Radio Free Boston (9 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

Bo Burlingham was now a happy man. He had a position that suited his interests, at a radio station whose employees were clearly not conservative or even mainstream in their political leanings. “I started on a Monday as news director. We would take news stories and insert sound and music segments. I was so slow at it at first that we had a slogan for it: âYesterday's storiesâtomorrow!' Tuesday we had improved and by Wednesday we were just hitting our stride. Then on Thursday, the teletype went off. I went over to check the machine and noticed the first word said â

BULLETIN

.' So, this had to be important, but you had to wait while it typed out each line.” As Burlingham read the words clacking out on the machine below, his body began to chill. “The title was something like, âFEDERAL GRAND JURY IN DETROIT INDICTS 13 MEMBERS OF THE RADICAL GROUP, THE WEATHERMEN, ON CHARGES OF CONSPIRACY.' All the first names were people from the leadership, people I knew, some of whom were underground by this point. Then the teletype gets to the last name and I saw that it was . . . me! I just reached down, ripped off the story, folded it and put it in my pocket.” Numbly, Burlingham walked into the next room, bumped into Laquidara, and handed him the incriminating evidence, but he didn't get a whole lot of sympathy at first: “He reads the story and the first thing he's worried about is where they're going to get a new news director! I don't know if it was him or someone else who said, âYou're going to need a lawyer.'”

Bo Burlingham confessed to his membership in the Weather Underground but asserted that he did not serve in any critical, policy-making role. “I was in and out very quickly. But, there had been a mole in the organization, a person whom I befriended and got to know. I guess I was indicted because they needed to enter in testimony from me at the trial.” Danny Schechter revealed, “It was part of an

FBI

effort [called] â

COINTELPRO

,' [an operation] to stop various protest movements in America by infiltrating them.” Burlingham contacted his buddy, Michael Ansara, who had been the head of the Harvard chapter of

SDS

and the one who had originally tipped him off about the '

BCN

job; then the two sped off to Cambridge on Ansara's motorcycle to break the news to Riepen. “We stopped in Kendall Square for something to eat and the story came on the television, naming all the names and showing pictures. I started to look down to try to hide my face; I could just picture my photo on the screen and someone across the room shouting, âThat's him!' But, [luckily] they didn't show a picture.” After telling Riepen about the dilemma, the mercurial manager's advice

was also, “Get a lawyer,” which Burlingham did immediately. “[The lawyer] asked me whether I was going to turn myself in or go into hiding. I said I'd turn myself in, so he arranged for me to do that at the courthouse. The judge posted bail at $100,000 with lots of conditions: I had to surrender my passport, had to check in [regularly], advise them of any travel plans, and I couldn't drive through Rhode Island for some reason!”

While Bo Burlingham waited for a trial, which wouldn't begin for three more years, Riepen tried to figure out what to do with the alleged co-conspirator. The often-antagonistic comments about the government spoken on the air at

WBCN

didn't necessarily endear the station with local and federal authorities, plus Riepen believed that a couple of break-ins at his apartment were not just burglaries but the results of a government investigation into Boston's radical movement. “When [Burlingham] got indicted,” the general manager divulged, “I said, âI've got a federally licensed business here, and I've had enough heat from these guys.'”

“Ray decided that perhaps it would be best if I left '

BCN

,” Burlingham added.

“So, I gave him a job at my newspaper,” Riepen said. Earlier that year, the entrepreneur had amassed some of his earnings from the Boston Tea Party and

WBCN

, joined with a financial partner, and invested in a tiny rag called the

Cambridge Phoenix

. Infusing the publication with cash and beefing up the editorial and reporting staff, their goal was to make a serious run at becoming Boston's weekly of choice. In a noble gesture, Riepen steered Burlingham toward this new opportunity. “He hooked me up with Harper Barnes, his editor, and I wrote stories for the

Cambridge Phoenix

under my wife Lisa's name.”

When the trial of the Weather Underground leaders finally got to court in 1973, it was asserted that the government had obtained information about the defendants by wire taps and other potentially illegal surveillance. With the Supreme Court prohibiting electronic eavesdropping without first obtaining a court order, prosecutors realized they would be vulnerable in their efforts to win the case, since at least some of their critical information had been gathered by questionable means. Subsequently, the suit fell apart, and the charges were eventually dropped. Burlingham got his passport back and his name cleared, and then went on to flourish in a journalism career for many years to come. Despite his many successes, though, he'd never forget his four days working at

WBCN

in 1970.

In the sixties and early seventies, many policy makers in Washington considered the protest activities of its citizens as an outright attack on the country. With the Weathermen declaring an official state of war on the U.S. government in 1970, it was clear that the gloves had been completely taken off on both sides. Joe Rogers talked about the feeling of that time: “You know how you can be young and paranoid . . . but there was a sense that something politically important was going on and that you might very well be being watched. Who knew if the

FBI

would come storming through the door.” Andy Beaubien added, “This may seem naive now, but there was a group of us at [

WBCN

] who really believed we were on the verge of a political revolution in the U.S. and if you listen to an album like

Volunteers

by the Jefferson Airplane, it expressed the mood of the time. The station went through a very political stage around 1970, '71, '72. We were pretty far out on the left and a lot of what we were doing on the air had to do with the politics of the time . . . this was Vietnam and a little later it was Watergate.” In amazement, he recalled, “I remember emceeing a concert at

BU

; the artist was Buddy Miles. It was a white college audience and it was a benefit for the Black Panthers!”

Danny Schechter, the man chosen to replace Bo Burlingham, would be the asset that drove

WBCN

squarely into the political stream. By the time he arrived in Boston, he had already graduated from Cornell University and gotten his master's at the London School of Economics, but working in an environment that combined his pursuit of journalism and love of music seemed like the perfect place to be. At first, though, despite all of his schooling, and some journalism experience, Schechter began at the bottom as an intern working for his predecessor. “News at that time consisted of some headlines and one produced feature that Charles read and Bo wrote,” he remembered. “But people said that Bo didn't have any radio experience and was going to have to produce an expanded newscast. Did I want to help out? So I did it first on a volunteer basis because I was interested in radio news, which I knew nothing about. It was the blind leading the blind, in a way!” He had barely started learning the ropes before Burlingham's indictment and sudden exit elevated the young intern into the principal news position. “There was, at the time, an advertising campaign that said, âI got my job through the

New York Times

,' so I joked that, âI got my job at '

BCN

through the

FBI

!'”

It wasn't long before Schechter adopted the famous radio handle that

would remain with him throughout his career. “I was writing news [stories] for the

DJS

to read and I wasn't the best of typists, so I would correct the copy with a pen. [But] my penmanship was worse than my typing! At one point I handed Jim Parry some news which, typically, had my scrawl on it. He goes, âWhat's this? I can't read this!

You

read this and

I'm

going to take a leak.'” Parry got behind the microphone and gave Schechter an impromptu windup for his very first radio moment: “He said something like, âNow ladies and gentlemen, I'm going to introduce Danny Schechterâthe news detector . . . the news inspector . . . the

NEWS DISSECTOR

!!' At which point I read the news, kind of terrified . . . then ended up staying there for ten years. So, thanks to Jim Parry, I adopted this News Dissector brand, if you will, and used that as a way to differentiate what I was doing from what others were doing in Boston.”

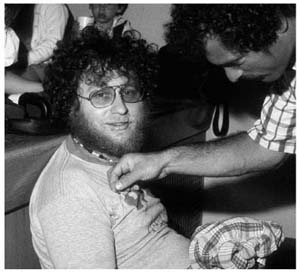

On a break from giving the news, Danny Schechter gives blood. Photo by Dan Beach.

The News Dissector lost his shakiness and grew in his craft.

We were playing to an audience in Boston, particularly three hundred thousand college students, at a time when the counterculture was in ascendancy and the antiwar movement was, in many ways, based in [the city] with Howard

Zinn, Noam Chomsky, and other intellectuals. This was something that was popular; in 1972, the whole country was a landslide for Richard Nixon, except for Massachusetts. We did a radio show then called “Nixon: 49, America: 1,” which was about that election. When most people think of politics they think of Democrats and Republicans and elected officials. That's not how we defined politics. We were really talking about politics in the community and on the streets . . . politics of protest and culture. '

BCN

was, sort of, charging in another direction. We weren't lecturing the audience; it was [more] like engaging the audience.

Danny Schechter began to build up a department that could handle the amount of story investigation and production time needed to create two regular news broadcasts at 6:00 p.m. and 10:00 p.m., plus his frequent special reports. Bill Lichtenstein, who started as a volunteer in 1970, recalled that

WBCN

excelled at in-depth coverage but eschewed the “on the hour” punctuality that characterized all of the other television or radio news reporters in the area. “The six o'clock [news] would go on the air sometime between 6:00 and 7:30, and could run anywhere from twenty-five minutes to an hour. The ten o'clock news would go on anytime between 10:05 [and] 11:00 and run from fifteen to forty-five minutes, depending on what was going on.” He added, with a laugh, “If Spiro Agnew was in town and there was a full-scale riot with people [being] arrested and we were getting phone calls from them, we'd be editing things together and Danny would be going into the studio with thirty-two carts [tape cartridges with recorded segments on them]. Charles would say, âWe've got a whole report coming up at 11:00, so stay tuned.' And

that

would be the ten o'clock news.”

Like Schechter and most of the

WBCN

air staff before him, Lichtenstein was thrown in the deep end suddenly. He arrived at the station as a fourteen-year-old junior high student from Newton, which had a curriculum requiring its students to go into the community and find a volunteer job. “I called '

BCN

and they had just started the Listener Line. The person I spoke to, Kate Curran, who[m] Charles brought in to set up this system to handle all the phone calls, swears that I said I was sixteen. So, I started answering the phone, in the days before the Internet and Google; [

WBCN

] prided themselves in the fact that you could find out anything! They stocked bookcases with reference books because people would call up with all kinds of questions . . . like âWhat's the population of Sri Lanka?'”

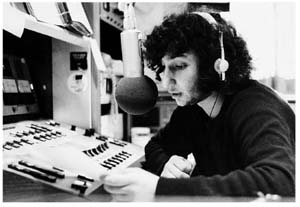

Bill Lichtenstein,

WBCN'S

youngest employee, covered a Black Panther story at age 14. Photo by Don Sanford.

One day, the fourteen-year-oldâahem, the

sixteen-year-old

âfell under the gaze of a stressed-out Schechter, as the volunteer worked one of his many Listener Line shifts.