 31, 1946, absorbed her mother's resilience and clearly has drawn on it repeatedlyâduring the divorce from her first husband, Prince Egon von Furstenberg, when her business plummeted in the 1980s, when she was diagnosed with tongue cancer in 1994. “Whatever happens, my mother always told me, you just deal with it and turn it around. There's not even an alternative. There's always something good. The one thing that I think is most valuable that she taught me is that fear is

not

an option. She would just never allow me to be afraid, and as a result, I was never afraid. It's the best gift she could have given me.”

After the ADL honor, von Furstenberg became very involved in fund-raising for the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., and invited her mother and two children, Alexandre and Tatiana, then twenty-three and twenty-two respectively, to join her at the opening in April 1993. I assume the visit must have been emotional. “Well, we made it very light and we turned it into a field trip. I went with my kids. I didn't want it to be heavy.”

She writes more expansively about accompanying her mother into the new museum: “I held her small hand tightly as we walked quickly through the original gate of Auschwitz with its sign: ARBEIT MACHT FREI (âWork makes one free'). I did not want her to break down. The four of us were silent as we walked through the museum, keeping our feelings under control. My mother's example had taught us not to give in to sorrow . . .”

She says now that, in its way, this particular evening felt like a victory: “There we were, the four of us, and for my mother it obviously meant so much; she had survived, she was there with her daughter and grandchildren. It's only afterwards when we came back that I know it affected her, and for a few days, it affected me too.”

The intercom in her office suddenly blares, “

Diane?

”

She calls out, “Yes?”

“Libby from

Inside Story

wants to confirm the interview with you tomorrow at six?”

Von Furstenberg goes to check her calendar on her desk, which sits in front of her Warhol portraits, and checks her calendar. “That's right,” she affirms.

It's the holiday season and the flurry of orders and sample sale preparations can be felt even in this third-floor oasis above the design studio.

I ask von Furstenberg if she raised her children with any religion. “No,” she replies. “My children were actually christened because of my husband. But I don't like religion. I think it's destructive. I believe in God. I have my own personal relationship with God.” She goes to synagogue once a year. “Yom Kippur is something I do

alone

, with nobody else, because I believe that my relationship with God is mine and mine only. And I do fast. I do that.”

Her marriage in July 1969 to Prince Eduard Egon von und zu Furstenbergâwho hailed from the Agnelli family, which owned Fiatâ was somewhat controversial. “They didn't like that I was Jewish,” she says of Egon's relatives, “but my husband didn't care.” Egon's father attended their wedding ceremony but refused to go to the reception. Did that trouble her? She shrugs. “I felt bad for him. I didn't feel bad for me.”

She is a proponent of intermarriage across all backgrounds. “I think the more people mix, the better we are,” she says. “It's better for the blood, people look better. I like that.”

Her phone is ringing, the intercom is buzzing, and I realize I have to let her get back to work. As she walks me out, I ask how she'd respond if someone asked her what religion she is.

Von Furstenberg pauses a moment. “I'd say I was born of Jewish parents,” she says, “and I'm Jewish. But I don't like religion. There are a lot of things about the Jewish faith that I like; what I like the most is that you're responsible for yourself. You take your life in your hands and you're responsible for your actions. There are a lot of things that I like about it . . . I do carry and honor the strength of my mother. I'm thankful that she was saved. And I want to be buried as a Jew; very simply.”

Acknowledgments

TO ALL THOSE PEOPLE WHOSE HELP AND ENCOURAGEMENT WERE INCALCULABLE: Dan Algrant, Jamie Alter, Lisa Belzberg, John Bennett, Candice Bergen, Jeremy Coleman, Marcia DeSanctis, Nick Dolin, Rachel Dretzin, Noah Emmerich, Marshall Goldberg, Jane Harnick, David Holbrooke, the Jordan family, Esther Kartiganer, Billy Kingsland, Deborah Kogan, Edward Klaris, Lorin Klaris, Itamar Kubovy, Rabbi Irwin Kula, Al and Lori Leiter, Miranda Levenstein, Tom Levine, Marvin Levy, Michael Lynton, Joshua Malina, Steve Nemeth, Kenneth Nova, Lucie Perry, Holly Peterson, Richard and Lisa Plepler, David Pogrebin, Christy Prunier, Michael Ravitch, Gretchen Craft Rubin, Ira Sachs, Dani Shapiro, the Shapiro family, Annie Silberman, Joshua Steiner, Alexandra Styron, Chris Taylor, Julie Warner, Pamela Weinberg, Phyllis Wender, Hanya Yanagihara.

Special thanks to:

JILL KREMENTZâfor her generosity and kindness

RABBI JEN KRAUSEâfor her teaching and uncomplicated friendship

LETTY COTTIN POGREBINâfor her tireless advice and constant example

BERT POGREBINâfor his unflagging enthusiasm

ROBIN POGREBINâfor her editorial counsel and for finding the title

DIANNE CHOIEâfor her diligence and good humor

DEB FUTTERâfor her astute guidance, gusto, and early faith

DAVID KUHNâfor his daily wisdom and extraordinary capacity to make things happen

Epilogue

A FUNNY THING HAPPENED on my way to finishing this book: I became more Jewish.

I'm not saying I now keep kosher or daven every morning. What I mean is that I've become more stirred by Judaismâmore impatient to understand it, more surprised by how preoccupying it is, less baffled by those who prioritize it. Judaism became a richer piece of my life.

Over the course of the last two years, as I listened to one prominent person after another describe how onerous Hebrew school was, how readily they left religion behind after their bar or bat mitzvah day, how boring they find synagogue, how unaffected they are by prayer, the more I felt drawn to understand the religion myself. The more I heard Jewishness described as a gut connection, a shared history, a value-system, a vibrant culture, but not in terms of ritual or liturgy, the more I felt pulled toward exactly those things: the scaffolding of this obstinate tradition.

During these many varied conversations, I never felt disapproving when someone told me they were indifferent to the religious aspects of being Jewish; on the contrary, I related to the sentiment. But it also made me want to investigate what so many people, including myself, had rejected or never opted to explore.

I trace this bend in the road, in large part, to Leon Wieseltier. I walked out of his Washington office at the

New Republic

feeling dazed and provoked. I took his rebuke of “slacker” Jews as a personal challenge: How could I make choices regarding my faith, let alone pass on a legacy to my children, when I knew so little about it? I'll never forget his response when I pointed out that for many of the people I'd interviewed, observance takes a lot of time out of already busy lives. “Oh please,” he'd scoffed. “We're talking about people who can make a million dollars in a morning, learn a backhand in a month, learn a foreign language in a summer, and build a summer house in a winter . . . We're talking about intelligent, energetic individuals who master many things when they wish to.”

I know I can never hope to make a million dollars in a morning, but I also know I manage to make time for things that count. I schedule my life around my son's baseball game, my daughter's art class, a particular yoga instructor. When Wieseltier said, “It's all about what's important to you. It's about motivation and will,” I felt the proverbial lightbulb go off over my head: “You should make time for this,” I told myself.

So I started studying Torah. Every Thursday morning, a young rabbi named Jen Krauseâa brainy, spirited, and blessedly unpretentious teacherâmet with me and a friend over coffee and for ninety minutes we dissected the Torah portion of the week. The process was demanding and emboldening, not just because I grasped the Jewish chronicle in its entirety for the first time, but because I realized that simply reading the story of the Jewish people was the key to the club. Keeping up with each week's chapterâbeing guided by a scholar and discussing it with a friendâwas my entrée into a world that had long felt closed and overwhelming. Suddenly, I had a place at the table, and no question was too simple or sacrilegious. I realized I was entitled to this narrative, tooâit was mine as much as anyone else'sâand by wrestling with the text, I watched it come alive. What I'd assumed would be heavy lifting (an assumption that had kept me from taking any first step) wasn't arduous at all.

I discovered for myself why the Bible narrative endures: how each chapter is packed with upheaval and spectacle, how every verse can launch a conversation, why there's so much room for disagreement. I'm sure veterans of Torah study will roll their eyes at my elementary Eureka!, but the juiciness of the text was, frankly, news to me. The missteps of the patriarchs and matriarchs were also resonant; it was instructive to look at ancient self-interest and selflessness with a contemporary eye.

When the Passover holiday arrived, I actually felt equipped to tell my kids the Exodus story. I went to the West Side Judaica store and bought a “Bag O' Plagues,” which included a plastic locust (God sent pestilence as one penalty for Pharaoh's intransigence) and a frog that hops (God also sent a barrage of frogs). I prepared a playlet for the family seder, with my nephew playing Moses, my son Pharaoh, and my daughter and niece Israelite slaves lugging fake bricks in the desert. As we rehearsed, minutes before the seder began, my brother-in-law's seven-year-old niece announced she wanted to join in. Inspired by her red tights, I assigned her the role of the Red Sea. When she parted her knees for Moses' passage to freedom, relatives rolled with laughter, and I realized we should probably find a more G-rated simulation next time.

When the High Holy Days arrived the following autumn, I found myself volunteering to run the children's services for our congregation in Connecticut. As I spent weeks designing the kind of ceremony I'd been trying for years to find for my own kids at other synagogues, I became a bit obsessed. I pored over Internet High Holy Days lessons, ordered twenty plastic shofars online for the kids to blow, found painted wooden apples for the children to pretend to “slice,” and purchased every Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur storybook listed on

Amazon.com

. When I couldn't find a children's song that explained the holiday in fundamental terms, I wrote one: “The Sorry Song,” so named because the theme of the holidays is atonement. (“Oops, I had a tantrum. Oops, I threw my food. Oops, I didn't listen to my parents and was rude.” You get the idea.) The kids ended up learning the lyrics with my rudimentary guitar accompaniment, and after children's services we were invited to sing my new composition for the entire congregation.

At the Kol Nidre service, I was given the honor of opening the Torah ark. It didn't matter that the ark in our provisional temple is pint-sized; I was trembling when I wrapped a tallis around my shoulders for the first time in my life and approached the bimah.

I RSVP'd

yes

for the first time to a Sukkoth gathering one week after Yom Kippur. I'd never helped build a sukkah before, let alone eaten under one, and two years earlier the idea of devoting a Saturday morning to that enterprise would have been unthinkable. But there I was, feeling choked up as I watched my children take the

lulav

(branches) and

etrog

(citron) that were passed around and shaking them toward the four corners of the world.

I started reading my son a chapter from the

Children's Illustrated Jewish

Bible

(foreword by Rabbi Joseph Potasnik) each night. Its compact, dramatic storytelling and stormy illustrations are perfect for a second-grader. Ben is riveted by the stories, and I'm not surprised: Few other children's chapter books are as action-packed. What novel offers an evil serpent, a deadly flood, brother killing brother, father sacrificing son, son tricking father, stone spouting water? I'm glad to see that Ben is turned on by the Bible, but I'm also a little relieved:

This isn't medicine

, I think to myselfâ

he

likes it

. This is a road we can take together. Where it leads doesn't matter to meâonly that he and my daughter become engaged in the Jewish story soonerâand more naturallyâthan I did.

The final rung on this strange ladder was my decision to become bat mitzvahed when I turned forty last May. With Jen's help, I boned up on my hazy college Hebrew, learned the singsong melodies used to recite Torah, and prepared a brief talk about the Emor portion of Leviticus. I'm sure some of my friends thought I'd gone off the deep end, but for some reason this didn't strike me as extreme. It felt as if I'd been unwittingly headed toward this rite of passage, albeit at a glacial speed, for a long time.

When I first met the diplomat Richard Holbrooke, he asked me why I'd chosen this book topic, and I stumbled over an explanation, admitting that I myself was struggling with the same questions of identity that I was probing with famous Jews. “So this is therapy for you,” he said. “We're therapy.” I balked at his comment at the time. But maybe, in a roundabout way, he'd hit on something: I may not have consciously conceived this project to confront my own confusions, but it certainly has had that effect.

I started this book because I was genuinely curious about how being Jewishâthat unique amalgam of ritual, Israel, Holocaust, matzo, Torah, and Seinfeldâsits with people who live public lives, who are among America's success stories. But every person I spoke to made me look at myself: my childhood, my children, my marriage, my faith or lack of it, my education or ignorance, my connection or indifference. Every one of these conversations was a prick at my conscience. I personalized each person's story. And no matter the gulf in stature between us, each person felt fundamentally linked to me.

I realize this epilogue is personal: Even after talking to more than sixty Jews, I don't think it's my placeânor am I equippedâto make broad, authoritative summations. I could proclaim that most Jewish public figures aren't publicly Jewish; that most have abandoned customs, intermarried, or don't seem very worried about Jewish continuity; that all of them feel unshakable Jewish pride. But I don't know any of these things with any scientific or sociological certainty. What I do know is that being Jewish is powerful and, in a sense, unavoidableâwhether one embraces it or leaves it on the shelf, whether one lives a visible life or an anonymous one. And that, in the process of writing this book, it's become more vital to me than I ever expected.