Shorelines (20 page)

Authors: Chris Marais

Tags: #Shorelines: A Journey along the South African Coast

But Oom Manie was in a mood to parley first. Small talk to smooth the transaction.

“I produced the CD because it’s time we also made some money from the perlemoen,” he said. “We all used to eat perlemoen here. You see these two old ladies? Well, they grew up eating perlemoen. That’s why they’re still so lovely.”

We spoke about

boeremusiek

for a while. Our housekeeper, Dorah Sebola, was a Pedi who grew up on a farm in Limpopo Province. Somewhere along the line Dorah must have had

boeremusiek

hard-wired into her system, because she adored it. She was a special fan of the Baardskeerdersbosorkes, and we told Oom Manie so. He literally preened. Warming to us, he finally clicked open the briefcase. The deal was about to go down.

I bought the perlemoen CD and another one produced by the orchestra for R100. Months later, I played the perlemoen one, titled

Manie en Piet Speel ’n Moerse Hou

(Manie and Piet Play one Helluva Shot). It turned out to be a bit of a diamond in the rough. They sang of poachers, long weekenders in a jail cell, paying bail, staging farting competitions and running off with sackfuls of perlemoen. It was all a bit edgy and defiant and ran for just less than 22 badly produced minutes. Even Piet Smit, Manie’s partner in this particular crime, admitted the “pressing wasn’t so good”.

“But they’re flying off the shelves,” said Manie, referring to sales of the album.

“Oh,” said I. “Where are they being sold?”

“From my home,” he replied. “They’re flying off the shelves here.”

I took another sip of my

witblits

.

The label on the bottle read:

“

Suiwer Lawaaiwater. Spookpis Blitz. Een dop en die donder tref jou. Gestook, gebottel en gesmokkel deur … Ons Geheim.”

All of which boiled down to “Very strong booze – we won’t tell you who made it or how.”

“The old people used it for medicinal purposes,” someone said from the darkness. “They had one first thing in the morning. Then a second and a third.”

I looked over at Jules. She took a gentle sip and was propelled backwards out of her chair, eyes bulging, choking and gasping and generally being a girl. Manie & Co were soon falling about the kitchen in high spirits, which prompted Jules to start hamming up the whole affair. I sat there like The Godfather watching a bad cartoon, drinking

witblits

and wondering about the bats in my head. Those black bats.

We had to get out. I wasn’t going to watch a Currie Cup Final with this band of delightful ruffians. So we drove off, with Manie’s words ringing in our ears:

“Remember,” he yelled from the front door. “There are only two things that look and taste like a perlemoen. And one of them is a perlemoen …” How rude. How lovely. Bless the Saturday brandy drinkers of Baardskeerdersbos.

We arrived at the rather plush Arniston Hotel, checked in and watched the Cheetahs have a little Blue Bull for late lunch. I wanted to phone the boys in the band and crow, but decided against it.

We took a drive around the village and found No. 2A, Arniston Sea Cottages, where we had stayed a few years before. It was a huge yet cosy building, complete with fireplace inside and a table outside where you could clean your fish before the

braai

. And then there were memories of the infamous egg-cup saga from the previous time.

It had to do with the Visitors’ Book at No. 2A, which contains an entry from a Philippa H, of London, dated 21/5/96:

“Your understanding of the word ‘luxury’ is different from mine. The cleanliness of the house left much to be desired and the ‘modern, fully-equipped kitchen which caters for your every need’ simply didn’t exist. The plywood fittings are of the cheapest, shabbiest kind. The two saucepans of battered tin and burnt inside were just about fit for a scout’s camping trip, not a modern kitchen.

“The hob and oven in this house are simply a disgrace. As rust is such a problem, why don’t you fit a ceramic hob or gas cylinder? The element is hanging off inside the oven, looking very dangerous. The oven is, of course, filthy. The glasses are smeared, as is the cutlery. No egg cups. How can this possibly ‘cater to our every need’? No phones, not even an internal line to call Reception to say where are the egg cups? The house is draughty, spacious but not comfortable and badly planned. Speaking as someone who helps run a self-catering business in England, you should be ashamed of yourselves.

“Re-plan and re-fit and re-equip the kitchen and clean the house properly (including the windows) and you may well pass the ‘luxury test’ with flying colours.”

We were in the middle of a coastal thunderstorm, sipping Government Port and toasting marshmallows in front of the fire. The cottage was ‘badweather romance’ epitomised. We read some more entries, in reply to the irate diatribe above:

“Egg cups and ashtrays were spotless.” – B Davies, Sydney, Australia.

“The British pioneers who helped to found this land would rightly be turning in their graves could they read the entry of 21/5/96. We are proud to be from Scotland and the north of England, where the positive pioneering spirit is still strong. This is a wonderful complex in our opinion, and in a truly wonderful situation.” – Dr CK Land, Scotland.

“One of the best moments of my seven months in this beautiful, frustrating, amazing country. The uptight, soulless cow who wrote the comments of 21/5/96 has obviously never seen the stars here on a cloudless night – egg cups are irrelevant in the face of such awesome beauty.” – C, from Streetham Hill, South London.

“Please get some real egg cups. I had a boiled ostrich egg and it just wouldn’t fit these piddly little things in the cottage. Had to use a bucket.”– The Easter Bunny.

And then they just got downright crazy:

“Tried to burn the thatch, but it’s obviously treated. Managed to carve my name under this table, though.” – Eric E (no origin).

“It’s bizarre how things turn out after a long, extremely stressful, difficult year in Johannesburg and my marriage on the rocks. K and I came here with the hope of getting away from it all and trying to get back some of that head space we once shared. We arrived, took loads of drugs and fucked all day and all night! Try it, sports fans, you won’t believe what it does for the soul.” – GB (no origin).

We drove on to the true end of Africa, Cape Agulhas. A

witblits

headache was beginning to storm inside me. We found The Southernmost Café In Africa, bought a couple of KitKats and walked past a lonely fairground pony nearby.

“The more you think about life, the more you feel it is thinking about you and reaching out to you as you reach out to it,” a disembodied voice to my left suddenly intoned. I was amazed to see it was Jules. And in a serious mood.

“You realise you can touch holiness at any time. It is always there. Eventually everything is holy, and your will to see it is granted. The more you give up, the more you gain. Your vulnerability and openness make you stronger than steel.”

I could not think of a single wise word in reply. Instead, I came out with:

“Do you think we’re currently staring at the Southernmost Fairground Pony in Africa?” And left it at that …

Arniston and Elim

It’s 30 May 1815, and a thick fog has set in on the coast around Waenhuiskrans in the Overberg about 40 km north-east of Cape Agulhas.

The British East Indiaman called the

Arniston

is approaching the coastline in convoy. Most of the passengers on board are wounded British soldiers from six regiments stationed in the East. A squall brews off the Agulhas Bank and the resultant hurricane drives the

Arniston

towards the land. By dawn, it is clear that the ship lies in the eye of a storm, surrounded by breakers.

Taking the advice of his staff and a Royal Navy agent on board, Captain George Simpson heads the vessel towards land, hoping to beach her. The

Arniston

, according to reports, hits a reef more than 1 km out at sea and begins to break up.

It later emerged that Captain Simpson had mistakenly taken this part of the coast for Table Bay, but once the currents began dragging her towards the beach it was too late. Among those who drowned were 14 women, 25 children and Lord and Lady Molesworth.

We found a plaque near the beachfront that read:

“Erected by their disconsolate parents to the memory of Thomas, aged 13 years, William Noble, aged 10, Andrew, aged 8, and Alexander McGregor Murray, aged 7 (the four eldest sons of Lt Col Andrew Giels of HM 73

rd

Regiment) who, with Lord and Lady Molesworth, unfortunately perished in the

Arniston

transport, wrecked on this shore the 30

th

day of May, 1815.”

The “Sale Notice Of Goods Salvaged From The Transport Ship

Arniston

” read:

“[A] quantity of Goods, saved from the Wreck … consisting of:

“122 Casks, containing Wine, Arrack etc;

“580 empty ditto, of different sorts;

“1 Bellows;

“2 Casks Pitch and various pieces of Cordage and Rattans.

“The Sale will commence at 10 o’clock in the morning of each day, and be held on the Beach near the Eilands Valley Caledon, 23

rd

of July, 1815.”

This part of the coast was home to

Strandloper

communities as long as 120 000 years ago. Shell middens have revealed bone fish-hooks, stone sinkers, sheep bones and clay pots, evidence that Khoi herders lived here as well. These days, the village of Arniston (which was formerly called Waenhuiskrans) boasts houses that are being sold in the R5-million bracket. Cape Town uses Arniston as a weekend getaway, and we soon found out why.

After four weeks on the coastal road, Jules and I collapsed gratefully into the world of the Arniston Hotel, a welcoming universe of excellent showers, a great double bed, satellite television, room service offering fresh kob, vegetables, baby potatoes and ice-cold lager. That night, after delighting in the total nonsense of a Hollywood teen-thriller movie, we literally passed out. Jules dreamt that a Lambert’s Bay gannet had become our travelling companion and, when there was no fresh fish, it was happy to be fed bread soaked in milk. I always marvel at the exquisite detail of my wife’s dreamtime.

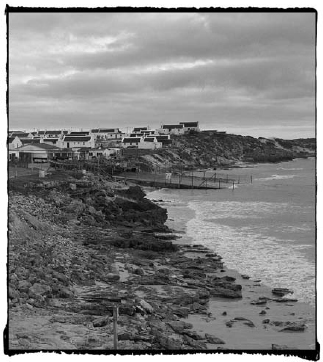

In the morning we breakfasted on homemade bread, smoked salmon, cream cheese, a fruit fantasia and pots of strong coffee. And then we walked up to Kassiesbaai, the fishing village on the hill that gave Arniston all its seafaring appeal. In a bid to keep developers at bay, so to speak, Kassiesbaai had been declared a national monument.

We heard that there’d be a service at 10 o’clock at the little Anglican Church in Kassiesbaai. For some strange reason (we are not regular churchgoers) Jules and I both wanted to attend, so we rushed back down the hill to get properly dressed.

We sat at the back of the simple building, which was soon quite full. A few women, their heads covered, came in, genuflected and crossed themselves.

Outside, five girls in red-and-white smocks waited for the service to begin. One of them twirled an incense burner over her head, as if it were one of those fire-dancing tools you see at trance dances.

At ten exactly, with an air of great ceremony, three priests walked in, led by the altar girls bearing crosses, candles, the holy communion wafers and a small bell.

It was Holy Eucharist, and Father Eli Murtz led the service. His message revolved around the story of the Good Samaritan.

“Take a good look around,” he said. “See who your real neighbour is.”

Perhaps he had noticed the two pale faces at the back of the church, because he continued:

“We have to help people of all races and backgrounds, and see everyone as our neighbour.”

We prayed for the community, and the priests asked the parishoners to remember Americans suffering in hurricanes (Katrina having recently had her way with my New Orleans) in their prayers.

They also offered a special prayer for anyone who wanted to come forward for a particular reason. A man asked to have his young son specially blessed because it was his birthday. The priest prayed with his hands on their heads.

There was a slow build-up to the drama of the Holy Communion. First there were readings. The priest was surrounded by the altar girls, who held up the Bible, illuminated it with candles and held a cross high.

The incense was lit, and the burner swung back and forth. The priests gathered round the small altar. A woman holding up the book from which Father Eli read rested her hand over her heart.

The spiritual tension kept building. The community had now completely forgotten about us, and was entirely focused on the tableau before them. There was a hushed reverence. The church had become wreathed in incense and was lit with candles and fervent, almost-tangible prayer.

The people gave the moment their full attention, and breathed its holiness. Everyone was uplifted at the moment Father Eli held up the Host, and one of the altar girls rang a bell.

The singing after that was joyous. It was not just another ‘Kumbaya moment’. In layman’s terms, it rocked.

Everyone around us reached out to shake our hands, and we smiled shyly at one another. Peace. Peace. Peace.