Stars of David (18 page)

“Melissa was going out with him [John Endicott] for seven years, so it's not like, when they decided to get married, I fell against the door and clutched my heart. Obviously this was what was coming down the pike. But it made me very sad. I always had the fantasy that he would see how great Judaism is, how logical and ethical it is, and he would end up saying, âThis is what I want.' But we never got to that.” Endicott and Melissa divorced five years after the weddingâan interfaith ceremony that still makes Rivers shudder. “We had a rabbi and a ministerâyou know, one of those terrible marriages. I mean, what's the baby going to be?”

Indeed: What is the baby? Edgar Cooper Endicott, according to his grandmother, is absorbing the traditions of the parent he's with most: mom. “He's with her now, and the mother's Jewish, and so it's whatever you come out of,” Rivers says. In other words, custody is destiny. Before the separation, Melissa did not welcome her mother's questions about how her grandchild would be raised. “It was always, âWe'll make the decision,'” Rivers recalls. “I pushed because I just didn't want him to be

nothing

. But then I thought to myself, âDon't worry: I'll get him in New York for Passover, Hanukkah, Yom Kippur. He'll know what he is.'”

Though Rivers clearly has a clannish instinct, she says she wasn't consciousâduring most of her careerâof who the other Jews were in show business. “But now, I

am

more aware and I've started to use it.” She explains that there was a “new regime” of executives at the E! Channel, where she was a host, and she couldn't break the ice with them. “I finally turned to one of them and began to talk about Sunday school. And we now talk to each other as Jews! I just got flowers from them with a note that said, âThe

mishpucheh

[family] loves you.' I said to Melissa, âI don't know if I'm shitting them or they're shitting me.' Cause we're all connecting on this big Jewish level now. But generally, I don't think that helps at all in the businessâthe way AA [Alcoholics Anonymous] members have each other or gays have each other. I don't think that's there for Jews. It's never been there for me.”

And despite the fact that she is in many ways the archetypal Jewish celebrity, she says that she's not the one Jews put up as the famous face of Judaism. “Oh, I only wish I were! Are you kidding? Oh, how wonderful to say, âShe's the one we look to.' I think they look to Barbara Walters, this age group. Which is stupid. Come over here! It's more fun over here!”

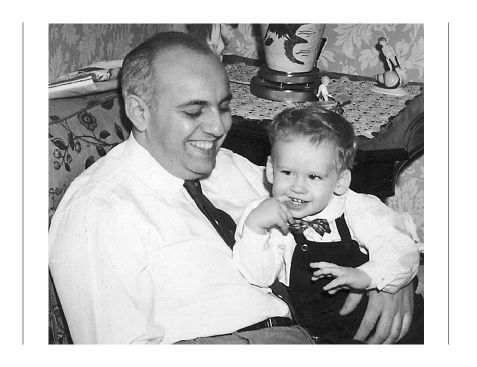

Jerome Groopman

JEROME GROOPMAN, M.D.âan expert in AIDS, cancer, and rare blood diseases who helped discover the drugs that made AIDS survivableâ is a hugger. “I was kissed from the time that I was a little boy,” says this broad-shouldered, six-foot-five-inch oncologist, pictured above in a tallis, who is folded into his office chair on a cold day in Boston. “It was natural for my uncles to kiss me, for neighborhood men, who were Eastern European Jews, to embrace me. It was a different sort of cultural expressionâ perfectly natural.” He says the affection he grew up with in his Bayside, Queens, neighborhood informs the way he administers to his patients. “I just can't imagine not touching someone,” he says. “It's sort of a recognition of another person's humanity.”

I tell him that when I read his book

The Measure of Our Days

, I noticed how many times he described hugging a patient or holding his or her hand. Groopman, fifty-five, with a bald pate, white beard, and wire-rimmed glasses, acknowledges that his physicality is connected to the affection he received from the Jewish community growing up. “Absolutely,” he says. “It's very strong.” He notes there was a reaction to his article in

The New

Yorker

magazineâwhere Groopman has been a staff writer since 1998â when he wrote about Christopher Reeve and his miraculous spinal cord regeneration. “Someone who knew Reeve quite well said to me, âYou touched him when you met him? No one touches him.' But how could I not?”

He refers to his professional ethos as “the medicine of friendship”âa phrase he first heard from a Protestant patient. “In Judaism, when you say a prayer for someone to get better, it says you should heal the spirit and heal the body. I thought to myself, âThese prayers are always constructed for a reason, in smart ways: So why does it say heal the spiritâthe soulâ

before

you heal the body?' It's too simple to say, âThat's because there's a mind/body connection,' because there are plenty of people who have positive thinking but die anyway. So this sort of glib

mishigas

where some guru says, âIf you just think right, your breast cancer will go away,' or Norman Cousins says, âLaugh and your lupus will go in remission,' just doesn't work. Ultimately for all of us there will come a time when asking for the body to be healed won't work: because we're mortal beings. But until the very last breath, you can always heal the spirit, reconcile yourself with people in your life, with yourself.

“And that's where the medicine of friendship comes in. I think embodied in the prayer for healing [

tefillat mi sheberach l'refuah

] is the imperative to the doctor that when he or she no longer has the drug to give or the surgery to perform, that they are still there. They're there to try to help that person arrive at a place where they can heal their spirit.” Groopman folds his hands around a lanky knee. “I think it's what

I

want in a doctor,” he continues. “I want someone to know who I am. I realized this while working in oncology and in AIDSâespecially before the drugs were developed. How much could I really give someone sometimes? But I was

there

. That's what you give them.”

Groopman has groupies; chiefly, it seems, because he flouts the paradigm of the dispassionate scientist. He writes about his cases often in spiritual, hopeful terms, always careful never to whitewash the callous realities of disease. But Groopman's fans, drawn to his humility and candor, don't necessarily know about the intensity of his religion. “There's no corner of my life where it doesn't somehow inform or influence me,” Groopman says. “I mean, I definitely grew up with an identity which was informed by strains of paranoia and distrust and fear about the gentile world. My grandmother had witnessed pogroms in Lithuania and my mother's extended family had been largely exterminated in the Holocaust. So this fear wasn't fantasy; it was the real thing. But I think the wonderful thing about Judaism is it makes you a fuller human being. I mean that's really what the Talmud isâthis undertaking to say, âLet's describe the whole human experience.' So there is no separation for me.”

He was tutored in Yiddish as a boy because it was the language of his relatives, chose to write his thesis for Columbia University (class of '72) on Marx's impact on the kibbutz movement, and spent a college summer studying at the Weizmann Institute in Israel. He keeps up with the weekly Torah portion (he once described Talmud as a “compendium of second opinions and opinions on opinion itself”), visits shul on Saturdays (at one point, he belonged to five temples), and davens with tefillin. “At times I wondered if I should become a rabbi,” Groopman says, “but I didn't think my faith was unalloyed. There were times of doubt or times when the ritual felt contrived. I certainly couldn't imagine dealing with a board of trustees at a shul,” he says with a laugh.

The Jewish pride with which he was raised was insisted upon by his father. “He had made a decision, which was communicated to me, that he would not try to pass or assimilate,” Groopman explains. “In terms of who we were and how we represented ourselves to the gentile world, there was no compromise. No name changing, no nose jobs; none of that.”

Groopman says he has tried to relate that same religious dignity to his own three children, albeit without heavy-handedness. “I'm not the kosher police,” he says. “Everyone has to be kosher in the house, and then they decide what they want to do when they're eighteen.” Similarly with ritual: “I want synagogue to be a positive experience,” he says. “I don't want it to be suffocating or rammed down their throats.”

When it comes to teaching his kids about Jewish values, Groopman says, “It involves tremendous respect for othersâremembering the idea of having been the persecuted minority. And because of the work I do with AIDS, my kids are very conscious of gay civil rights, very conscious of not being anti-Arab, anti-anything. There's even a rabbinic conceptâ

Kiddush

hashem

âwhich means that Jews should act in such a way that they reflect positively on Jewish values and on the community.”

Groopman's wife, Pamela Hartzbandâan endocrinologist who is also Jewishâdid not share his devout upbringing. “The woman I married grew up completely assimilated with almost no background in Judaism,” Groopman says. “I'd always thought I was going to marry the

rebbetzin

[rabbi's wife]. I didn't. I fell in love with someone who I would say embodies all of what is marvelous and important in the tradition. She had grown up in Londonâher father was a chemical engineer who worked for Esso. They didn't keep kosher, hardly did the holidays. They thought I was the Lubavitch rebbe when they first met me,” he says with a chuckle. I can't help but notice that he could easily pass for one.

I ask if he and Hartzband had to reconcile their Jewish ground rules before they were married. “Yeah, we did,” he replies. “We had a big negotiation. And the deal was that she would agree to keep a strictly kosher house if I learned to ski.” He smiles. “My answer to her was, âJews don't ski.'”

Groopman marvels even today at how two Jews could be so different. “Her family was everything we weren't,” he says. “They were cosmopolitan, living in Europe, integrated into the gentile worldâshe hadn't grown up in a ghetto like I did. And they were avid skiers.” Ultimately, however, they bridged the gap. “I learned to ski and we have a kosher home,” Groopman says, looking pleased.

One of his sons is an “Arabist” at Columbia who developed his interest, in part, because of his father's friendship with Jordanian King Hussein's nephew, Prince Talal. Groopman treated Talal for cancer and they stayed in touch. “We're extremely close,” Groopman says, gesturing to a photograph on his desk. “And that's his wife, who comes from a very prominent Lebanese family; my son stayed at the royal palace with them. They are direct descendants of Muhammadâthe Hashemites. No kidding around. It's not like when you find fifty Hasidic rabbis who tell you they're the direct descendants of King David, but it's bullshit. These guys are for real.”

In addition to family photos, Groopman has on his wall an enlarged rendering of his book jacket for

The Biology of Hope

, which he says asks “whether you should ever relinquish the right to hope, and if there is an authentic biology of hope.” The book is being considered for a television series, which will mark Groopman's second foray into pop culture: the 2000 ABC drama

Gideon's Crossing

was based on his first two books, with the main character modeled after Groopman himselfâthe humanistic doctor.

The creators decided to cast Andre Braugher, a formidable actor who is black, for the role. “I wasn't against it per se,” Groopman says now. “They wanted Andre Braugher because he was such a great actor, and the character was supposed to transcend the fact that he was black. They wanted the audience, ultimately, not to care. Whether that was accomplished or not, who knows?” I ask him whether he sensed any hesitation to center a series around an explicity spiritual Jewish character. “You don't have any control of these things,” he replies diplomatically. “I think it would have been interesting and maybe even sociologically challenging to try to have the spiritual overtones that my book,

Measure of Our Days

, has. So I think that part was missing.”

The “spiritual overtones” of Groopman's life are revealed just by visiting his modest office. “It's not subtle,” he says with a laugh, gesturing around him. The array of Judaica is mostly gifts, he explains, from appreciative patients. Groopman gives me the audio tour. “That was given to me by someone whose mother I helped with breast cancer,” he says, gesturing to a candelabra. “That was from the wife of an Episcopalian priest whom I took care of,” Groopman says, pointing to a stone etched with a psalm.

“Teach us to remember our days.”

Maimonides' prayer hangs on the wall:

“Let me look at a patient neither

as a rich man or a poor man, as a friend or a foe, but let me see only the person

within.”

“To me, that captures what you aspire to as a physician,” Groopman says enthusiastically. I notice a beautiful print with the well-known phrase

tikkun olam:

“to repair the world.” Groopman has a chuckle about this one. “You'll never guess who gave me that,” he says. “Cornell West!” he guffaws, referring to the famed Princeton professor of African-American studies. “I was his doctor when he got prostate cancer, before he left Harvard and he was in the middle of the blowup with Larry Summers. [Harvard president Summers offended West in 2002 when he questioned aspects of his scholarship.] Cornell calls me âBrother Jerome.' This gift shows that he is a very acute observer of who I amâmy identity and my roots.”

There's a Talmudic line quoted on this same print,

“You are not obligated

to complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it,”

which Groopman says he relates to in his chosen trade. “It's that wonderful tension between feeling that it might be overwhelming when you look at the level of suffering, the complexity of biology and medicine, but that you continue to persevere.” He writes often about this friction: the frustrations of illness versus the optimism of medicine, the realities of mortality versus the sustenance of faith. “The way I see religion informing my work is not that it's magical,” Groopman explains. “It's that I'm part of creationâwe all areâ and we are given certain divinely inspired, wonderful gifts which give us the opportunity to prevail. Not necessarily even to survive sometimesâ because we die, we're all mortal. But to endure.”