Stars of David (42 page)

She tells me that her opinion on Israel led to one of her few political disagreements with my mother during their long friendship. “I once totally dismayed your mom,” she says with a smile. “She will tell you about itâ ask her; I think she wondered at the time if she could ever forgive me. But I really felt somehow that Israel was kind of the last punishment of Hitler. To have created a necessity so tragic, that everyone became a nationalist. At the same time I was inspired by the kibbutz and the transformation of the military to include women; I found that very inspiring.”

Was there any point in her life when she wished she'd been more Jewish? “I wish I'd had the feminist seder all my life. But I don't wish I had what comes to mind in a more traditional sense when you say âJewish' because I think I had enough trouble trying to get over Marx and Freud.”

Interestingly, at least half of her closest friends are Jewishâ“which is disproportionate,” she acknowledgesâand she feels more simpatico with Jews. “Because there's a warmth and a vitality,” she says, “and because the Jewish tradition encourages your mind to work, includes social justice, is more circular and less hierarchical.” Not that she responds to every Jew who comes along. “I'm not convinced that every Jewish person in our crowd in New York has more warmth than every non-Jewish person: You know, some of them are pretty Episcopalian.” She laughs.

I ask if Jewish groups have pressured her to wear the mantle more publicly. “Actually the people who have pressured me to be a Jewish symbol, you might say, are the right wing. Because they're the ones who put out all the literature saying how feminism is a Jewish plot to destroy the Christian family. And they name us allâthe Jewish feminists.” She says her favorite specimen of hate mail, which she kept for years, was a postcard filled to its edges with vitriolic name-calling. “It was great because it had managed to get everything on one little postcard. It said something like, âNow that I've heard you speak, I know for sure you are a long-haired, Commie, dyke, lesbian slut who dates Negroes.' And then in the last line, it said, âIsn't that just like a Jew?'” She laughs. “It's really fantasticâthey got it

all

in there.”

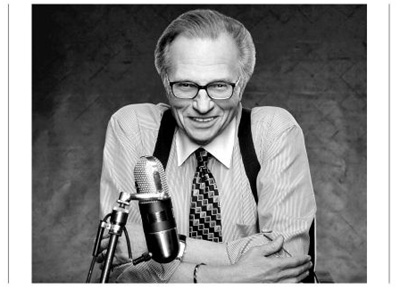

Larry King

“I ALWAYS LIKED SHIKSAS.” CNN anchor Larry King is being driven in a Town Car from the Regency Hotel, where he slept the previous night, across town to CNN's Manhattan studio. Tall and reed thin, he's wearing Façonnable jeans, black Nike sneakers, and his trademark suspenders. “I only loved three women in my life and none of them were Jewish,” says King, who has been married seven timesâtwice to the same womanâand is now married to Shawn Southwick-King. “When I grew up, nobody lived together; you just got married. So I got married. But in retrospect, I only loved three women in my life: I mean, in the sense where they could emotionally affect me.”

Does he make anything of the fact that the three wives he genuinely loved were gentile? “Never think about it,” he says with a shake of his head. “I didn't have anything against Jewish women. When I meet someone, I don't ask, âWhat are you?' I'm simpatico with a lot of people. There are a lot of links between Catholics and Jews.”

Did his mother care if he married a Jew? “She would have liked it if I did. But no pressure. I never saw her show an act of prejudice. For example, one of my cousins, Karen, got involved with a black guy. Her parents disowned herâher Jewish parents wouldn't talk to her. My mother? They came to her house for dinner.”

King's current wife is a devout Mormon. “She believes she's going somewhere after she dies,” he says. “I hope she's right.” But he points out that religious leaders who purport to believe in an afterlife aren't so different from those who say they hear voices from the grave. “Sometimes we have guys on our show who communicate with the dead,” King says. “They claim the dead come back and talk to you. And every time I talk to mainstream religious leaders, they say, âAy, those people are crazy.' I think, âWhat do you mean, crazy? They're saying exactly what

you

say!'”

King was turned off to Judaism back in Hebrew school in Bensonhurst. “I didn't like the God of the Old Testament,” he says. “The God that's printed there was vindictive, vain, petty, violent. Why would I want to share an afterlife with that God? And I never bought the whole storyâthat Moses went up the mountain and God spoke to him. I thought Moses was kind of a genius for coming up with Ten Commandmentsâmost of which don't make any sense today. For instance: âYou can't covet.'

Everybody

covets! You don't

do

anything about it, but who doesn't covet?

“So I'm not a religious JewâI grew up away from that. But I'm so culturally Jewish. For example, the

thought

of mixing milk and meat would cause me to throw up. I would

never

take a piece of steak with a glass of milk; I think I'd faint. I'll eat a piece of bacon. But it has to be very dry. And my mother used to bring home bacon that wasn't from a pig.”

His mother wasn't Orthodox, but she kept a kosher home, lit candles every Friday night, and hosted a seder. “And we ate Chinese food on Sunday like every good Jew.” King smiles. “I still do

yizkor

[tribute to the dead] every Yom Kippur even though I don't believe my mother is hearing it anywhere. I don't know if there's a God. I'm a classic agonstic, but I'm a Jewish agnostic. That is, âMaybe there's

something

! Don't count it out!'”

He no longer fasts on Yom Kippur. “I used to. Once I made a terrible mistake. I was a big smoker before I had a heart attack, and one year I broke the fast with a cigarette. This is not smart. When you inhale it, and you haven't had anythingâno food for twenty-four hoursâI thought I was going to topple over. I used to go to William Safire's house [the

New York

Times

columnist]; he used to do a big break-fast dinner. He'd say, âEat light. A little matzo ball soup first.'”

I ask about King's two young children (by his current wife), ages four and three at the time of our meeting. “They're going to be Mormons,” he says, “because my wife is so devout. When we got married, I said, âLook, since I'm agnostic, I have no right to tell you not to teach them what you believe. But give them an opening.' So if they ever ask me, I'd tell them the exact same thing I'm telling you: âI don't buy that God, I don't know if there's an afterlife.' I'll tell them the truth. I'll take them with me when I go to synagogue on Yom Kippur and explain what it is. I hope they choose what they want. Most people believe what their parents believe. You're a Mormon because your father was a Mormon. I'm a Jew because my father was a Jew.”

Would it matter if his children ultimately don't call themselves Jews? “It wouldn't be the end of the world if they don't, but I'd like them to know that they're Jewish,” he replies. “Whenever we apply to schools we list them as both Jewish and Mormon. I have three grown children tooâ a boy, forty-seven, another boy forty, and a daughter thirty-five. The only one of the five who goes to synagogue is the boy who is forty. He's raising his kids Jewish. I have five grandchildren. Three are being raised Jewish.” King pauses for a moment. “I just want my kids to be smart enough to learn for themselves and not be something by rote. I don't want to believe something just because my father believed it.”

His father, a Russian immigrant who spoke fluent Yiddish, died when King was very young. “He died on the way to work of a sudden heart attack. My mother never remarried and raised the two of us: I was nine and a half, my brother was six. Before I was born, she had lost a son named Irwin who died of a burst appendix when he was six. My father was buried next to him in Beth David in Elmont, Long Island, near Belmont racetrack. A very appropriate place for my father to be buried because he used to bet the races.

“I took my dad's death badly. I took it as him leaving me. He was very close to me. I didn't go to his funeral. In retrospect I was very angry. People said all the wrong things to me: âYou're the man of the house now; you gotta take care of your mother.' I got angry at my father: Not only did he leave me, but he gave me responsibilities. But I said kaddish every morning and every night. I'd go to synagogue in snowstorms. I'd always walk in, and all the men would feel sorry for me because most of them were in their forties and fifties and here was this little nine-and-a-half-year-old boy.”

King did manage to talk about his father in his bar mitzvah speech. He says the ceremony was bare bones because his mother was destitute. “We were just getting off being on relief. We didn't have a party. I had the ceremony and then afterwards we served snacks in the anteroom.” He remembers studying for his haftarahâthe Prophets reading that follows the Torah portion. “The rabbi had his long beard and he used to put his hands through it. When I did my haftarah all in Hebrew, he stood right next to me and it was his fingers that went down the lines as I read. I had a long haftarah. When we were just beginning to study for our bar mitzvahs, my friends and I would always look up our haftarahsââHow long's your haftarah?'âbecause your haftarah depends on your birthday. And I had two and half pages. Sam Finkelstein had half a page. What a break.”

King once said that growing up in Brooklyn, he didn't know what a Protestant looked like. “Ninety percent of my friends were Jewish. We had a club called the Warriors. Occasionally the Italians would yell at us, âYou killed Our Lord!' So one day my friend Herbie confessed. He said, âOkay, we killed your Lord, but the statute of limitations is up.'” King laughs.

“Since I was a kid, I never understood prejudice. I always regarded it as stupid. It means to prejudge. I don't do it when I interview. I don't expect someone to be good or bad. To judge a people by what their religion or color happens to be is self-defeating. When I came to Miami the first time, I got off the train with sixteen dollars in my pocket to try to break into radio and the first thing I saw were two water fountains: one said âColored,' one said âWhite.' I drank out of the âColored.' I sat in the back of the bus where blacks were supposed to sit. I've never had a rational explanation for bigotry. Hitler took away the best of his community: The Jews of Berlin were the symphonic maestros, the medical leaders. He chased Einstein out! It makes no sense to me.

“Lenny Bruce used to say, âThere will always be prejudice, because people need people to kick around.' He was a great friend of mine. He said this in 1960: âSomeday blacks will get equal rights, and when they do, we're going to have to find someone else to pick on.' He says, âI got it! Eskimos! We'll pick on Eskimos! Did you ever meet a bright Eskimo? Would you ever be taught by an Eskimo leader? Can you name a famous Eskimo author? No! Eskimos cause problems.'”

Larry King changed his name from Lawrence Harvey Zeiger early in his radio career in Miami. “Nowadays, they wouldn't have changed it,” he says. “Today in broadcasting, any name goes. But when I started in 1957, right before I went on the air, the general manager asked me what name I was going to use. I hadn't even thought of it. He had the

Miami Herald

newspaper open to an ad: âThe King's Wholesale Liquors.' So he said, âHow about Larry King?' And I said, âFine.'”

When people argue about anti-Semitism or anti-Israel sentiment on his program, King says he tries to stay out of the fray. “When I'm doing my show, I'm a journalist. Do I want the Jews to survive? Of course. Do I hope there's peace in Israel? Naturally. I'm emotionally a Jew. It's like Irish New Yorkers who rooted for the IRA: I have an understanding of them.”

He defends the instinctive loyalty toward one's own. “When people ask, “Why do blacks root for black athletes?”âI know the answer. I root for Jewish athletes. Why? You just want to see them do better. Any minority roots for the minority to do well. Why is that strange? If I go to the voting booth and I'm voting for the state legislature and Goldstein is running against Smith, I vote for Goldstein.”

After a bout with midtown traffic, we've arrived at the CNN studios on Seventh Avenue near Penn Station. We conclude the interview in the elevator: What would he consider the most Jewish moment in his life? “Being recognized on the streets in Israel,” he says. “Standing at the Wailing Wall and having a rabbi say to me, âSo what's with Perot?'

“I think also one of the most unique moments was when I addressed the graduating class of Columbia University Medical School. I stood up in the Columbia robesâI never went to collegeâand I said that I had this vision of my mother looking down, rubbing her eyes, looking again, and saying, âHe's a

doctor!

'”