Stars of David (22 page)

Talking about Wieseltier's parenting, I wonder about his father; it struck me, as I finished

Kaddish,

that I had little grasp of who his father was. “That's right,” he says with a nod. “I wasn't writing a memoir. And it's none of my reader's business who my father was.” But wasn't it part of the process of saying kaddishâto reflect on his father and their relationship? “It was to a certain extent, but that's not something that would be of interest to other people as far as I'm concerned. That strikes me as a private matter. And again, one of the reasons I wanted my readers to know almost nothing about my father is that I did not want my religious life to be reduced to my filial life. That's why I did no promotion for the book. No book tour, no radio, no author's photograph, no blurbs; nothing,

nada

,

niente

. My publishers thought I was mad. But I said to them that I did not want to travel the land being asked psychological or soap-operatic questions about a father and a son. I was writing about religion and philosophy and life and death, not about Mark Wieseltier and Leon Wieseltier. There had to be enough about me as a son to make it clear that all these texts of mourning were being lived and not just studied. But not so much that the study of mourning in Judaism could be reduced to this son's experience of it. It was tricky.”

If he doesn't want to tell me about his father, can he at least tell me whether the year spent saying kaddish for him was a kind of reckoning? “Of course it was. And the reckoning I made with him turned out to be unexpectedly free and candid precisely because I was doing my duty. I squandered no energy on guilt or delinquence. I simply made myself into an instrument of my obligations and proceeded to think my thoughts. My thoughts about my tradition I recorded; my thoughts about my father I did not.”

Does he concede that those few times in the book where he describes his father as difficult do beg the question of what this man was to him? “Sure, but discretion is a large part of dignity. It is perfectly clear in my book that the author loved his father and was wounded by the death of his father. Also that he was a Polish Jew who came to the States after the war, the sort now known as a Holocaust survivor, and a troublesome man. That seemed enough.”

I ask him to flesh out the story he tells in the book about the time a friend of the family offered to say kaddish for his father in his place. “I just went to that man's funeral,” Wieseltier says with a dose of irony. Why did this man make that offer to be his surrogate? “Because he didn't trust me,” Wieseltier answers. “Because I was heterodox in many ways and the family knew it. And you know, the kaddish, like a lot of contemporary Orthodoxy, has been absorbed into a folk-religious view of things, and so basically he was worried about the fate of my father's soul and so the kaddish, three times a day, was absolutely essential to get my father a good verdict.”

In the book, Wieseltier is less sanguine about the incident:

“I was furious,”

he writes.

“I do not deny that I live undevoutly, or that the fulfillment of

this obligation will be arduous for me. But it is my obligation. Only I can fulfill it.”

This responsibility clearly brought him back to the fold, so to speak.

“I

was a pariah until I became a mourner,”

he writes.

“Then I was faced with a duty

that I refused to shirk, and I was brought near.”

I remind him of another passage:

“All my life I went to shul with my father,

that is, I went to shul as a son. It was because I found it almost impossible to stop

going to shul as a son that I stopped going to shul. I came to conflate religion with

childhood. But childhood is over.”

It's the notion we discussed earlier, of leaving the childhood “trauma” of Jewish indoctrination behind and reclaiming it. “I wanted to be a Jew on my own,” Wieseltier emphasizes. “I didn't want to be just an heir. I knew that I was an heir and in my ways I lived all my life as an heir; but I wanted to be an autonomous individual as a Jew also. And then I could consent again to being an heir. If you're just an heir, then you're still a child, merely a son, forever a passive receptacle. I wanted to be an active receptacle. And so I had to break out of the tyranny of the family over my spiritual and intellectual life. And out of the tyranny of the people and its politics, too. On some level I keep my Jewishness private from other Jews as well; I don't want them to ruin it either.”

I personally relate to this idea of one's religion being tied up inâand muddied byâfamily expectations or obligations. I read Wieseltier his line,

“Religion is not the work of guilty or sentimental children.”

He nods. “Look, in the matter of religion Freud was philosophically wrong and empirically right. He was philosophically wrong that religion is simply an expression of reverence for the father. It is notâwhich is one of the reasons I've never liked the concept of God the Father, the way I don't like God the King. One has to be very careful about the metaphors that one imports into one's beliefs about the world. But he was empirically right in that for most people religion is simply an enlargement of their attitude towards their parents. And that's a terrible thing. It means in the matter of religion most people are permanently children. And so religious life to them becomes a process of endless re-infantilization. Over and over again. It's insulting to the soul.

“Religion is about the fate of every individual soul. Religion is not even primarily a collective thing. The practices, the rituals, the gatheringâ that's for the people, that's for the family. But family life is not the same thing as spiritual life. (And often it's the polar opposite.)”

I tell him that, for many of the people I've interviewedânot to mention many people close to meâreligion

is

primarily about family. “That's because people cannot disassociate their religious life from their parents because they think that being religious is a way of being good little boys and girls. And of compensating for the distance that they've traveled from their origins, of making up for all the other ways in their life where they refuse to be good little boys and girls. It's the peace offering that they bring to their living or dead ancestors. And they are encouraged in this reduced sense of religion by many Jewish institutions, which give the impression that all that matters to Judaism is the children. But Judaism is not for children. I mean, there are children who have to be raised as Jews, but this is not essentially about the children. This is about the spiritual existence of mature souls and moral agents.”

Wieseltier gets a phone call from his wife: She wants to know if he's ready for her to swing by and pick him up at the office. Before he goes, I want to know what Wieseltier would advise someone if they came to him asking what it means today to be Jewish. “The one-word answer is âJudaism,'” he says. “That's the only answer there is or ever will be. Everything else is a corollary of that. I mean, the Jews are a people, the Jews are a nation, the Jews are a civilizationâbut they're all of that because they are first and foremost a religion. That's the source of the whole blessed thing. Except for our religion, we would not be a people. When Jews come to me with perplexities about the meaning of Jewishness, I say to them: Judaism. Just go to it; check it out, study this, study that, try this, try that, humble yourself for a while before it, insist upon the importance of having a worldview, develop reasons for what you like and what you don't like,

get

into the fight

. Get into the fight. That's the one-word answer: Judaism.”

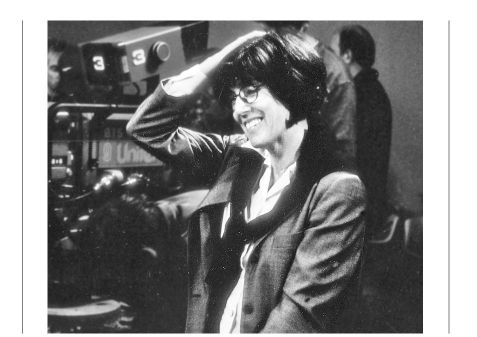

Nora Ephron

NORA EPHRON PHOTOGRAPHED BY BRIAN HAMILL

NORA EPHRON CAN'T DEFINE Jewish humor and doesn't seem interested in trying. “I don't know what that means,” she says over the din at an overpriced café on Madison Avenue. “I just know that there is a tradition of humor that I think ofâfor example, in what Woody Allen used to do in his stand-up comedy routine. He would get up and talk about all the women who rejected him, and by the time he was five minutes into it, every woman in the place wanted to go home with him. So I'm certainly very conscious that I think of stand-up comedy as being fundamentally Jewish. That kind of personal approachââIf I can make you laugh, you'll like me'âthat seems to me to be some sort of distant cousin to whatever one might think was a Jewish tradition or humor. But I don't think of myself as a Jewish humorist or a Jewish writer in any real way, even though in some way I think of myself as a Jew. Or as

Jewish

, but not a

Jew

; or as a

Jew

, but not

Jewish

.”

Ephron feels like she's been categorized as more Jewish than she actually is, because other people make an issue out of it, even if she doesn't. Raised without any Jewish education by atheist parents who had “contempt” for religionâ(“My mother believed that organized religion had in one way or another been responsible for almost everything bad that had ever happened”)âshe doesn't exactly exult in her Jewish identity. “At this point, it doesn't make the top five of what I would say about myself,” she says. “And it probably never did.”

Nevertheless, she believes it's an undeniable part of her makeupâa realization she made at Wellesley College, when she found herself gravitating toward other Jewish women. “It was clear to me that we were very interesting. There was nothing bland about us in a college filled with many bland young womenâmany of whom didn't know what they thought, what they believed politically. Whereas the Jewish girls were very opinionated and vital and fun and funny. It was sort of interesting to me to discover that I was drawn to this group. I definitely had a sense that there was some kind of . . .

thing

about Jewishness that was not what I had grown up withâwhich had been a delicatessen Jewish, a well-read-parents Jewish. It became clear to me that some of what

I

was was Jewish, in some way or other, even though it had nothing whatsoever to do with religion, which continued not to interest me at all.”

She was fascinated, however, by Wellesley's required Bible-reading course. “âBible' was fantastic. But I got the only D that I ever got in college when I wrote a paper saying that Jesus had never really meant to start anything new, he was just objecting to some of the things about Judaism. Which I still believe is true, by they way, but my bible teacher did not like my theory.”

In pearls and a black sweater, her brown hair neatly framing her face, Ephron speaks with her unmistakable drone: a combination of dry humor and imminent irritation. I ask her, for instance, if she still has a copy of the college paper about Jesus. “No, of course not,” she says dismissively.

“One of the questions you asked in your e-mail,” she moves on, referring to my interview request, “was whether it had ever been an advantage to be Jewish. It was definitely an advantage to be Jewish at Wellesley because there were so many Jewish guys at Harvard and Harvard Law School. And a lot of them were under strict orders to date Jewish girls. The Jewish girls at Wellesley and Radcliffe had, I think, a much more active social life than anyone.” Did she seek out a Jewish husband? “I don't think I necessarily wanted to find a Jewish guy, but I wanted to find a

funny

guy.”

It's unclear how funny her first two husbands were, but they did happen to share her background. “I did marry two Jewish guys. The first was Reconstructionist.” The second, well-known journalist Carl Bernstein, is the father of her two sons. Her current marriage to journalist Nick Pileggi (not Jewish) is seventeen years old.

Her boys grew up going to Passover seder at the home of Bernstein's parents. “Neither of my boys asked to be bar mitzvahed, which was a gigantic relief to me,” says Ephron. “First of all, because of my feelings about religion, and second of all because they're so expensive, and third of all, because nothing is more awful than a divorced bar mitzvah. But they didn't ask for it, despite the fact that they were in the height of the bar mitzvah madness; they both went to Dalton [a top private school in Manhattan] and attended bar mitzvahs that cost more than I made until I was about fiftysix years old.”

She doesn't care who her sons end up with, or how they choose to raise their children, if they have them. “I believe that it makes it hard on the marriage if someone is religious and the other one isn't. But that would be

their

problem, not mine. My husband is not Jewish and it's definitely my happiest marriage and sometimes I think that that's one of the reasons. Given that almost everyone I know was raised in some religion or other and they don't observe it in any way, it seems to me fairly idiotic to get worried about what one's grandchildren are subjected to.”

Her parentsâboth Hollywood writersâtold her as a child that they had no interest in religion, but that she was welcome to it. “They said to me that they were not sending me to Sunday school or anything because they didn't believe, but that, if I ever wanted to be any religion, it was fine with them. So when I was about twelve years old, I went to camp in the summer, and I was a voracious reader and I read

Charles and Mary Lamb's

Bible Tales

. And I came home from camp and said to my parents, âYou know you always said I could be any religion I wanted?' And they said, âYes?' And I said, âWell, I've decided I want to be a religion.' And they said, âWhat religion is that?' And I said, âPresbyterian.' And they said, âWhy?' And I said, âBecause I believe in Our Lord Jesus Christ.' And they bothâ I'm not kiddingâlaughed so hard, they fell on the floor. And that was the absolute end of my brush with Christianity. I cared way too much about their opinion to survive an episode like that.”

She recalls that her parents' Jewish friends were casually connected to their religion, “some of which was manifested by conversations about whether there were any Jews playing in the Rose Bowl,” she says deadpan, “and if there were, shouldn't we be backing that team as opposed to others?”

Her Beverly Hills neighborhood has changed demographically from her youth. “When we moved there, I was five and there were still Christians in the Beverly Hills school district; but by the time I graduated from college, you had to drive to the San Fernando Valley to see a house with Christmas decorations.” Unless of course you drove by the Ephrons' home. “We celebrated Christmas and it was

mild

compared to the way I celebrate it now,” she says. “I

love

Christmas. And you know, I always went to school on the Jewish holidays, because my mother said, âWhat are you going to do if you stay home?'”

But it was Wellesley, in 1958, where she had an epiphany: being Jewish marked her in some inevitable way. “That was the most interesting moment for me in terms of realizing this was something I'd better think about,” she says. “After I was admitted, they sent me a little housing form where I was supposed to put down my religious preference. It was the first time I was asked if I had a religious preference. I had, for example, not wanted to go to Mt. Holyoke because it had compulsory chapel. But anyway, I got this thing from Wellesley and I didn't know what to put: I didn't think that âatheist' was a religious preference. So I thought that leaving it blank was sort of the right response. And I got a letter back saying I wouldn't be given a room assignment till I told them my religious preference. So I wrote them a letter saying that I was an atheist but I had been born a Jew. And then I went off to Wellesley and it was absolutely clear to a

blind

person that Wellesley's housing department worked in the following way: Catholic girls roomed with Catholic girls, Jewish girls were put with Jewish girls, and Protestant girls were put with Protestant girls.

“When I was working on the school newspaper, we exposed this policy. And I went to interview the âdean of housing,' as she was called, and she justified it by saying [Ephron dons a perfect schoolmarm voice] âWell we wouldn't want a Christian Scientist to room with a doctor's daughter, would we now?' And I said, âWell, why not?' So the policy was ultimately changed. But at Wellesley I suddenly realized that whether I thought of myself as a Jew or not,

other

people thought of me as a Jew, and I had to come to terms with what that meant.

“And then my best friend my freshman year was from someplace like Cincinnati or someplace like that and she had never been friends with a Jew. She told me there was such a thing as âJewish legs,' but that I didn't have them.” What are Jewish legs? “Well, I can draw them for you,” Ephron says, though she doesn't. “I know what she meant,” Ephron says.

As soon as Ephron graduated, she went directly to New York City, instead of home to Beverly Hills. “You could substitute the word âJewish' for New York,” she states. “From the time we moved to California till the time I moved back to New York at twenty-one, I was truly in some horrible Diaspora. I couldn't believe we had moved to California when I was five; one of my earliest memories is thinking, âWhat am I doing here?' And couldn't wait to get back to the place where I felt like myself.”

Fans think of Ephron as a die-hard New York enthusiast; her filmsâ

When Harry Met Sally, You've Got Mail,

and

Sleepless in Seattle

, with its Empire State Building finaleâbear this out. But though many Jewish publications and even

Amazon.com

reviews have described Ephron as a Jewish humorist in the tradition of Woody Allen, she reiterates that she doesn't see herself as a Jewish writer. “It's like being interviewed as a âwoman writer,'” she says. “Obviously I'm a woman writer, obviously I'm Jewish. But it just seems like a narrow way of looking at what I do. When someone says, âOh, you're a woman writer' or âYou're a woman director,' then you kind of say, âReally? Is that what you think I am? Don't I make

movies

?'” But she's not so bothered that she calls people on it. “I'm not that interested in makingâas a Jew would sayâa megillah out of it.'”

Though Ephron doesn't write explicitly Jewish movies, I'm curious about whether she thinks an overtly Jewish story is marketable today. “I don't think there's any question but that if you write something that is Jewish, you're going to have trouble getting it made,” she says. “Because they're not going to go see it in Athens, Georgia. There's lots of stuff they aren't going to go see in Athens, Georgia, and that's one of the things they're not going to go see. By the way, they didn't go see

When Harry Met

Sally

either: I just remembered hearing what our grosses were in Athens, Georgia, that first weekend and it was the only place not doing any business. The point is that there are big-city movies, there are movies that play in L.A. and New York. If you're doing a movie about being Jewish, it's not going to be a big-city movie.”

She seems struck by the paradox that many Hollywood pioneers were Jews and yet explicitly Jewish movies don't usually get made. “Jews basically started the movie business, which is responsible for all the American dreamsâtheir immigrant dreamsâthe dream of the happy family and the perfect farm. But movies are a mass medium, and these days, when it costs sixty or seventy million dollars, you want it to be a movie that everybody is interested in.”