Radio Free Boston (11 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

“A lot of what she played are the songs you hear on Classic Rock radio today,” added Tommy Hadges. Maxanne would eventually be credited with championing Boston groups like the J. Geils Band, Aerosmith, and the Cars, and counted some less famous bands from the area as favorites, including Reddy Teddy, Nervous Eaters, Fox Pass, and Willie “Loco” Alexander.

Hadges continued, “She was the one that was really able to find the cuts that seemed to resonate with the audience.” In regard to “resonating,” Maxanne also liked to

feel

the music she played. “She ran those speakers at the loudest possible level imaginable,” Hadges joked seriously. “The production room at Stuart Street was right next to the air studio; Andy Beaubien and I would try to get some work [done] in the afternoon. But sometimes it was difficult because Maxanne had her speakers up so loud that the whole place was rattling!”

With its latest lineup in place, the on-air collective headed into 1971 as darlings of the underground media, standard-bearers for the counterculture bohemia entrenched in Boston, and heroes to so many young bands. Artists were offered free reign to drop in at Stuart Street for interviews and to play live on the air. “I remember one of the first live broadcasts was Jesse Colin Young and the Youngbloods,” Kate Curran recalled. “They set them up front in the sales office and they played for an hour or two. Dr. John came in and all the volunteers and hangers-on were there in the Listener Line area going, âWow, it's Dr. John!' On his way out he looked at us and said, âCatch you in the moonbeams.' It was soooo Dr. John!” Others as diverse as Hound Dog Taylor, Van Morrison, Pete Townshend, and Gary Burton also dropped in. One historic evening in November 1970, Laquidara hosted an acoustic guitar summit on his show featuring Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, and Duane Allman (who had less than a year to live).

To further the egalitarian goals of a hippie “revolution,” yet still bring in the cash needed to keep business going, the staff needed to confront and compromise with the typical business model that made any radio station's survival possible. The most radical viewpoint was to not sell advertising at all, like college radio stations. But where would the money come from with no school or foundation underwriting the programming? The

WBCN

compromise was to place a certain limit on the number of commercials allowed on the air, a practice begun by Ray Riepen and agreed to by the staff. “One of the initial deals was eight ads an hour,” the general manager said. Because demand usually outpaced inventory for the first twenty-four months after the change from classical music, this choice worked for the station.

Boston

magazine reported that as of May 1970, the rate charged for a one-time, one-minute commercial in

AAA

time (the most coveted positions in the evening) on

WBCN

was $32, and the net sales for that March “rose to the highest in the station's history, surpassing all other

FM

stations in the city.” The 20 May 1970 edition of the

New York Times

, in a story entitled “Around Country,

FM

Turns to Rock,” pictured Laquidara working in the studio and pointed out that

WBCN'S

shift from classical to rock had “enriched the station by $41,000 a month.”

The

WBCN

collective considered the style and presentation of the commercials to be equally important to the number. Some accounts, like any of the U.S. Armed Services or the tobacco companies, were flat-out refused. Other national companies that might be welcomed were asked to leave their slick and professional, agency-produced commercials at the door, and ads with jingles in them were also turned down. A potential advertiser had to agree that its spots could be rewritten, produced, and voiced by '

BCN

announcers, an attempt to adapt the messages to echo the “underground” attitude at the station and create palatable, even entertaining, vignettes for its listeners. Tim Montgomery, who replaced Debbie Ullman in sales in 1971, recalled, “Up until 1973, maybe '74, we didn't run any prerecorded commercials. It didn't matter who the advertiser was; they were all either [done] live or we produced them.” With his rate cards and station information stored, ironically, in an old army surplus gas mask bag, Montgomery canvassed local businesses looking for advertisers. Then, “I'd sell the ad, convince them that

WBCN

was the right kind of radio, but then I had the task of saying, âWell, you might have a lovely spot, but we can't run it. [But], believe me, we know how to talk to our listeners.'” Montgomery quickly became one of '

BCN'S

most successful rising stars. “I must have written thousands of ads in the time I was there. Then I had to voice and produce them myself. I had no experience doing that; I just picked it up.” Montgomery became “the voice” for Underground Camera, a major supporter of the early

WBCN

. “They were ahead of their time, in thinking that you should use a regular person to voice the ads. Of course, everybody on '

BCN

was an ordinary person, I suppose, in their delivery and voice. There were no actors behind the mike at

WBCN

.” Laughing, he added, “Except for Charles!”

Constant debate over which commercials would be acceptable to

WBCN'S

hip, young audience led to disagreements between the staff and Ray Riepen, who turned bitter remembering that aspect of his '

BCN

stewardship. “I got screwed a few times because they, literally, turned down [accounts] instead of taking them and telling them what to do [to conform with '

BCN'S

image]. Kinney Shoes and the big companies were calling me; Coca-Cola called up, and the guys in the sales room would not take them.”

“No one wanted Coca-Cola on

WBCN

because it epitomized âThe Man,'” Tim Montgomery stated. Nevertheless, some in sales felt that, with the proper tweaking, the soft drink giant's message might be acceptable. Some sample Coca-Cola commercials were mailed up from the ad agency in New York so the

DJS

might find some creative ways to rework the content. In the meantime, Tim Montgomery, as the new sales manager, headed to Manhattan as part of his first national sales call. “My first time in New York; I was probably all of twenty-five years old and a little green. My [national sales] rep and I went to McCann-Erickson, which was the agency for Coca-Cola.” The powerful advertising firm had been a key player in developing “I'd Love to Teach the World to Sing (In Perfect Harmony)” into a massive 1972 Coke marketing campaign. But that jingle, also a best-selling Top 10 hit in America, clashed hideously with '

BCN'S

radical musical views and countercultural slant, and should have portended the debacle to come.

Montgomery headed into his big meeting with McCann's media buyer. “I introduced myself. She was a fairly burly woman behind her desk. She stood up, looked me in the eye, and said, âWho the fuck do you think you are!' I was, sort of, blown back into my chair; I'm going, âUh . . . Uh . . .' This was my greeting, my first call!” Montgomery sat there stunned. The customary civility and decorum associated with any high-level business negotiation had been rudely tossed out the windowâand flown back in his face. He was totally mystified as to why. The woman held up a small cardboard box for Montgomery to see; it was one of the mailers that agencies used to ship reel-to-reel tapes of commercials. This particular box looked like it had been mailed to

WBCN

and then returned. “I looked at it and I saw that someone had written in grease pencil on it, â

FUCK

YOU

!' Whoever was in production at the time, I think it might have been Sam, got the tape at the station and mailed it back like that! Suffice it to say, it was a long time before we got any Coca-Cola ads!” When asked about his possible role in the matter, Sam Kopper only smiled deviously and pled ignorance.

The inmates ran the asylum, but Riepen didn't want to believe it. Debate over the commercials extended into the programming. As

WBCN

had been set up to be a true free-form music vehicle, these disagreements were seen by the staff as sacrilegious. A famous story in this regard began with a normal Sunday midday show hosted by John Brodey, who had only recently conquered the stage fright he'd had on his initial shows. “I couldn't speak; my voice just froze. I'd just play musicâfor hours.” Brodey was finally getting

his rhythm, and as Charles Laquidara put it in an essay he wrote in 1978, “Sunday radio was a snap: just throw on a little Joni Mitchell, and if you need to organize, put on a side or two of

Woodstock

.” Laquidara would probably need some of that organizational time since he was relieving Brodey at five and had spent the entire day tripping on acid: “Riding the cat, falling in the park, sitting paranoid in the shade, listening to âLet It Be' and âBridge Over Troubled Water' on the stereo, drawing pictures, philosophizing, and finding easy solutions to problems that had stumped the world's greatest minds.” Still buzzing, Laquidara drove in while listening to the station. “Good old John Brodey was playing the Ginger Baker cut from the Blind Faith album. Thump-thump tha-thump. âWhat a mothafuckin' drummer!' I thought.”

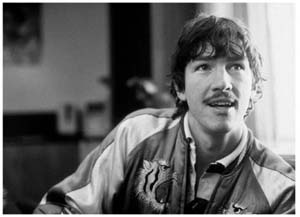

John Brodey, digging a Ginger Baker drum solo. Photo by Dan Beach.

“You could play anything, and I took that pretty literally,” recalled Brodey, who isn't sure exactly what he was playing that day: “I think it was âToad' because the live version does have a twelve-minute drum solo.” So, there's a discrepancy about whether the cut was “Do What You Like” by Blind Faith or “Toad” from Cream. Which one it was is not necessarily important, since both featured English drummer Ginger Baker performing one of his trademark solos for a very

long

time.

“The red phone in the studio blinks; it's the hotline . . . somebody important,” Brodey recalled. “It was Ray, who immediately says, âWhat the fuck are you doing?' I'm like, âOh my God, it's the big guy!' He said, âWhat in the hell made you think that playing a ninety-minute drum solo on a Sunday afternoon was a good idea?' I said, âWell, I . . .' Then he said, âShut up!' And then something along the lines of, âThat's going to be your last drum solo!' I thought, âThat's it, I'm done.'” Riepen admitted, “I never called [the jocks on the air], but I did that day. I said, âHey pal, that's a tune-out! You can't play a drum solo for twenty-two minutes regardless of what kind of station we've got!'” By the time Laquidara walked into the studio “Brodey looked pale. He was visibly shaken. He explained that the station president had just called him on the hotline and blasted him for playing a long drum solo.” Laquidara was outraged at Riepen's action, which in his view violated one of

WBCN'S

fundamental constructs. “ âOh John, I'm sorry, he's not supposed to do that. He should know better.' John went home totally deflated and there I was, all alone in that studio, my head still spinning from breakfast”â

LSD

breakfast, no less.

Some strange and uniquely personal gears clicked in Laquidara's mind at that point, setting him on a course that most would not have taken. From his 1978 essay, he said, “I put the long version of âToad' on the turntable and turned on the mike. âGood afternoon. This is

WBCN

in Boston. My name is Charles Laquidara. We have this boss who thinks he has impeccable taste, and he sometimes likes to impress his friends so he calls up the announcers on the hotline and makes requests or gives orders, or yells at us. It's hard to do a good show after the boss calls, and poor John Brodey, the guy who was just on before me, got this call from our boss and was yelled at because he played a drum solo. I guess we should settle this once and for all.'” Laquidara admitted being plagued by self-doubt as his inner voice of reason fought for control: “God, Charles, wait! What the fuck are you saying? People out there must think you're crazy.” Nevertheless, outrage at Riepen, who had now become “the Man,” and definitely some residual chemical agents, prompted Laquidara to ignore his unease and push the turntable switch. Ginger Baker took off on his extended rhythmic romp; and that was just the beginning. The

DJ

rooted through the vast

WBCN

library and came up next with “Mutiny,” a seven-and-a-half-minute drum piece from the Aynsley Dunbar Retaliation, following that with some classic jazz thumping from Buddy Rich. “When they found me two hours later,

I was wrapped around a beanbag chair in a corner of the air studio. Side 4 of

Tommy

was just ending. âIt's okay, Charles. Man, that was beautiful. The whole town's talking about it. You're a hero!'” But he was certain he'd be fired, as he wrote in his essay: “A hero? An unemployed hero. A hero on welfare. You-got-any-spare-change-mister hero. I can't even work at the

Phoenix

. The son-of-a-bitch owns that too!”