Shorelines (16 page)

Authors: Chris Marais

Tags: #Shorelines: A Journey along the South African Coast

We joined some of the locals at

Barbeyond

, a watering-hole and restaurant where the conversation drifted to people for whom status symbols, designer clothes, décor and expensive cars were important.

“We used to be those people,” said Nicola Lloyd, an estate agent. “We’ve seen it, done it and it doesn’t impress us any more. How many chairs can you sit on? It’s the quality and genuineness of the people out here that really attracted me.”

Great sentiments. But it still failed to explain why she and her mates were all waltzing around in Day Glo plastic clogs that came in a selection of “slurpy colours”, from lime green to fire-engine red to Barbie pink.

“Oh,” she laughed. “These are Crocs. They’ve got good grip, never slip, massage the feet and can be rinsed off after walking in the sea. People who spend a lot of time on their feet, like chefs and waiters, swear by them. They are so comfortable, once you’ve tried them, you’ll be hooked.”

Perhaps the real reason everyone wore lurid, laid-back shoes in Pringle Bay lies with the local legend that many of the long-time residents were fond of a cocktail of gin steeped in marijuana – to be drunk behind closed doors every morning. Which was definitely

one

way of dealing with the baboon problem …

Walker Bay

“My hand with der cold is so blue,

Der weather it ain’t so hot too,

Der wind she just blow, and der snow she just snow

Ikke hval, ikke hval, ikke hval

(No whales, no whales, no whales).

Der gunners have fell in der drink,

Der guns just shoot bullshit I think,

Dey spin us a line, dis would be a gold mine,

Ikke hval, ikke hval, ikke hval.”

‘Ballad of the Frustrated Whaler’ by Gordon Keen, as quoted in

To Catch a Whale

by Terence Wise.

I once found the work of Terence Wise in a little bookshop somewhere in the Karoo. Although I’d never been to sea in a factory ship all a-slip with whale gore and blubber and steaming guts, Terence’s tome took me right into the belly of the beast – so to speak.

It’s one of those old-school books that glorify life at sea with good mates and a ‘manly job’, complete with anecdotes of alcohol and hookers during shore leave, not to mention the mandatory first-meal-ashore of steak, eggs and chips. In among giant pots of boiling whale oil, rotting meat and quivering blubber (with a gaunt, hard-faced Captain Ahab-type skipper looking down on it all), the crew stumbled and hacked and sliced and made its bloody way over the deck. They were generally underpaid, overworked and ‘sold a crock’ on the wonders of foreign ports and dusky maidens.

We spoke to Irene Toerien, a lecturer on whales.

“Killing whales seemed to have affected the personalities of whalers,” she said. “They were often morose and miserable people, and they only came alive once they leapt up onto a dead whale. They could hardly wait to sink in the flensing knife and the cutting spade.

“I once spoke to an old whaler who lived in Bergvliet, Cape Town. He had worked on the

Willem Barendsz

, quite a famous whaling ship. He said he wasn’t proud of what he had done. He told me what it was like, shooting the whale gun. They had to get a grenade into the whale so that it swivelled its three prongs and churned up the flesh. Sometimes one shot wasn’t enough.”

Irene lived in Hermanus, now marketed as the Whale Capital of the World. She saw her first whale at the age of 13 in 1953 and the sight transfixed her. She didn’t see one for another five years. Nowadays, in the season, hardly a day goes by without a whale sighting. Use some imagination as you look out to sea, and it could almost feel like 1 000 years ago.

Life was OK in the world of whales back in the days when what passes for civilisation was a pup. When

Strandlopers

walked our shores, they used to feed, in a totally sustainable manner, on the blubber of beached whales. Across the oceans to the north, Inuits and other Arctic tribes hunted whales from boats without ever seriously denting their numbers. Off the southern coast of Madagascar, tribes of African origin went out to sea, jumped on passing whales and “hammered a wooden plug into the blow hole”, says Wise.

This, in hunting parlance, makes the southern Madagascan possibly the bravest whaler of all time – and gives the animal a real fighting chance.

The Basques of Europe got in on the act in the 11

th

century and set up a full-on whaling industry. They lanced the whale’s lungs so that it drowned in its own blood. Then they taught their skills to the Dutch and the English, and suddenly you didn’t want to be a whale in northern waters.

Whale products – over the centuries – have been many and varied. The flexible baleen was used for umbrella and bicycle-wheel spokes, buggy whips, shoe horns, chair springs, corset boning, hairbrush bristles, fans … even the fine baleen hairs were used for brooms. The Russians specialised in the production of golf bags fashioned from whale penises.

Spermacetti, found in the heads of sperm whales, was used to create nitroglycerine (an essential item in certain explosives), blubber went into candles, and whale oil lubricated engines and turned up in cosmetics, margarine and soap. It was the petrochemical industry of its day and also a food additive. As a child, I once heard that there was whale in my ice cream. I went on an ‘ice cream hunger strike’ for at least three weeks before being seduced back to the Walls cart by the siren song of the dreaded Eskimo Pie.

Along the coastline of South Africa, whales were big business. In the early days of colonisation, Jan van Riebeeck came across a dead whale on the beach near Salt River mouth. He jumped on top of it, struck a heroic pose and called upon his trumpeter to play ‘Wilhelmus van Nassauwen’, no doubt a stirring martial number.

Between 1785 and 1805, more than 12 000 southern right whales died along the southern coastline of South Africa. Whalers came from all over the world to join in the slaughter. In the early 1800s, whaling was right up there with wine and agriculture as one of the three most lucrative industries around here.

By the middle of the 19

th

century, southern right numbers were a tiny fraction of what they had been. But the whaling continued all around the world, and the biggest victims were the enormous blue whales. Even today, after decades of moratoria and restrictions on whaling, their numbers are so depleted that some experts believe they cannot hear each other in the sea any more. As a result, they cannot mate easily.

The Japanese kicked off their whaling industry by using poison on whales. By the 1300s they switched to the spear, which involved an attack at close quarters. It turned into a stylised ritual. Wise points out something interesting: both the Shinto and Buddhist religions forbade the eating of meat. Whales were thought to be fish. Now that everyone knows whales are mammals, the irony of it all is that whale meat should be more of a taboo in Japan than almost anywhere else on earth.

According to reports in 2005, the desire in Japan for whale meat started to flag. The local industry (which still killed whales for ‘scientific purposes’) was concerned about its massive stocks of frozen whale meat lying in storage while the youth of Japan wolfed down their McMeals instead. The

Washington Post

reported that Japanese students were targeted in a marketing campaign to get them to eat more whale. They were fed plates of deep-fried whale chunks at school and given recipes for whale burgers.

Opinion polls, however, suggested that Japanese kids were more interested in saving whales than eating them. Tokyo restaurants had started offering ‘early bird’ specials on whale meals at a big discount. This did not sit well with the Japanese government, who said the nation needed whale meat to become more self-sufficient. They were specifically referring to Minke whales, which, they claimed, had eaten up most of their local stocks of cod and sardines.

Although Japan has been eating whale for centuries, it was their post-World War II food shortage that propelled them into destroying global stocks. They were, in fact, encouraged by the American military to go out and kill whales for dinner. The American Occupation overlord, General Douglas MacArthur, said whales were “cheap protein” and the Japanese should tuck in with gusto.

The wheel turned, and now the American anti-whaling lobby was hoping that Japan’s growing love of fast food would stave off attempts to revive serious whale cuisine.

Another alarming factor for those who liked blubber burgers and flesh of Minke was that a lot of it, by the beginning of the 21

st

century, was contaminated with mercury. Chemical analysis of 60 samples of meat and blubber bought over the counter from Japanese supermarkets revealed dangerous levels of mercury. “Whales, dolphins and porpoises (cetaceans) are susceptible to accumulating toxins like mercury, as they are long-lived and feed at high trophic levels,” stated a report handed in at the 55

th

AGM of the International Whaling Commission. “Mercury is a potent neurotoxin, and scientists have found that even low concentrations can cause damage to nervous systems. Developing foetuses and children are especially at risk.”

The science-fiction writer Arthur C Clarke once predicted that the world would ‘farm’ cetaceans in ocean corrals, in much the same way that we farm beef. Imagine feed lots for dolphins, I thought. But then, good fortune, good sense and inventiveness all converged to give the whales of the world a break. It was called whale tourism – the greatest threat to whaling ever.

As far back as 1997 Jules and I had been out to sea with a posse of teenage Japanese tourists to look for whales off the coast of Plettenberg Bay. We saw their faces as plumes of whale breath were spotted just after the morning sun rose over the Indian Ocean. Their joy as we found ourselves in the midst of more than 4 000 cavorting common dolphins and then later a brace of southern right whales was, to quote a classic poet, “unconfined”. Not one of the Japanese kids said they felt peckish.

For some reason, whales and humans have an emotional link. We have it with elephants as well. In times gone by, humans misread that link and presumed it meant we had to hunt them down, butcher them and then think of them with great nostalgia in the evenings as we looked upon their carved bones.

“I could just love you to death.” And we actually meant it.

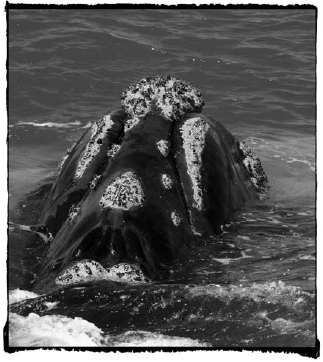

Nowadays, it is one of life’s finer pleasures to sit on the rocks in Walker Bay, with the tourist buzz of Hermanus behind us, and quietly observe the great pods of southern right whales coming in to show off new babies and generally rest up from their hectic Antarctic krill-feasts. As the people – many of them Japanese visitors – watched the whales in the late-afternoon light, a festival of quiet, exultant joy spread over all of us like magical fairy dust. I’m a hoary old hack who’s seen it all. Give me a good dose of satire over a sunset any day. And yet, whenever Jules and I find ourselves on the ‘whale rocks’ of Hermanus, we buy into the rapture of seeing a southern right.

Just below us was Bientang’s Cave, a restaurant named after the last-known

Strandloper

in the area. She lived in a nearby cave in the late 1700s and, by all accounts, made a very comfortable nest for herself. She drank water from a mountain stream, gathered seafood (like someone you’re going to meet later in this chronicle – South Africa’s only real Robinson Crusoe, still going strong in 2005) and cultivated a little vegetable garden for herself.

Bientang was said to communicate with all manner of animals, including the southern right whales. And the legend goes that year after year the whales would return to this spot in Walker Bay to speak with her. Perhaps to give her an update on matters down south, where the emperor penguins hung out. It was a good legend that fitted in perfectly with the business of watching whales – the southern rights in particular.

This species of whale was enjoying an amazing comeback from the brink of extinction. As we embarked on our

Shorelines

venture, there were more southern right whales off our Cape coast than in the previous 150 years. By 2005, about 2 000 were visiting our shores each year, and their numbers were doubling every decade. The whales – originally called ‘right’ whales because they were the ‘right’ whales to hunt – were down to a tiny group of 40 adult females by 1940, when it was finally decided that they were to be protected. There used to be nearly 300 000 of them before intensive whaling began in the 18

th

century – and they were now up to total of about 12 000, thinly spread across the southern hemisphere’s oceans.

As I write this in the South African autumn of 2006, the whale-watching industry is growing by 40% a year and is a worldwide business worth US$1 billion. No small potatoes, even for the lobbyists in the ‘If It Pays, It Stays’ camp of conservation. It’s like the whales said:

“Don’t shoot us. We’ll come and visit you. Make you happy. Make you rich.”

Land-based whale watching is becoming so popular in South Africa that it is bringing more tourists here than the legendary Kruger National Park, which offers the Big Five of the animal kingdom. And where the whales go, the merchandising is not far behind. Hermanus is awash with whale themes, whale ‘stuff’ and very good whale art. A whale festival, a nearby estate that offers a superb Southern Right brand of wines and a string of guesthouses and restaurants flying whale logos – the sleepy little town of Hermanus has woken up and become Whale Central to the world.