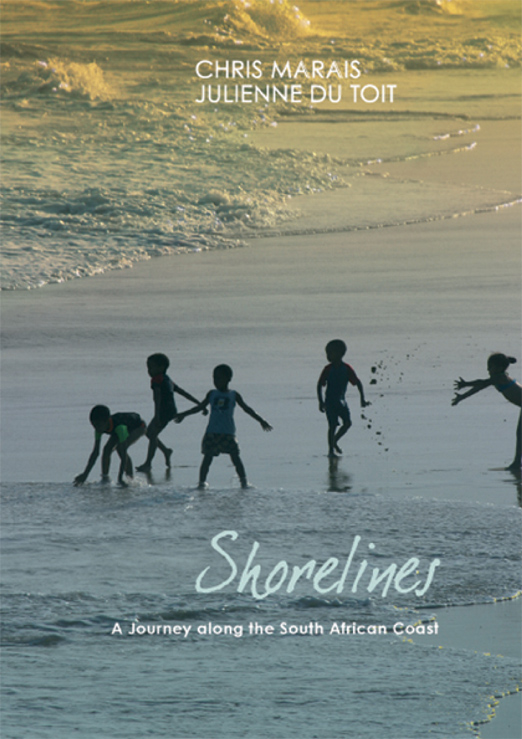

Shorelines

Authors: Chris Marais

Tags: #Shorelines: A Journey along the South African Coast

A Journey along the South African Coast

We would like to thank everyone who gave us shelter, time and information along our journey.

Shorelines

is dedicated to the people who live and work at the water’s edge in South Africa.

Chris Marais & Julienne du Toit

Chapter 3:

Khubus to Port Nolloth

Chapter 5:

Hondeklip Bay to Doring Bay

Chapter 7:

Elands Bay to Paternoster

Chapter 8:

Velddrif to Cape Town

Chapter 13:

Masiphumelele to Pringle Bay

Chapter 17:

Gans Bay to Arniston

Chapter 20:

Mossel Bay to Knysna

Chapter 21:

Plettenberg Bay to Keurbooms Strand

Chapter 23:

Storms River to Jeffreys Bay

Chapter 25:

Port Elizabeth to East London

Chapter 26:

Morgan’s Bay to Trennery’s

Chapter 27:

Trennery’s to Umngazi River

Chapter 28:

Port St Johns to Mbotyi

Chapter 29:

Mbotyi to Port Shepstone

Chapter 32:

St Lucia to Kosi Bay

Everywhere in the world, big things happen at the edge of the sea. It is the ultimate borderline between earth and water – a place of energy and change.

In South Africa, life along the coast is particularly dramatic – in many ways. More than 3 000 ships have come to grief on its rocky shores over the centuries. ‘First Intelligence’ wandered about here, leaving footprints and eating limpets and abalone. Later, the children of

Strandlopers

picked beautiful river-rubbed diamonds from its north-western beaches and kept them as baubles. Today, most South Africans dream of living near the water’s edge, where something like one-third of the country’s GDP is said to be generated. A better life, they believe, awaits them at the shoreline. Sometimes, however, it’s

harder

to survive down by the sea.

In the early summer of 2005 we set out on a 70-day trip that would span the 3 200-km coastline from Alexander Bay at the southern edge of Namibia in the west to Kosi Bay on the Mozambican border in the east.

Jules and I moved from landscape to landscape, village to village, issue to issue – but mostly from face to face. Sometimes, to get the coastal perspective right, we’d have to wander inland to places such as the Richtersveld, the Agulhas plain and deep Zululand. In the big cities, we chose cultural encounters: Long Street in Cape Town, the townships of Port Elizabeth and the Inner Zulu experience of backstreet Durban.

Along the way, we were often tempted to throw a stick of dynamite at some of the monstrous coastal developments we encountered – bad taste hard at work with its little face-brick fantasies. And believe us when we say Squatter Camp Chic is sexy only in distant photographs. Up close and in the rain, it loses all its charm.

Excessive wealth is just as offensive as desperate poverty. We saw too much of both in our journey – “golf balls rattling into tin cups to your right. And beggars rattling tin cups to your left …”

That’s the social storm warning of

Shorelines

. The rest of the recollections are things we found funny. And breathtaking, especially in the form of a visiting southern right whale showing off her new calf in Walker Bay. Or a moment touched by holiness in a fisherman’s chapel in Kassiesbaai. Or a flight over pristine blue waters along the Wild Coast, with more than 1 000 common dolphins at play down below. There is great beauty and wondrous humanity along our beaches and cliffs and crags, where the sea meets the land.

Wherever we went, we made new friends and learnt new things. We fell in very briefly with diamond divers, surfers, skippers home from the sea, fishermen, second-hand bookshop mavens, all sorts of developers, Rastafarians, Cadillac collectors, forest adventurers, Transkei nannies, sushi chefs, Zulu shield-makers, abalone poachers and their pursuers, shark-diving enthusiasts, golfers and greenies.

We heard about mice that surfed the waves, baboons so clever they were “one good Food-Channel programme away from baking their own bread”, a young woman who choked to death on a giant oyster in the middle of her wedding feast, diamond smugglers who used pigeons as flying mules, barrels of ancient rum tossed up on the beach, a Maasai warrior who walked from Kenya to Cape Town, and millions of delicious lobster that occasionally strode desperately from the sea. We went where crocodiles walk the beach, leopards stalk the shores and ghosts of castaways stumble into the mist.

We renewed our acquaintance with South Africa’s Robinson Crusoe, Ben Dekker of Port St Johns, who sent us this letter once we’d returned to Jo’burg:

Chris & Julienne,

About this coastal travel book you are busy with. I’m a slow thinker and it takes me a while to work out the thinking of listeners when I am doing most of the talking.

I have always been attracted to the people that travellers bounce off and describe – after having revealed enough of themselves to make the reader interested in their opinions. The places are secondary and only get real meaning from the people who inhabit them.

Does one not really travel from person to person, rather than from place to place? Even when you have found such in-tune travel companions as the two of you have?

Think about it. Might give a nice new angle to your book.

Ben.

Chris Marais & Julienne du Toit, March 2006

Johannesburg

Alexander Bay

A rotund little homing pigeon sits in swirling mist on a road somewhere in Alexander Bay, looking upwards at the Richtersveld skies with pleading eyes, flapping his wings. But he’s carrying 50 uncut diamonds taped around his chest and his tiny flying muscles can’t manage the extra weight.

Approaching fast is a police officer, and you can hear his heavy tread on the tarmac. The bird, on the lam with nearly US$10 000 worth of stones, is a picture of guilty anxiety as it launches itself into the air, rises no more than a metre and flops back onto the road. It’s like the Getaway Car That Couldn’t. The officer, spotting the contraband on the pigeon’s undercarriage, takes aim with his service rifle. The shot can be heard for miles down South Africa’s mother river: the Orange.

Flame-winged flamingos shrimping at the river mouth share dark, knowing looks with dapper little avocets wading in the shallows. The kelp gulls, dressed like casino heavies in city suits, gaze philosophically out at the gunmetal waves of the heaving Atlantic Ocean. They know exactly what’s gone down. Rotten luck, old fellow. See you up at the Birdy Gates.

Early in September 2005, at the start of the

Shorelines

journey, Jules and I drove up the old ‘Seven & Sixpence’ Highway from Port Nolloth to Alexander Bay, with Carlos Santana on the radio and a great 10-week coastal caper in our sights.

What an extraordinary thing this was, to start a long journey from an outpost such as Alexander Bay, on the border with Namibia, with the prospect of ending it 3 200 km away on the other side of the continent, facing another ocean, at Kosi Bay.

As we arrived on the outskirts of town, the sun gave the earth a lusty good-morning kiss, leaving a pink lipstick smear on the horizon. I thought of the old-time Namaqualanders, poor as roof rats, building the smooth road over which our ever-trusty, ever-dusty, diesel

bakkie

was gliding. They couldn’t get jobs in the new, fenced-off diamond fields, so they worked here for seven shillings and sixpence a day.

These men could sense millions of pounds’ worth of diamonds lying under their feet. Many of them believed those diamonds should belong to them – the sons and daughters of this harsh country, who had endured more than a century of hellish heat and dust to shove their roots into the land.

But let’s go back, briefly, to our luckless pigeon, who by now was a mess of bloody feathers on the otherwise pristine main street of Alexander Bay. In the late 1990s, pigeons were smuggled into the restricted diamond fields of Alexander Bay, loaded with stones and sent on their way home, where willing hands would relieve them of their precious loads. It was such a ridiculously simple trick that it actually worked for a while.

In fact, when we ran this scam by some

bona fide

pigeon fanciers later, they scoffed and said:

“A serious pigeon breeder who wanted to smuggle diamonds would simply make them eat the stones, let them fly home and then give them a small pill to empty their innards.” Just as I thought.

An uproar erupted in the South African Parliament when it was announced that Alexkor, the government-owned mine at Alexander Bay, was losing US$200 million in stolen diamonds each year, most of them “strapped to well-trained homing pigeons”. The order went out, arrests were made and various homing-pigeon clubs (which, ironically, had been given start-up funds by Alexkor) were closed down. More than 900 birds were given the boot.