Shorelines (19 page)

Authors: Chris Marais

Tags: #Shorelines: A Journey along the South African Coast

Like the cigarette baron who makes his millions from tobacco sales and devotes the rest of his life to the wellbeing of humanity, or the hunter who becomes the conservator, this poacher wanted to become a protector.

“The authorities can’t stop us poaching,” he said darkly. “Only we can stop it …”

Wilfred Chivell’s place lay just off Poacher’s Road on the way to Danger Point lighthouse. Wilfred – one of the foremost environmental champions along the Cape south coast and owner of Dyer Island Cruises – had offered to host us for a couple of nights as we picked away at the intricate matrix of Gans Bay life.

After our visit to the lighthouse, we returned to find Wilfred’s friend Susan Visagie hard at work in the kitchen on a magic meal involving spiced chicken, cheese toppings, vegetables and something outrageous in caramel toffee. Susan, who was also helping Wilfred plan his new eco-centre in Klein Bay, began laying out a dish containing four thawing pilchards, which I thought was a bit over the top for supper.

“No, that’s for the penguins,” she laughed, and took us outside to where two rather oily and depressed-looking African penguins lurked in a little enclosure. Nearby was a clutch of baby mountain tortoises and, in an igloo-shaped building, a series of swallows’ nests. Wilfred was a sucker for all kinds of strays, even writers bouncing up and down the coast.

“One of my jobs around here is to keep a constant supply of wet clay available for the swallows,” said the inventive Susan.

That night, around the dinner table, Wilfred told us what life had been like around here two years before.

“This town was a free-for-all. The police were escorting the poachers around. Yes, the poachers actually hired police to bring their armoured trucks to load up the perlemoen and take them through the road blocks.

“A friend of mine once came around a corner and saw a few dozen men from Blompark (the local ‘coloured’ village) in wet suits, about to dive into the sea. Then a Casspir drove up and he saw the policeman talk to the divers. The Casspir was then parked out of sight, in the bushes. The divers all went into the water, like a pack of seals. They later brought out their load of perlemoen and it was all loaded into the Casspir.

“I heard afterwards they had negotiated a R30-a-kilo handling fee with the police. So, let’s say they took out a tonne of perlemoen that day – that’s a R30 000 bribe for two policemen who earn maybe a couple of grand a month.

“I don’t blame the guys from Blompark. They see the poachers from Hawston and Hermanus come here for perlemoen because there’s nothing left over there. The local community once believed the government would protect them, but it didn’t. We need a community quota. Locals should benefit from their own resources.”

Wilfred’s young son, Dicky, later told us many schoolkids in Gans Bay were part-time students and full-time perlemoen poachers earning R250 a kilo.

“My dream is to change that around here,” Wilfred said with passion. “The younger generation have grown up with no respect for the sea because of the poaching. I’m putting up a marine centre to teach the kids of the Overstrand, from Betty’s Bay to Pearly Beach, about this.

“I never used to associate Gans Bay with perlemoen poaching and drugs. I thought we were different from Hermanus. But I mean, suddenly there’s R1 million on offer. How else can you make that kind of money so fast? Then you’re breaking the law anyway and you look at other ways of making money, like drug dealing. Then you need to keep it all safe so you get guns.”

The next day Wilfred took us to the perlemoen farm near the lighthouse, where I discovered that a perlemoen actually lives and breathes, a bit like you and me. I had a tug-of-war with a young perlemoen. We fought over a small piece of kelp and he won. I have to say I was nearly asleep at the time, having downed a couple of anti-seasickness tablets that morning before our outing with Dyer Island Cruises, followed by a brace of delicious beers for lunch. Alcohol and no-heave medication bring on drowsiness far more thoroughly than two hours of chamber music.

Nick Loubser, manager of the I&J perlemoen farm, took us to see his breeding stock. I became hypnotised by the stately movements of a perlemoen and its tiny eyes.

“These guys are tame,” he said. “They get used to people. Here, try feeding one.” And so I – in that dream world between sleep and wakefulness – tussled with a rather muscular perlemoen. Lillian, Wilfred’s sister, who worked in the packing section, said she was glad the perlemoen were exported live from the farm.

“I’ve become very fond of all of them,” she said. “I would hate to actually see them killed.” That’s a lot of personality for a glorified ashtray, I thought.

Perlemoen farming is pretty clean. They don’t produce protein-enriched waste, like fish do. They eat kelp, carefully harvested by local concessionaires so as not to destroy the beds. Hundreds of tonnes of these perlemoen are legally shipped off to the Far East in a kind of semi-hibernation state, which lasts for 42 hours.

This appeared to be the optimal future for the perlemoen industry of the southern Cape coast.

We liked John Moses’s ideas of local communities benefiting from perlemoen farms and trying to re-seed their coastal beds. Then the perlemoen business would have completely ‘clean hands’ and China could buy its wedding delicacies over the counter and the poachers and smugglers could all get legitimate jobs. And the drugs and the guns could all go away. And the lighthouse man would feel a lot better about working the night shift …

Gans Bay to Arniston

If you want a little peep into the deep history of this coast, go to the museum on the beach at Franskraal, east of Gans Bay. Jan ‘Pyp’ Fourie and his wife are the owner-curators and will show you some weird stuff from the brooding days of the guano hunters and the seal clubbers of Dyer Island. There’s a mattress full of genuine penguin down, embroidered Victorian underwear with cunning ‘toilet slits’ at the back, a carved wooden doll that used to belong to the daughter of a lighthouse keeper and various remnants from the wreck of

The Bulwark

, which went down on the rocks here in 1963.

“Part of the cargo was barrels of sweet wine,” Jan will tell you. “The men who first found the barrels got rip-roaring drunk. Then their wives marched down to the beach to give them hell, had a taste of the wine and fell about on the sand. In fact, the whole of Gans Bay – except for the pastor – was drunk for a week.”

In his lyrical, self-published book,

Dawn at Dyer

, Jan remembers:

“Aunty Maria … comes shuffling along and invites the visitors into the cottage. The kitchen smells of the morning’s fermenting yeast dough, this afternoon’s burnt milk and tonight’s paraffin for the Primus stove. A seafood concoction is simmering on the Bolinder stove. Yesterday’s unidentifiable stew lies in Foxie’s aluminium bowl under the green Oregon table. Aunty Maria lights her seventh Flag cigarette with the sixth one and pours strong ground coffee from the brightly scoured UGGI (Union Government Guano Islands) kettle. Later Edwin (her husband) serves sweet wine out of a small wicker bottle and then (much later) removes the gold needles out of the pot-bellied Gallotone tin, screws one into the gramophone’s head and winds the gramophone up and puts on a Columbia record.”

We told Jan that we’d just been with Wilfred Chivell for a few days, working on the ‘creature feature’ issues along the coast, which included sharks, whales, penguins and perlemoen.

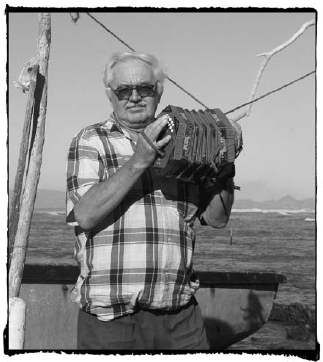

“Ah perlemoen,” he mused, while playing a wistful number on the accordion for us as we sat outside. “My Aunty Maria used to say you don’t just tenderise perlemoen slightly, you beat it within an inch of its life without damaging it. And then you fry it in a hot cast-iron pan. And then you eat it, just like that.”

His wife, ‘SD’, was equally fascinating. She took visitors on ghost tours of the district. She immediately pulled Jules aside and began talking of hitchhiker ghosts, “fish

smouse

from Napier” and a long-dead woman who sometimes danced in the night with her bridal veil blowing in the wind.

I, on the other hand, learnt from Jan that the seal clubbers used to dress in old, loose clothes because sometimes the seals would fight back and try to drag a careless clubber down to the water.

“And then it was useful to be wearing cheap clothes that could be easily torn off your body,” he said.

He played a few more tunes on the accordion, while I sat outside in the sun watching the sea, sipping some of Jan’s

witblits

. It was a good way to spend a Saturday morning and I said so.

“

Dit skiet jou kop oop

,” said Jan. Yup. It does seem to blast one’s head open.

By mid-morning Jules and I were filling up with diesel at the BP station in Gans Bay. I was trying to regain focus, and doing quite well, as long as I remained firmly shielded behind dark glasses. Jules had found a tick nestling in the crook between her little toe and the next one up the line. She sat back and sighed, waiting for the instant onset of tick-bite fever.

“I feel quite flushed,” she insisted.

“It’s the

witblits

,” I replied. But my thoughts were really on the Big Game of the day – the 2005 Currie Cup Rugby Final between the Free State Cheetahs and the Northern Transvaal Blue Bulls. The Bulls were favourites, but I fancied the fleet-footed fellows from the Free State. Were we going to get a chance to watch the game somewhere?

I heard someone singing a dreadful version of Willie Nelson’s classic, ‘Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain’, two doors down at a karaoke bar. And you know that song. Like perlemoen cooking, it’s really bad if it’s not performed properly.

“It’s gonna be ‘Blue Bulls Crying in the Rain’,” I told the petrol attendant, who couldn’t give a shit because he was more of a soccer fan.

A rather battered, sunburnt woman approached and said she was from Port Elizabeth but was living in Gans Bay because some very kind people had given her a little room to stay in with her children and she wasn’t asking for money but could we please go to the Spar supermarket with her and buy a loaf of bread and a can of pilchards so she could feed the kids?

“What?” I said, because I was in a

witblits

cave and had not followed a single word of that. She was just about to start the pitch again, when a local woman who could stand it no more appeared out of nowhere and shoved half a loaf of sliced brown bread and a can of (yes) pilchards in her hands.

Our beggar-lady was now in the awful position of trying to cadge cash for food while actually holding food. But we gave her some money anyway and she made for the karaoke bar.

Our mission for the morning was to purchase a scurrilous CD we’d heard about, produced in praise of perlemoen poachers by members of the locally famous Baardskeerdersbosorkes (Beard Shaving Bush Orchestra). Don’t try saying that with food in your mouth. And it’s not (as I’d originally assumed) a village bedecked with barber’s poles. It is named in honour of a large, hairy bug that reputedly likes to snip away at your whiskers while you sleep.

We traversed the dry, fawn fields of the Agulhas plain until we arrived at the settlement of Baardskeerdersbos. Two very old ladies told us where we could find Oom Manie Groenewald’s shop.

“But it’s closed,” they said in unison, looking startled when we jumped back into the

bakkie

. They called out:

“He lives right next door. We’ll call him for you.”

They took us to the front door and told us to knock. They bustled around the corner to the back of the house. An old fellow with white hair opened the door and peered out, like Badger disturbed in his Wild Wood lair.

“Yes?”

“Oh hi. We heard you’re selling a CD about perlemoen poachers.”

“Are you over 18?” this directed at me.

“Well, I’m not. But my wife is,” I said, still hiding behind my shades. And it wasn’t even that bright out.

“OK. Come in.” This was what I imagined a Saturday-afternoon drug deal in the

platteland

would feel like.

Inside, people sat around a table in the gloom of the kitchen, drinking brandy doubles with spring water and wasting no time about it. They were getting ready for The Big Game. Their hearts were also with the Cheetahs, but their money would be with the Blue Bulls.

“Have faith,” I assured them. “The Free State will triumph.” And who was this asshole from Jo’burg who comes in here and sits down with his dark glasses on and suddenly he’s a rugby expert? I could read the bubble. Let’s get him really drunk on

witblits

. Maybe he’ll turn out all right. They began to feed me large tots of white lightning, and out here in Baardskeerdersbos they seemed to drink only the finest of liquors. It all went down like golden tequila on an afternoon by the Sea of Cortez. With a “

haai op die aas

” (shark on the bait), as André Hartman would so famously say.

Oom Manie emerged from a back room with a silver briefcase, looking suitably ominous. I fingered the cash in my pocket and glanced over at the front door. Was it locked? If this deal went sour, Jules and I needed a quick exit. Where were the bloody car keys?