Stars of David (45 page)

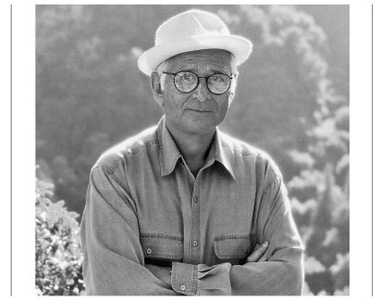

Norman Lear

ARCHIE BUNKER WAS A RACIST, sexist anti-Semite, but his creator, Norman Lear, reminds us he was all talk. “There was nothing violent about his attitudes about anything,” Lear says. “He was more fearful than anything else. I mean, he wouldn't light a cross on a lawn or be any part of that. But his invective would cover the landscape.”

Lear says there are too many instances in

All in the Family

's nine seasons on the air to recount the times Archie knocked the Jews, but in one episode, he needed a Jew: When Bunker feigned injury from a minor traffic accident in order to recover insurance, he wanted to hire a Jewish attorney to help him win. “He went to Rappaport, Rappaport, and Rappaport or something like that [it was actually Rabinowitz] because he wanted the smartest lawyer, so he wanted a Jew,” Lear recounts. “And of course, when the law firm sent somebody out to the house, the attorney was, from first blush, anything but Jewish. This lawyer explained to Archie that since his firm knew the neighborhood, they figured Archie couldn't be Jewish: âSo of course they sent me: I'm the house goy'” (a reference to the designated gentile who would turn the lights on and off for an Orthodox family during Sabbath).

Lear sits at a wooden table in his spacious Beverly Hills office, looking relaxed in a blue chambray shirt, vest, and rimless glasses. There is no overt evidence that this is the man who made $485 million when he sold his company in 1985 or that he fits a description from Chicago's Museum of Broadcasting Communications: “

No single individual has had more influence

through the medium of television in its 50-year history than Norman Lear

.” Despite a producing career that's spanned four decades and included iconic series such as

Sanford and Son, Maude, The Je fersons, Good Times,

and

Mary

Hartman, Mary Hartman

, plus some debacles along the way, he appears to be a very youthful, hearty eighty-two-year-old, perhaps by necessity: In addition to his three children and five grandchildren from his first two marriages, at the time we meet he now has eight-year-old twins and a fifteen-year-old son by his third wife, Lyn Davis.

“I was thrilled to see Benjamin bar mitzvahed,” he says of his teenager. “His mother's not Jewish, and I would not have insisted. It was

his

decision and that thrilled me. But I have no interest in the formal processes of the religion. When I infrequently go to a gospel service, I'm more comfortable there than I am in synagogue. I think Jewish services are stiff and dull and awkward.”

Lear grew up poor in Hartford, Connecticut; on Passover, his grandparents “came with their dishes” from New Haven. The Lears moved to a small apartment in Brooklyn just in time for his bar mitzvah celebration. “I remember a bathtub full of soft drinks and beer and ice,” Lear says with a smile. “And a bunch of fountain pens. And two-dollar bills.”

Lear says his brand of Judaism is social consciousness. “I will say this about my own Jewishness.” He leans forward. “I was inordinately aware of anti-Semitism in the world. I listened to Father [Charles] Coughlin on the air as a kidâI don't remember how old I was. And I listened to a fellow by the name of Carl MacIntyre out of New Jersey who was a Protestant Jew-hater. And I had a nose for anti-Semitism unlike any other.

People for

the American Way

came directly out of that nose.”

He's referring to the organization he started in 1981, which became an influential watchdog safeguarding constitutional freedoms. He founded this group after spending hours watching ministers Jimmy Swaggart, Jerry Falwell, and Pat Robertson on televisionâpreparation for a screenplay he was writing which, he says, was going to “savage” their profession. Lear recalls his revulsion watching these evangelists: “I thought, âNot in my America,'” he says. “âThis is really dangerous.' And so I decided to create a TV spotâa sixty-second commercial which ended with a fellow saying,

âThey can't tell you you're a good Christian or a bad Christian depending on your

political point of view: That is not the American way.'

So somebody suggested, âCall the organization “People for the American Way.” '” Lear chuckles. “I'm on sort of a rant here, but it all began out of this Jewish nose.”

That Jewish nose isn't sensing rampant anti-Semitism these days, but it's still wary. “While I feel absolutely at home and fully integrated in this country, history teaches that one's guard should be up,” Lear says. He is also watchful of the behavior of Israelis. “I remember the first time I started to read the word âhumiliation' in newspapers: âArabs being humiliated at roadblocks.' I know just enough about uniforms and humanity to know that, no matter who they are, some percentage of people in uniform will behave very badly. So there had to be some truth in those accusations of Israeli abuses from the beginning of the settlements. And to the extent that Jews caused humiliation, I was very upset.”

Lear makes it clear he thinks religious allegiances are obsolete; he has a vision of creating harmony via our television screens. “I think when the hardware, the technology becomes available, one of the most helpful things that could occurâby âhelpful' I mean to bring together races, religions, and so forthâwould be an international Sunday morning service. It would be closer to gospel, but it would be universal gospelâmusic from every discipline everywhere in the worldâwhich was all about that which unites the human of the species, not the stuff that divides us like, âI worship this way, you worship that way.'”

How would he square his proposed melding of religions with the joy he felt when his son chose to become a bar mitzvah? “It's not easy,” he concedes. “What I want to maintain are the memories of my grandmother Hannah Rachel and all the gorgeous little fresh-to-this country Jews. But you see it's only

my

memory; my kids don't have those memories. And you can't pass those on. They die with me. My memories of Friday nights with the spanking white tablecloth and the candles and so forth . . .” He trails off.

“We live at a time when, I don't know how many dozens of times in the course of a year, I'll have a conversation with my wife about how difficult it is to pull the family together in our

own

home. We have three kids: The twins are eight, Benjamin is fifteen. They are so bloody

busy

. It used to be just the

father

's late.” In other words, family togethernessâwhich he connects to Jewish scenes of his childhoodâmakes him want to keep certain rituals afloat. “I could cry remembering how my grandfather took an hour and a half for the Passover ceremony that used to bore the shit out of us,” he says with a laugh, “but now I reflect on it, how sweet it was.”

So he carries that tradition on, albeit without religious content. “At my seder this year, we did a reading of Justice Learned Hand's speech about liberty, and then we talked about how it applies to everything that's going on in the world,” he says. “It was the best seder service I can remember. My kids

got

it.” He pauses. “I realize that I haven't answered your question.” He has, in his way. It's what I've heard from so many: They reject Judaismâ and often religion in generalâbut they can't let go of feeling Jewish. “I'm sure others have expressed to you the enormous pride in the contributions the Jewish people have made anywhere one cares to look,” Lear says, “except perhaps ice hockey. But medicine, science, music,

comedy

âmy God.”

He says his proudest Jewish moment was watching his son hold the Torah, but other Jewish snapshots resonate, too. “Eating my grandmother's matzo balls. Just remembering her stooped over the oven and her soup . . . The smell.” His eyes water. “I cry easily. Jews are wet. I like that. There are wet people and dry people. Jews are wetter.”

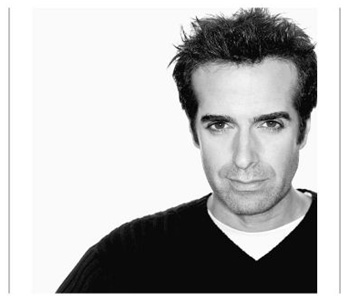

David Copperfield

DAVID COPPERFIELD, the nation's most successful magicianâwho has won nineteen Emmy awards, ranked number 43 on Forbes' Celebrity 100 list of 2003 (earning fifty-five million dollars), been knighted by the French government, waxed at Madame Tussaud's, and licked on postage stamps in four countriesâhas just asked his assistant to order him Kentucky Fried Chicken.

When I first arrived at Copperfield's high-rise apartment on a sweltering June day in New York City, his assistant opened the door and closed it almost as fast, telling me that the air-conditioning was out and the interview would take place across the hallway in the “Sky Terrace”âa private common room for tenants with wraparound views of the city. To my frustration, I'd stolen only a fleeting peek of Copperfield's foyer before the door closed; I glimpsed antique arcade games aglow in the darkness. (Copperfield collects and restores these toys.)

As I settle myself on a beige sofa in the earth-toned Sky Terrace, Copperfield pads in in bare feet, dressed in a spotless white Polo crew-neck sweatshirt and immaculate jeans. His polish, even in a casual setting, is consistent with his personality, at least the one he reveals to me: smooth, glib, chary.

I ask him to tell me about his Jewish upbringing.

“Ask me specific questions,” he instructs.

“Did your family celebrate all the Jewish holidays?” I ask.

“I think so,” he says. “I went to Hebrew school four hours a week up through my bar mitzvah. I hated it, of course.”

Did he tell his parents he wanted to stop? “No. I didn't think it was an option. It was part of the program. But I'm happy for the experience now and if I'm lucky enough to have children someday, I'll do the same thing for themâto give them a sense of purpose and place. Part of who I am is based on the fact that we're taught that we have to fight a little harder, we're constantly challenged; as a people we're told âno' all the time. And you have to just believe in yourself, no matter what's thrown at you.”

David Copperfieldâborn David Seth Kotkinâremembers that his bar mitzvah made him sick with anxiety the night before. “I was sweating with a 102-degree temperature,” he recalls. “Midnight turned into 3 A.M., then 4 A.M. I had ice cubes on my head because I was so nervous about remembering my haftarah. At the time you had to learn it from a record, there were no cassette tapes; so the cantor would actually cut an LP for you. I took that LP to my non-Jewish summer camp and learned my haftarah by LP. There were no headsets. I was playing it in my room the way they broadcast reveille.”

Copperfield, forty-nine, dropped all Jewish observance after his bar mitzvah. “Even though my mother was born in Israelâshe moved here when she was five years oldâthere was no motivation to continue it. There was nobody pushing me along to do it. The focus changed.” He says he's not the type who sticks with things. “I lasted in college for three weeks; I went to Fordham University, which is a nice Jewish school; I'm jokingâit's a kind of Jesuit school. I dropped out after three weeks, and twenty years later they gave me an honorary doctorate. So my Jewish mother got to see me become a doctorâeven though it was the honorary kind.”

I tell him I read an interview he gave the

Cleveland Jewish News

in which he related doing magic to being Jewish. “What did I say in the article?” he asks me. I read him his quote: “

We are taught throughout childhood

not to take âno' for an answer; it is possible to turn âno' into âyes' and that is what

magic is all about

.”

Copperfield looks at me. “It's my quote, so you can use it again,” he says with a smile. He grabs my list of prepared questions out of my hands. “I'll say it again right here.” He starts to reread his own quote aloud. I ask him if he could elaborate instead. “I think every human being to a certain degree is persecuted,” he says. “We're taught in the Jewish culture the same story over and over again, whether it's in

Fiddler on the Roof

, the Holocaust, or the Maccabees: that we have to rise above persecution and do our best. Magic is about making people dream and taking impossible things and making them happen; taking things that aren't supposed to be and turning them into something beautiful. Houdini was a Jew; I'm a Jew.”

I ask if he's ever thought about the nexus of being famous and Jewish. “For me, I'm a little fearful sometimes if I'm in various countries that there will be a crazy person that will be a Jew-hater and want to make a point. And I'm not trying to make any political stands. I'm just trying to help people dream and grow. So that crosses my mind. My parents are always a little bit nervous because I have shows everywhere in the world and I'm pretty popular in a lot of countries that are anti-Jew.” Which countries? “I don't really want to talk about that,” he says.

“So I don't deny being Jewish,” he continues. “But I don't really push it. Not because I don't believe in who I am, I just think there are people out there who will make up their own scenario in their heads, especially now.”

He also thinks that highlighting one's religion distracts from one's work. “If Danny Thomas was known as a Lebanese guy, I think we'd be focusing on that,” Copperfield says. “Casey Casem: Arab guy. But it should be about his Top 40 Countdown. Winona Ryder: I think it's pretty cool that she's Jewish: hot-looking girl, really talented. I don't think it's a matter of hiding it; but not emphasizing it just allows people to focus on their work. I'm trying to thinkâthe people who are non-Jews that are famous, do we talk about their religions? Do we know what Halle Berry is?”

I ask if he would be uncomfortable being known as a Jewish star? “My answer would depend on the political climate, just for the safety of my family. I can do more good as a person that is apolitical and I can make more people happy and have people escape more than as a person that is becoming symbolic.”

He says he's very comfortable performing in Germany, where he has broken records for sold-out crowds. “I was engaged to a German girl for six years,” he adds, referring to supermodel Claudia Schiffer, with whom he broke up in 1999 after a much-publicized romance. “In Germany, they make such a big deal of the Holocaust and teaching the Never-Again mentalityâthey drill it into people's heads. So they overcompensate.”

I speculate that planning a life with a German woman could have raised issues for someone Jewish. “It didn't,” he says quickly. “It matters in one sense: I hope that when I settle down with somebody whom I can trust and trusts me, that our children can be brought up Jewish and go through the same torture I had when I was a kid. Because I think it did do me good at the end of the day. I've had a few long-term relationshipsâsome famous, some non-famous, and most people have been agreeable to that idea.”

His assistant lets him know that his fried chicken has arrived. I ask, finally, why he changed his name to Copperfield when he was starting his career. “I don't know,” he says absently. “I didn't think Kotkin was a catchy enough name.”

So it wasn't that Kotkin sounded too Jewish?

“Do you think it sounds Jewish?” he asks. “I don't.”