Stars of David (44 page)

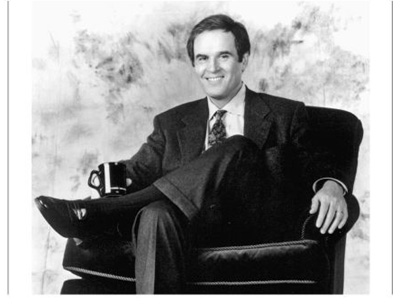

Charles Grodin

“I WAS ACTUALLY THROWN OUT of Hebrew school,” says Charles Grodin, the actor/writer/director/talk-show host who asks me to meet him in an empty Broadway theater before a rehearsal. “It's because I asked questions if I didn't understand what was going on. It wasn't the only place I was thrown out of around that age, and always for the same reason. I think I always asked questions politely, but my persistence alienated people. Still does.” Grodin, who grew up in Chicago in an Orthodox family (his grandfather was a rabbi and Talmudic scholar), speaks in run-on sentences. (“I'm the kind of interview,” Grodin confesses, “where you just say, âHello,' and I'll answer you for an hour.”)

“I changed Hebrew schools and there was a fellow named Rabbi Morris Kaplan who was the father of my closest friend and he became the head of the League of Rabbis in Los Angeles and he was a spellbinding story-teller and he would tell all the stories from the Old Testament and he wrote my bar mitzvah speech and, because a lot of my family was from Chicago, it was a triple bar mitzvah in Chicago and because he wrote a very good speech and I delivered it adequately and it was the date of the birth of Israel, it got applause, which is inappropriate in a synagogue, but I think that's where I first got the idea to go into show business; I said âOh, that's a heck of a feeling right there.' And that was it.”

Grodin believes he got more than a taste for theater out of Hebrew school. “I think my whole value system came from Hebrew school,” he muses. “That you're supposed to be honest, to look out for other people, not to sit around and bad-mouth people or find things wrong with people, and that's what I've really carried forward. It was all part of what I absorbed in Hebrew school and what I observed in my house.”

He left homeâand Jewish observanceâwhen he was eighteen, and gives his own kids more culture than ritual. “I'm now doing it with my son who's fifteen. Today I made him a Nova Scotia salmon bagelâcream cheese, onion, tomatoâand he said afterwards, âBoy, you really know what you're doing.' Now I'm going to have to see how tough he is: I'm going to do herring and sour cream with him and see if he can handle it.”

His current wifeâhis secondâjoined a temple in their Connecticut neighborhood. “I don't go to the synagogue,” he says, “but I was talking to my wife yesterday, and told her that my two main goals right now are to figure out what I can do to make some kind of a contribution to the well-being of other people, and to also try to somehow connect with nature. I know that sounds pretentiousâbut I've never been good at stopping and looking at anything. Those are the two things that provoke me and IâI don't know, does that have to do with Judaism? I don't really know, it's just a way of being. You know, I read in one of the weekly magazines yesterday that Nelson Mandela was equating Israel with Iraq, since they both have nuclear weapons, or they might. I think the more anti-Semitic talk or the more anti-Jewish feeling I hear, the more Jewish I get.”

Grodin himself has never felt any anti-Semitism. “No one thinks I'm Jewish; I don't look it. And I haven't heard much prejudice around me, although I do get the sense sometimes with some people that there's just an underlying assumption that the Jewish person is going to do you in. I feel the opposite: that it's much more likely you're going to get help from Jewish people, that Jewish people are going to be more sensitive. So I don't really get it.”

Grodin did get a taste of Jewish sensitivity when there was a Jewish outcry over the film

The Heartbreak Kid

(1972), in which he played a Jewish man so obsessed with a shiksa girlâplayed by Cybill Shepherdâthat he abandons his wife on their honeymoon. “I was the only person who seemed to see that the film would be taken as anti-Semitic,” Grodin says. “I definitely saw it that way. Initially I was just so excited to be playing a lead in a movie. But I was the only one that said, âYou know, they're going to hate this guy.' Everybody else thought I was just being self-protective. The first review I saw of that movie had a headline that said âYou'll hate him, love the movie.' But it bothered me, and I was living in an Upper West Side building at the time with a lot of Jewish people who commented that the movie was anti-Semitic because of my behavior of leaving a Jewish wife on a honeymoon for a gentile girl. When I was doing the role, I never thought of âJewish' and âgentile,' I thought of a girl who was driving me crazy and who looked like, you know, happiness is just around the corner. But there was ultimately resentment from Jewish audiences.”

Mirroring the film, Grodin's first wife was not Jewish, which he said disappointed his parents, Ted and Lena. “It was disturbing to my mother and to my first wife's mother as well,” he says. How did he navigate that? “I just went ahead and got married anyway,” he replies. “You know, a rabbi once told me that the children of mixed marriages are the biggest anti-Semites, which turned out not to be true at all.”

Grodin says he didn't care a wit who his grown children married. “I think it's so daunting to find somebody you could be married to. If that person turns out to be an Indian or a black person or something other than Jewish, so be it. My daughter is married to a non-Jewish fellow, and I pushed for the marriage. I just thought he was remarkable, and he is.”

Are Grodin's close friends Jewish? “Well, let me see . . . I've actually got a top-ten male friend list that I talk about for numerous reasons and let me just examine it; I never thought of it that way.” He runs them through in his head. “Number one is not Jewish, two is, three is, four not, five not, six not; I'd say it's about a split fifty-fifty.” So he doesn't find his Jewish pals inherently more compatible? “I'm friends with Phil Donahue, I'm friends with Regis Philbin, I'm extremely compatible with them.”

Grodin donates time to causes both Jewish and otherwise, but his Jewish loyalties, he says, get seniority. “I definitely lean in that direction. If there were two functions, I'd go to the Jewish one.” And though he's not an intense Jew, he'll occasionally draw the line at ecumenism. “I'm emceeing an event that the Kiwanis is giving in Connecticut for Christmas and now they're telling me, âWe're going to begin by all of us singing Christmas carols,' and I didn't say anything at the time, but I probably won't sing them.”

He says his consciousness of the Holocaust never leaves him, in part because his family lost relatives. “Just coming from Brest-Litovsk, which, depending on the year, was either in Russia or Poland around that time, there's no question: I have a powerful connection to that event. Oddly enough, any time I went to Barney Greengrass [the bagel and lox fixture on Amsterdam Avenue] when I used to live in Manhattan, or sometimes when I go into this beautiful Jewish deli where I live now, I don't know why, but at that moment I think of people in the camps and say to myself, âOh my God;

look at all this

.'”

Kitty Carlisle Hart

KITTY CARLISLE HART PHOTOGRAPHED IN 1977 BY JILL KREMENTZ

KITTY CARLISLE HART, doyenne of New York's theater society but perhaps best known for her fifteen years as a panelist on the TV show

To

Tell the Truth

, is dressed formally for Easter lunch when I meet her on a Sunday morning. The ninety-five-year-old answers her apartment door in a bright lime green suit, low black heels, a double strand of pearls, pink lipstick, and fingernails to match. With her proper appearance, patrician accent, and fancy name, Hart is not exactly the Jewish archetype.

“They changed my name when I went on the stage,” warbles Hartâ formerly Katherine Connâsitting primly on her velvet couch, a small black purse at her side as if she's waiting for a bus. “I found the name in the phone book. I originally wanted âVia Delia,' but I was persuaded against it.”

For all of her personal accomplishments as a singer and actress, Hart derived much of her early stature from her marriage to Broadway legend Moss Hart, director of

My Fair Lady

and

Camelot

, and coauthorâwith George S. Kaufmanâof The Man Who Came to Dinner and You Can't Take

It with You

. She was acting with the Marx Brothers in their 1935 classic film,

A Night at the Opera

, when she met her future husband for the first time. He was looking for a leading lady for his musical

Jubilee

, written by Cole Porter. “I didn't get the part”âshe smilesâ“but I got the man.” Not easily, she adds. “It took me nine years!” She almost giggles. I kept thinking, “âHe'd be so perfect! He's Jewish, I'm Jewish, I've seen all of his plays, I think they're wonderful, he's never been married, neither have I. Why doesn't he think of marrying me?'”

They were wed in 1946 by a justice of the peace in a small ceremony. “Moss said if we had a big wedding, we'd have to invite a thousand people,” she recalls. She says he knew as little about being Jewish as she did. “He cared about it politically,” she says. “He cared about it in terms of a consciousness of injustice.”

They celebrated no Jewish holidays, except of course when they were invited to Passover at the home of a prominent fellow thespian. “I once went to George Gershwin's forâwhat was it called where they read and put the matzos out?” she asks. “A seder,” I offer. “Yes,” she says with a nod. “Gershwin and Oscar Levant [the composer and actor] decided to do the whole seder in music. It was so wonderful! They sang and did the whole thing in jazz.” Who else was there? “I remember Robert Sherwood,” she muses, mentioning the playwright, “but I don't remember anybody else.”

Hart was definitely aware of her religion being heavily represented in her profession. “Everybody in the theater was Jewish except Cole Porter,” she declares.

Looking back, does she make anything of that or feel it was pure coincidence? “I think there are times when a whole flowering of some kind of an art form occurs. It happened in Greece when they built the Parthenon; they never did anything great after that. It happened with the flowering of opera in Italy. Jews had the American musical theater. And people don't know how to do it anymore.”

Hart was raised by a socially ambitious mother, Hortense Holzman Conn, who was cold and unaffectionate. In Hart's 1989 autobiography,

Kitty

, she writes:

“the moments of physical closeness were so rare that when I was

fifty years old, I was still trying to crawl into her lap.”

(Hart's father, Joseph, a gynecologist, died suddenly in the 1938 influenza epidemic.)

Hortense was determined to obscure their Jewishness. She sent her daughter to Miss McGehee's finishing school. “It's the chicest school in New Orleans,” she says. “Very grand; they call me an â

alumna

.'” She was conscious, as a child, of being different. “I felt peculiar at Miss McGehee's,” she says. Her classmates knew she was the only Jew. “They didn't want to eat lunch with me. They said it was because my mother sent my lunch with French bread.”

Hart says her mother wanted desperately to gain entrée into gentile society, and when they moved to Europe, Hortense managed to figure out how. “It was through music and bridge,” she explains. “Bridge in those days was âOpen Sesame' to society.”

And did Hortense successfully penetrate the upper crust? “Oh yes,” Hart assures me, her hands folded in her lap. “I came out in Rome

and

in Paris.”

But the party was short-lived. “We âpassed' as gentiles for years because it was easier to get up in society,” Hart says. “But then we lost what little money we had in 1929 and we came back to America. I had to get a job to support my mother. That was the best thing that ever happened to me; I was nineteen or twenty years old. I got a job in the Floradora SextetâI was going to singâ” Hart sings in a fragile voice that trills with age:

“Oh,

tell me pretty ladies, are there any more of them like you?”

During the Second World War, she entertained the troops around the countryâ“I always sang âThe Star-Spangled Banner'”âand she only gradually became aware of the hatred against Jewish people. “I went to a dinner party,” she begins. “In those days, everybody dressed up for dinner parties. And they were talking about the Jews in a way that was just awful. It was unbearable. And I got up in the middle of dinner and I said, âI am Jewish, and I won't sit here and listen to this kind of talk for another five minutes.' And I left. The bravest thing I ever did.”

Her stories are told in patchworkâwith loose threads of Jewish identity dangling here and there. Another snippet: “I once got into a taxi in New York with my mother”âshe's laughing at the memory alreadyâ“and after she dropped me off, the driver turned around and said to my mother, âThat's Kitty Carlisle, right?' And my mother said, âYes.' And he said, âIs she Jewish?' and my mother said, âShe may be, but I'm not.'” She laughs again.

One of the few times she went to synagogue was when her mother died. “My children were very small, and I wanted to give them a sense of finality. I didn't want to have this poor lady just disappear out of their lives. So I decided to take them to Temple Emanu-El on a Friday for the service for the dead. And I said to my son, Chris, âThis is the home of your forefathers.' And he looked up at the rabbis and said, âI only see three of them.'”

Despite the fact that she raised her children with Christmas and without Hebrew school, she seems to have silently preferred that they marry Jews. “Catherine is married to an Episcopalian, and my son, Christopher, is married to a Catholic,” she says. I ask if she ever cared that they marry Jewsâor told them she cared? “No,” she answers quickly. So she didn't care? Hart pauses. “I'm not prepared to say,” she says.

Hart's Jewish identity is obviously hard to pinpoint, but the strongest signpost of her connection comes in her sense of perilâa suspicion that Jews could be targeted again. “I always felt that the time would come when we would have our packs on our backs and be pushed out. I said to Moss one day, âDarling, where will we go when we get pushed out of this country? I have my pack on my back; are you ready?' He said, âWell, let me think about it. I tell you what: We'll go to the Gobi Desert. They have the best music, they have the best philosophers. Then again, who will fix the toilets?' That made me laugh so hard, I forgot about my fears.”