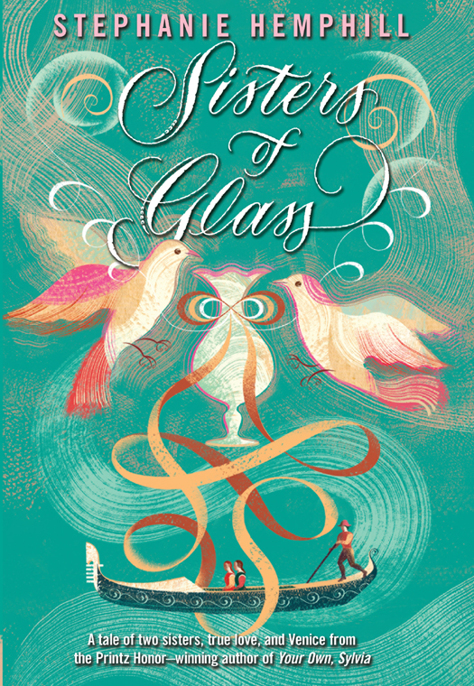

Sisters of Glass

Authors: Stephanie Hemphill

Also by Stephanie Hemphill

Your Own, Sylvia

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2012 by Stephanie Hemphill

Jacket art copyright © 2012 by Anna and Elena Balbusso

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Visit us on the Web!

randomhouse.com/teens

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at

randomhouse.com/teachers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

eISBN: 978-0-375-89701-6

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

For my little sister, Kate

Contents

My Insolence Starves My Family

Full of Feathers, Short of Hair

The Question I Am Not Supposed to Ask

You Can Have That Bumbling Bembo

What to Do About My Father’s Will

AUTHOR’S NOTE

In 1487, the real Maria Barovier, daughter of Angelo Barovier, received permission from the Doge to build a little furnace on Murano for the firing of enamels. She was one of the few women glassmakers of the time and the first known to be granted permission to build her own furnace. This small historical detail inspired me to write this book.

SECOND DAUGHTER

I feel Giovanna’s fire

as Mother prepares me for suitors,

polishes me

while Giovanna polishes glass.

Though I am the younger daughter

and rightfully should

not

marry

into Venetian nobility,

my father declared

the day I was born,

the week he invented cristallo,

that I was his

baby of good fortune,

and good fortune would be mine.

I would marry a senator.

Yet like tides washed into shore

by winds one never sees,

we all prayed

he would change his mind.

We were thus raised

to follow tradition.

Giovanna shoots me

only a sideways glance

as I lace into my new green dress.

I want to scream,

“I will trade positions,”

that I desire to polish glass

and stoke the fires

and see the creation of crystal,

like I was permitted to do

when I was a little girl.

But I promised Father

on his deathbed that I would

honor his first and greatest wish for me.

I just did not know I would

lose my sister even before

I lose my Murano.

MY FATHER, ANGELO BAROVIER

The Barovier family furnace

has molded glass on Murano

for nearly two hundred years, since 1291,

when the Venetian government

required that all furnaces move

to my island home.

The Council of Ten claimed

that it was to prevent fires.

But containing all glassmakers

on Murano also allowed Venice to regulate

her most profitable industry

and to prevent leakage of trade secrets

beyond Venetian shores.

My father spent his entire life

on Murano, never once sailing

into the ocean, not even to Venice.

Father said, “Ships are for cargo,

what need have I of them?”

Besides, he sailed

the vast ocean of his mind,

so indeed, he traveled everywhere.

Father studied to be the scholar

of his family and was to attend

the University of Padua.

My uncle Giova says

he never saw one so eager

to see the world, that my father

packed his bags for university

two weeks in advance.

But fire overtook

one of the two Barovier fornicas

like a thunderstorm.

My father lost his father,

his mother, three of his brothers,

and his only sister

to the torrent of flames.

Father unfolded his clothes.

He and his one remaining brother, Giova,

found work at neighboring furnaces

until they saved enough ducats

to purchase materials for their own.

I always wondered why

my father did not fear

the furnace and the flame,

the hot molten cullet.

He said, “Dearest Maria,

does a general fear a battle

after he loses men on the field?

No. He studies what went wrong,

resolves it, and fights better the next time.

Otherwise, the loss of his soldiers was in vain.”

Not one day

did my father miss work,

even holy days

he created his batches

sundown to dawn.

Angelo Barovier carried

the deaths in his family

on his shoulders

like a mule never relieved

of his load.

I am named Maria

after his sister, who died.

My father died

when I was ten.

Mother wore clothes of mourning

for five years,

until she determined

it was time

to begin grooming me

to be bartered away

from my home.

THE GLASS VESSEL

In some prominent glassmakers’ homes

girls do not work with glass at all,

but my father raised us

to be a family of industry,

all of his children schooled

to understand the art

and business of the Baroviers.

Like first mates to the captain,

we all learned

to prepare ingredients,

to stoke the thousand-degree furnace

with beech and alder wood,

to make his frit,

to polish glass,

and even to blow it.

Giovanna and I

have never been permitted

to blow a punty,

but we understand

how it works.

A well-run vessel,

we naturally settled

into our rightful crew positions.

Father steered and guided the ship.

He remained inventor.

I became his assistant,

lagged after him like a dog,

bobbled carefully

the ingredients for his batch.

My brother Paolo

has blown glass for the Doge,

a master gaffer

my father never saw rivaled.

My eldest brother, Marino,

like my uncle Giova,

dove into business affairs

as though he had been handling

the wicked waves of supply and demand

for a thousand years.

Giovanna and Mother,

both experts at beautification,

polish glass so that our wares

sparkle finer than crown jewels,

so we deliver the premier glass on Murano.

Always servants, hired hands,

workers from other guilds

swabbed decks of the Barovier ship,

for the workload was too great

to bear just us six.

For seven years our two furnaces

alone produced cristallo,

the secret recipe for colorless glass

hidden in the bow of our ship.

But Paolo and Marino

believe that because

Father was stubborn

as a wheel stuck in mud,

our secret escaped.

Father refused to outsource work,

he rather brought laborers into

the Barovier fornicas,

and one must have spied

when Father and I prepared a batch.

Within two weeks

all the major furnaces on Murano

produced cristallo.

We no longer

sat first in church.

Paolo unsheathed his sword

to slay everyone

who worked in our kiln.

Father disarmed him.

“You cannot kill

all the innocent

to avenge the guilty one.”

But after his recipe dispersed,

my father lost

the jaunt to his step

and seemed always

to press a hand over his heart.

A year later

we buried my father at sea.

Clutching a clear cristallo cross,

he departed Murano

for the first time,

never to return.

TALENT

A graceless gosling,

I stumble through most things.

Like a baby just learning to walk,

I try to step forward

on my own but usually

fall down bottom-heavy.

Giovanna excels without even trying,

as though she emerged

from the womb a golden child—

fair, gentle, kindhearted, feminine,

and she sings sweeter, and with better tone,

than the finest instrument.

Her voice could praise the Doge,

her singing make God weep.

As she polishes glass

or if gloom fogs the day,

Vanna will step to the window

and sing to lift those who labor

with melody and cheer.

People cease working

and listen. Some deliberately

route past our palazzo

to hear her music.

My voice sounds old

and witchy as crackling flames.

One day Vanna sang

little rippling scales

out the window, and the light

on her hair and cheeks

made her look like a saint.

I grabbed paper and quill

from my father’s old work desk

and drew Giovanna in her radiance,

sketched how she made us all feel

when we heard her voice.