Shorelines (8 page)

Authors: Chris Marais

Tags: #Shorelines: A Journey along the South African Coast

After visiting the gannets, we returned to the mainland, fell on a lunch of fish and chips like wolves (those wolves, obviously, who eat fish and chips) and remembered a previous visit to this place, when the air was thick with the stench of fish being processed. We mentioned this distinctive aroma to restaurateur Isabel Burger, whose husband worked at the fish factory.

“That smell? That’s the smell of our money.”

The real smell of money around here lay in the ‘chips’ side of the fish-and-chips business. There were more potato farmers up here in the

sandveld

than you could shake a dipstick at. Those very farmers were having a potato convention in Elands Bay when we chugged into town and took up temporary lodgings at

Die Bottergat

(The Butter-bum).

“Pin a tail on me, call me a weasel,” Jules kept chanting (this, for those who don’t know, is her ‘I’m Very Impressed’ song) as she moved through the charming little traditional cottage. She raved over the succulent garden outside, the massive hearth inside, the quaint family photographs on the walls, the bottles of Voortrekker Inflammation Oil and Cape Dutch Chest Drops, the paraffin storm lanterns and the yellowwood cabinets. From the rafters hung bunches of dried flowers and tumbleweeds and mobiles and decorations made from sea-urchin shells and bits of motherof-pearl. We could picture happy families here, on rainy days, working away at these mobiles.

But why the name, we asked the caretaker, Hentie van Heerden.

“A Mr Van der Westhuizen bought the plot in the old days for next to nothing and built this cottage,” he said. “When his children inherited it, the place was worth a small fortune. They said they had landed ‘with our bums in the butter’. Hence the name.”

The waves at Elands Bay, Hentie said, did more than occasionally cough out tonnes of lobster.

“It’s a great surfing spot. The waves form a left-hand tube that spits you out in the general direction of Lambert’s Bay.” A left-hand tube? Mmm. As opposed to a right-hand pipe? The wondrous world of surf-speak still lay before us like a foreign country.

“How about some snoek, then?” suggested Jules, and off we went to the Elands Bay Hotel. On the porch, two ravenous surfers stood devouring large quantities of sandwiches, chips and coffee, gazing intently out at the waves. That left-hand tube thing again.

The snoek was fresh and firm and very tasty. It has always been my favourite fish, mainly because it has big bones that you can see and extract right away. None of that Sneaky-Pete, barely visible, skinny-bone shit that sticks in your craw and makes you search your own gullet with a mirror and tweezers in the dead of night. Snoek is honest eating. I like snoek.

We had questions for Celeste Kriel at Reception. Firstly, what happened to the tail of the fat hotel dog? Secondly, had she ever seen a snoek run?

“That’s Kisha. We’ve tried to put her on a diet but it doesn’t work. Her tail was bitten off in a fight, back in the days when she still could move around.

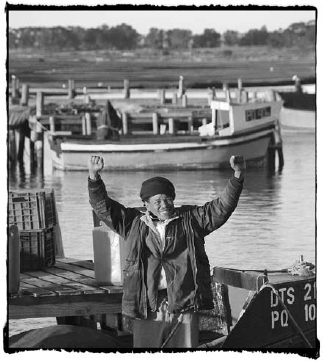

“I’ve seen a snoek run, believe me. In August the snoek ran for the first time in many years. You could not believe the excitement. I just had to drop everything and run to the beach and watch. The fishermen were hauling in snoek after snoek, singing and laughing as they worked. It brought tears to my eyes.”

We promised Celeste we’d return that evening for drinks at the bar. Heading out to Leipoldtville for the afternoon, Jules and I came across a couple of Xhosa fishermen and their slim pickings of

hotnotsvis

. Simon Mxeba and Themba Metu had come here more than 30 years before from the Transkei to fish – and simply stayed. They were far from home. Hentie told us earlier that when the Xhosa workers were first shipped over to the West Coast to begin their new careers as fishermen, they were taught to row the little skiffs in Verloren Vlei. Over the years, they became expert fishermen, plying the Atlantic shoreline off Elands Bay like salty sea dogs.

“For better or for worse, this is now our home,” they said. The West Coast had crept into their souls.

We continued past swathes of potato farms eating up the

sandveld

(and not in a nice way) into the quiet village of Leipoldtville, named for the father of C Louis Leipoldt, the legendary man of letters. And of cooking, as my travel mentor, the late Lawrence Green, writes. In

On Wings of Fire,

he says Leipoldt liked to eat hippo meat,

dikkop

stuffed with orange, breast of flamingo, lizard, squirrel, hedgehog, giraffe tongue and pickled swallow. Regular ‘critter cuisine’. I wonder what he would have thought of Reynold van Wyk’s

bokkoms

back at the bar in Doring Bay?

Elands Bay to Paternoster

I’m at the top of a hill overlooking the sweep of Elands Bay, a sunset spot of note. I can see a pink mist of flamingos wheeling and turning towards the reed banks of Verloren Vlei, a clutch of surfers catching the last waves of the day and the Piketberg rising in jagged lilac relief on the far horizon. I can even see the Fisheries Compliance Officer in the distance, arriving at his tiny shack. He is probably the most closely-watched person in Elands Bay. Everyone always knows where the Fisheries Man is – at any time of the day or night.

Jules is not far away, deeply involved with a

sandveld

succulent. We’re going down to have a sundowner shortly, and all is well with our world.

Then my cellphone thrums like a beating heart and an SMS comes streaming through:

“It’s Teazers teazing time @ Teazers nationwide. Free entry 6/10 & 7/10 till 7pm. Book ur table. New girls call 084TEAZERS 2 view. Don’t speed 2 ur nearest branch.”

“Who was that?” asked Jules.

“It’s Teazers. They want me to come over for a lapdance.” I was on their mailing list. Somehow my business card had found its way into one of their clubs. It must have been while I was doing a story or something.

“No titty bars for you, young man. We’re going drinking,” said my stern yet wise wife.

We arrived at the Elands Bay Hotel in the midst of Happy Hour, where a potato farmers’ convention was in full swing. The potato heads all turned and looked at us as we arrived, saw we couldn’t possibly be potato industry inspectors and continued making small potato talk while watching the ubiquitous Paris Hilton on TV with the sound turned off and the Eagles singing ‘Hotel California’ very loudly on the sound system.

“You know, I sometimes worry about Paris,” I told Jules over the din. “When

is

that girl going to get a real job?”

Unbeknownst to us, there were serious issues at play here among the potato conventioneers.

In some places up here in the semi-desert, the water table had dropped by as much as 14 metres and was below sea level. This meant salt was being drawn through the soil and was turning the borehole water brackish.

In 2005 the Verloren Vlei – the most prominent wetland in the area – was in trouble. Water levels were sinking. The reason? Overextraction of water by the potato farmers.

An interviewee in an article in the

Cape Times

of May 2005 remarked that it was like “exporting water inside potato peels”.

“Everyone is losing,” said Rina Theron, Potato Farmer of the Year (2000). “The water and the

sandveld

are vanishing, the farmers are struggling, retailers are forcing us to accept prices below production cost and the middlemen are ripping off consumers.”

Even the potatoes themselves were losing. They had become prey to half a dozen malicious viruses.

“My fellow farmers fail to see the problems for what they are,” Rina continued, when Jules contacted her later. “When the water quality and quantity decline, they just say ‘Next winter the rains will be ample and the boreholes will fill up again.’ It’s gone beyond that now. We need to work on a holistic solution. Farmers need to plant fewer potatoes for a better price.”

No one mentioned the possibility of growing something else. Or doing something with the last vestiges of

sandveld

magic, which lay in the rearing shadow of the distant Piketberg, the huge blue gums and the old reed-thatched homes, in the tang of the sea overlaying the grace of vlei and water lilies.

After a brace of cold beers and Old Brown sherries served in no-nonsense wine glasses filled to the brim, Jules and I relaxed and became one with the pub. Kurt Petzer, the barman, told us that the locals used to come in here and shoot holes in the wall for target practice. But the

pièce de résistance

of the Elands Bay Hotel bar (won’t someone please give it a name?) was the prosthetic leg hanging from the ceiling. With a cap belonging to a Cape Stormers fan swinging jauntily from the toe.

“That belonged to a guy who used to drink here,” said Kurt. “He ran a tab at the bar, and if he couldn’t pay up he’d leave his leg behind as surety and take himself home in his wheelchair. Unfortunately he died without settling his tab, so the leg still hangs there. I don’t know what a second-hand false leg is worth these days.”

“One helluva conversation piece,” I said, and snuck in a little shot of Jack while Jules wasn’t looking.

We took the small two-person party back to our lodgings. The next morning I pushed the alarm button instead of the light switch and all hell broke loose in

Die Bottergat

. Fifteen minutes later we were on the road out of Elands Bay, in disgrace and sucking on tins of iced

rooibos

tea while nursing industrial-sized headaches. We passed the flamingos of Verloren Vlei amid much bickering, hooting, trumpeting and honking. The birds made a bit of a noise as well.

By mid-morning we were moving through our first densely developed coastal zone, a place called Dwarskersbos. Huge billboards selling dreams off-plan shouted down at us. “Own the Beach” vied with “Have a Whale of a Time” and “So Much to Do and So Much Time”, an interesting deviation from the last words uttered by Cecil John Rhodes on his deathbed.

By lunchtime we were gulping down snoek at the Laaiplek Hotel on the Berg River. I read to Jules from Lawrence Green’s

On Wings of Fire

, which in turn was quoting from the journal of a German traveller, Dr Martin Lichtenstein, who had discovered his first Bushman woman at the Berg River, skinning a hare:

“The greasy swarthiness of her skin, her clothing of animal hides, as well as the savage wildness of her looks and uncouth manner in which she handled the hare presented altogether a most disgusting spectacle. Now and then she cast a shy leer towards us.”

“Wethinks the man protests too much,” was our consensus of opinion. Perhaps, like many Africa travellers caught lusting after ‘a dusky maiden’, the good doctor had been away from the home fires too long. Besides, no one in living history – or on any of the shows on the Food Channel – has ever managed to skin a hare elegantly. Flaying wabbits is not easy on the eye.

After lunch, we drove over to Harbour Lights, a self-catering establishment owned and run by René Zamudio, whose family line ran rich with legends of the West Coast and beyond. René himself had a colourful sea history. He was regarded as a pioneer in the pelagic-fishing industry, having plied the waters from Guinea Bissau and Morocco to Australia and the North East Atlantic. And now, after three decades at sea, he had come home to Laaiplek. And he didn’t miss his life on the ocean for a moment.

“You must be here for the Stephan story,” said René, a tall man of 70 years, with eyes that constantly scanned the horizon in the way of a retired skipper.

Stephan? At that stage we had no idea what René was talking about. So we sat on the stoep outside our room and talked over a tin of cold

rooibos

tea. Just in front of us was moored a small lobster boat, with rafts of seabirds lazing on the jetties. Upriver lay the port, with all its fishing boats. Above us the gulls and terns cavorted, while kingfishers hovered on blurred wings over the water. We skipped nearly two centuries back in time, while Oom René read to us from various historical research papers he had collected. Much of the material came from a document called

A History of the Stephan Family of the Western Cape

, researched and written by iconic travel historian Eric Rosenthal back in 1955.

The Stephan family, originally from Germany, arrived in South Africa in the latter part of the 18

th

century and soon began trading with the farmers of the desolate West Coast. In exchange for grain and fish, they shipped in all manner of supplies for the isolated farming community. The ocean off the West Coast was a treasury of sea life. In those days, penguin eggs were ‘three bob to the hundred’ and lobster were abundant and used only for bait and feeding the poor. Penguin eggs, you’ll remember, were also the weapons of choice among battling guano hunters of the day.

How tastes had changed. Today, penguin tourism was more lucrative than penguin cuisine. But a lobster was another story, with some upmarket restaurants charging you R200 a tail or more.

René, whose father was also a sea captain in these parts, had been compiling research on the enterprising Stephans. He uncovered some poignant events, which began with the suicide of Captain Johan Daniel Stephan up at Hondeklip Bay.