Shorelines (3 page)

Authors: Chris Marais

Tags: #Shorelines: A Journey along the South African Coast

“Cars are his obsession,” said Helené. “On his third birthday, he asked me for a driver’s licence.” We drove to the Gariep (formerly the Orange) River mouth, a traditional party spot for the locals. On the way, we passed pink lagoons packed with thousands of flamingos. Jackal tracks and the odd flamingo feather on the sand told us there had been some bird predation in the night. The rain pelted down, we ran for the vehicle and Helené discovered she was low on gas. So that’s how we ended up in one of the mining villages outside a friendly household where she went in to secure a lift to acquire more fuel.

Young Gideon, in the meantime, used this opportunity to hop into the driver’s seat and practise. He adjusted the rear-view mirrors, fiddled with the indicators and shifted gears. Jules and I watched in discreet horror from the back seat. Was this tot going to abduct us? A true kid-nap? Was he going to drive us into the sea? Just as he was beginning to toggle at the ignition keys, his mom returned to say she wouldn’t be long now.

“Do take him with you,” we urged.

Helené lifted Gideon out of the Land Rover and we were saved. To us, Gideon will forever be, in the true tradition of Alexander Bay nicknaming,

Vroom Vroom

Mostert. It was no strange thing in the old days to stand about at the security gates of the mine and hear the guards greeting fellows called

Beeskalf

(bullock),

Ystervark

(porcupine),

Peperhout

(pepper tree wood),

Spook, Bokram

(billy goat),

Regterbeen

(right leg) or

Linkerbeen

(left leg). Each of these names had some sort of a background, part of the legends of the thirst lands.

The rains moved on up the coast to Angola and in the late afternoon Helené took us to her favourite spot in all the Richtersveld: Lichen Hill. It’s an extraordinary outcrop of very clever little plants and lichens that live off coastal fog. She showed us how cunningly these odd-shaped plants hid from the sun.

We found ourselves in a world of succulents, stone flowers, window plants, lizards’ tails, euphorbias and Bushman’s candles, which have pretty leaves that harden to form sword-like thorns for defence. It suddenly flashed on me.

“Jules, I think I know why Fred Cornell never found diamonds up here. He was too busy with the other stuff. Like this stuff.”

But one man’s seaside resort is another man’s Siberia. If you were a cop, a 12-month stint at Alexander Bay was seen as punishment duty.

It was well past my bedtime at the Frikkie Snyman. Jules was fast asleep and I was having a small whisky. I was also reading what initially looked like a boring company hagiography called

Baai van Diamante

(Bay of Diamonds), commissioned by Alexkor and written by Pieter Coetzer.

I soon discovered Mr Coetzer to be some kind of genius, and a hardworking one at that. He delved deep into the history of Alexander Bay and interviewed more than 300 people who had lived, worked and fished here. I needed the help of a few more drinks to cut through the company bumph and then, as on any successful fact-prospecting mission, was rewarded with a rich seam of anecdote. I don’t know if he’s aware of it, but Pieter Coetzer is sitting with a cracker of a travel book. Something as potentially charming as

The Glamour of Prospecting.

In his chapter on the policing of Alexander Bay, entitled

Die Lang Arm van die Gereg

(The Long Arm of the Law), Coetzer says that the first lesson taught to tenderfoot cops was that wine, women and song were off limits up here.

“This is a chance for young men to pay off debts and let bank balances grow,” the commanding officer would bark at them on parade. For which, one obviously reads:

“There’s bugger all to do up here. Stay sober, do your job and save your salaries.”

So you had the cops on one side, protecting the State’s diamond interests and living like slightly pickled sand rats dreaming of home postings. On the other, you had Namaqualanders of all hues, who felt in their hearts that the diamonds were really their birthright. Hmm. An interesting scenario, in anyone’s books.

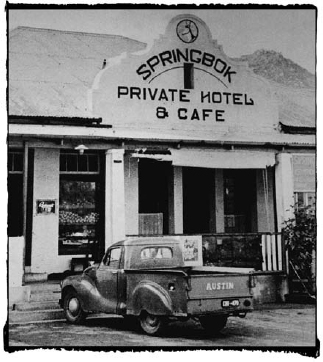

What did the naughty Namaqualanders do? They stole. They smuggled. They finagled and they schemed. You couldn’t keep them down. The minute you bust them on one scam, another would raise its meerkatty head. Jail them, and they would be hailed as local heroes the minute they walked out of prison. They kept fast cars (the Austin Baby was the getaway favourite in illicit diamond buying) that could skim over the skanky roads like boatmen over stagnant pools, while the police lumbered behind in State vehicles.

The cops then bought a fleet of Austins to keep up. So cheeky were the smugglers that they stashed diamonds in the radiator of the district commandant’s official car. And when this car was sent down to Port Nolloth for repairs (for these were the new regulations), it came back a little lighter. But the ‘repairmen’ also made sure that the DC’s vehicle had something else wrong with it. Pretty soon, it would have to return. Probably with more diamonds in the radiator, right under officialdom’s nose.

If you were the South African government trying to keep control of diamond stocks so the market would not be flooded, all this to-ing and fro-ing over the fence was no joke. Very few law enforcers officially found it amusing when one man trained an ostrich to wait for him on the other side of the fence, pouch the flying bag of diamonds like a good slip catcher and then stride off home with the booty. Of course, the impoverished, sunken-eyed majority of hard-bitten Namaqualanders toiling on the Seven & Sixpence Highway dined off that story for years.

They stuck diamonds in their legs, in the heads of sheep, in the heels of their shoes, behind eye patches and up their noses. There’s the famous story, told to us by someone down south, of two brothers who worked at Alexander Bay, one in the

binnekamp

and one in the

buitekamp.

“Both smoked a pipe. Every week, they were allowed to see one another in the visiting lounge, so they devised a plan to use identical tobacco pouches. The one coming from the inside brought the diamonds, the other took them home.”

And we mustn’t forget our lonely little pigeon with the excess baggage, trying to take off from the main street of Alexander Bay.

We left Alexander Bay before the sun came up, heading east along the Gariep after a mandatory stop at the SA–Namibia border post to signal the official start of our

Shorelines

adventure. The full stop on the trip would come months later, when we were in sight of the SA–Mozambique customs offices north of Kosi Bay.

Near dawn, we were at Beauvallon, a lush Alexkor farm. I went over to the fence to photograph a couple of male ostriches that boomed at me like plumed lions. We saw a sign that read: Grootderm Handelaar.

Jules was oddly fascinated by this nowhere spot. “How would you like to work in a shop called Large Intestine Retailers?”

The ostrich tried to eat my 18-125mm lens. When I wouldn’t let him he flounced off in the direction of some girl ostriches and began writhing and thrumming his neck in pleasure in front of one of them, fluttering his black and white wings like a feathered Folies dancer somewhere in the Pigalle district of Paris, where the red lights mean ‘go’.

The object of his desire, meanwhile, looked like a drab, grey feather duster pecking absentmindedly at the ground.

“Come play,” he said to her in ostrich-mime.

“I’m busy trying to eat this stone,” she replied in same.

“Let’s make love,” he persisted, whirling in his fandango, a blur of wings and lascivious looks. How

could

she resist?

“Naah.” No nookie for Mr Fabulous today. We thanked them for the show and continued to Brandkaros, a huge citrus farm and tourist camping site on the river. The heady aroma of orange blossoms hit us.

“It smells just like happiness,” beamed my wife.

Driving on, we saw reckless 4x4 tracks heading over the delicate terrain. Then we passed ruined landscapes where the mining companies had had their way. It struck us that these post-Apocalyptic heaps of tailings would be perfect 4x4 playgrounds. If the muscle-car brigade went

there

instead, the vulnerable succulent deserts of southern Africa would be eternally grateful.

We arrived at Cornell’s Kop along the Sendelingsdrif road to the Ai-Ais/Richtersveld Transfrontier Park. I was thrilled to see something named after our Fred at last. The hill is ringed with rather exquisite false quiver trees, some of the last of their kind left in the world. Somewhere around here is a deep hole allegedly connected to the Gariep River, through which the Big Snake occasionally meanders. The monster, often spotted at the Augrabies Falls in times gone by, is said to rule the river. I do not possess a fondness for snakes, so I wasn’t keen to find this hole.

We’d strayed inland to flesh out the facts behind an astounding land claim that promised to shake the foundations of the South African mining world. The Richtersveld community of nearly 5 000 souls, mostly diamond workers and roaming herders, had claimed 85 000 hectares of mainly coastal land in the Northern Cape that had been taken from them in the 1920s when diamonds were discovered. The claim area included the Alexkor fields. The claimants not only wanted the land returned to them, but also more than US$200 million for diamonds extracted over the eight decades of the mine’s existence.

A 75-year-old Nama elder, Oom Gert Domroch, stood up in the Land Claims Court in Cape Town and, through an interpreter, said:

“Among our people, there is nothing like this taking away of land. You may not take away someone else’s thing. You have to ask. I remember it as it was told to me by the old people. There was no discussion, no negotiation. It was simply taken away.”

“What should be done to put this right?” asked the community’s attorney Henk Smit.

“I think the person who took a thing from you must put it back,” the old man replied. In October 2003 the Constitutional Court declared that the Richtersvelders had a right to restitution and compensation. At the time of writing this book, the claim was still unresolved. To outsiders, it seemed the government was playing a waiting game of ‘Who’s Got The Deepest Legal Pockets’ with the claimants.

“We will not drive around with Mercedes-Benz cars,” said one of their spokesmen, Floors Strauss. “We will not give cash handouts. We’re going to use the compensation to make sure that we will provide jobs, educate our youngsters and develop a sustainable Richtersveld.”

And by God, didn’t the Richtersvelders need a diamond dollar or two? That was the gist of our thoughts as we rattled into Khubus, a dusty mission settlement in the east. A car wreck lay upside down at the entrance to the village. At the Tourist Information Centre, no one had time to guide us. We were briefly told that half the people in Khubus had no jobs and that the church was a nice place to visit. But Tommy Thomas back in Alexander Bay had given us the name of one Willem Slander, so we made enquiries and ended up knocking on the door of his house.

We heard muffled voices and clicking and muttering on the other side of the door, as if dozens of safety locks were grudgingly being opened. A small, wizened man in a Toyota cap peered around the corner. He emerged from the dwelling, closing the door firmly behind him as if there were a secret life inside, a no-go zone for us strangers.

“It looks peaceful out here,” remarked Julie, trying to kick-start a conversation.

“Not so peaceful,” the old man said. “If the wind wasn’t blowing so bad, you’d see the kids up there on the hill, lighting up.”

“Lighting up what?”

“Dagga, Mandrax, even this new Tik thing.”

I shuddered. For the dreaded crystal methamphetamine (street name: Tik) to have made its way so far north was a shock. It has a 94% addiction rate, induces psychotic behaviour and is often used by gangster gunmen just before a hit.

“It has also been called ‘Hitler’s Drug’ because it was allegedly used by the Nazis as a combat pill to fuel aggression and help soldiers stay awake and remain focused for long periods,” say researchers at the SA Institute for Security Studies. The Tik Generation? Up here, in lonely Khubus?

As we scuttled out of town, a youth wearing a baseball cap bearing a stitched-in marijuana-leaf emblem stepped into the road and stopped us with an imperious air. Were we going to Sanddrif? No, we were heading south to Lekkersing. Where were we from? What were we doing here? The slurred questions came thick and fast. Who was he, we countered. And what was that on his cap?

He smiled and said something vaguely Richtersveld-Rastafarian:

“

Die Aja Baas

.” The Big Holy Boss. He had a dead look in his eyes. You just knew. No amount of diamond paybacks would ever bring a sparkle back to them again …

Khubus to Port Nolloth

I have lived with this image of the Richtersveld for decades. It is the portrait of an aged woman, perhaps old before her time. The face is plump and folded, the smile is gaptooth-marvellous, the eyes are squinty yet glinting with humour. The whole delicious array of facial features is framed by a faded pink bonnet, standard headgear for the Dames of the Dry Land.