Radio Free Boston (7 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

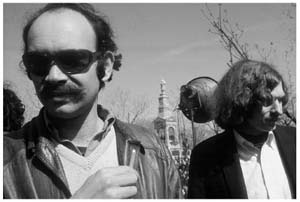

New recruits: J.J. Jackson and Charles Laquidara on Cambridge Common, 1969. Photo by Sam Kopper.

Laquidara found out about the opportunity from his buddy Dave Pierce, another starving graduate who wanted more than anything to be a rock and roll disc jockey. He had settled for spinning classical records on the local radio station

KPPC-FM

, owned by the Presbyterian church, which programmed the music when it wasn't broadcasting Sunday services or midweek devotionals. Pierce, who knew very little about the genre, nevertheless took the gig and would listen to his favorite R & B records off the air while he spun the long symphonic pieces on the radio. He invited Laquidara, who knew slightly more about classical music, down to the station to help him out. “Dave Pierce taught me how to do radio, how to run the board, and he got me a job,” Laquidara remembered. “I couldn't pronounce the names of the composers, so I had to be tutored.” While the two gradually got a handle on how to suavely pronounce Shostakovich and Prokofiev like the pros, they managed to survive at

KPPC

while their station went through some rocky management changes, passing from a classical format to jazz, and then finally morphing into the second underground rock station in the country in 1967.

A year later, now a rock radio veteran with experience under his belt, Charles Laquidara had to head east when his mother died. Back in Milford,

he tuned in

WBCN

, heard Jim Parry on the air, and called him up. When Parry noted Laquidara's local roots and West Coast experience, he encouraged him to visit the station, where the two met and Parry introduced him to fellow

KPPC-FM

alum Steve Segal. Now, as the '

BCN'S

overnight star was about to leave, Laquidara found himself in the perfect spot. Sam Kopper recounted: “I remember there was this [final] falling out between Peter Wolf and Ray. So, it went [quickly] from âmaybe we should bring this Laquidara dude in' to âLaquidara is doing nights.'”

“The timing was amazing,” Steve Segal mentioned. “Charles just walked in. I said, âSam and I just thought we'd throw you on the air and see what happens.' At the time, he was an actor playing an underground disc jockey, but over the years he became a knockout performer.”

“I was a mediocre everything: a writer, cartoonist, actor, disc jockey,” Laquidara explained. “However, in 1968, with the advent of underground radio, there was a place for a guy who was simply real. He didn't have to have a deep voice; he didn't have to talk fast or have a golden throat. And, he could fuck up, which I did . . . a lot! Sam Kopper went to Ray Riepen and he hired me. To this day I'm indebted to Ray Riepen.” Then he added with a snicker, “Even though he tried to fire me a couple times.”

The only thing anybody was ever concerned about was the

FCC

. That was the only brake on the system. Nobody would ever say, politically: “You're too radical.” Frankly, the listeners loved it, the bands loved it, the staff loved it.

BILL LICHTENSTEIN

I READ

THE NEWS

TODAY

By the beginning of 1969, the

Wheels of Fire

album by Cream, with its rambling, fifteen-minute rock jams and abstruse, poetic lyrics, had gone to number 1 in America; the “all-you-need-is-love” Beatles were squabbling, and Janis Joplin brought San Francisco acid blues to the top of the album chart. Martin Luther King Jr.'s path of nonviolent civil rights protest ended in gunfire and death; three Americans had just circled the moon in Apollo 8; the Vietnamese peace talks commenced in Paris; the Democratic National Convention had been ravaged by a torrent of street violence; and likely presidential nominee Bobby Kennedy had been assassinated in Los Angeles. “The jocks really knew their stuff,” Ron Della Chiesa observed. “They were on the edge of what was new, what was happening, and what the youth market was going to be. Think of the timing of all that: Vietnam was going on, the protests, civil rights, the spin-offs from the assassinations, the country in upheaval. Then, there was the music; it couldn't have been

more timely . . . the stars lined up.” Tommy Hadges remembered, “There was an amazing array of music that was coming out. The war was going on; there was a cultural revolution, a drug revolution, a political revolution. But [it was] also about being in Boston . . . in a city where it is renewed and refreshed every year with all the new students that come in. With the university environment having a lot to do with the social revolution going on,

WBCN

fit right into that.”

Joe Rogers offered his view of

WBCN'S

music mission: “I always felt that I was there to bring this music to the people. The reflex was, you've got this huge record library and âlook at the things I've found!' The emphasis was on doing sets [of music] and segues; we thought that's what our craft was. You tried to sneak one song into another in a clever way, whatever that would mean.”

“It was kind of like college radio, you played the music you liked and you talked about it,” Jim Parry described. “Each show was quite a bit different. I would put a lot of folkie things in and Charles, at one point, was fired because he was too ârocky.' That lasted a couple of days and then he was back,” he laughed. “We all pretty much winged it.” Tom Gamache (known as “Uncle T”), who eventually got on the air at '

BCN

in March 1969, thrived on the spontaneity: “I decide what I'm going to play about two minutes before I put it on the turntable,” he told the

Boston Globe

that same month. A lot of Gamache's choices were “the most bizarre,” according to Laquidara. “He blew our minds with Frank Zappa and the Mothers; he turned us all onto âWitchi Tai To'; he was the guy that played Captain Beefheart, John Coltrane, and Roland Kirk. If every station has that guy that pulls the most brilliant songs out of his ass, he was that guy.” J.J. Jackson told

Record World

magazine in 1978, “The jock was allowed to show his personality on the air, and lay out the show the way they wanted. You could play everything from Stockhausen to Alvin Lee; the only record you knew you were going to play was the first one.”

“It was a very mellow presentation,” Sam Kopper described. “A lot of times we were stoned on the air and we came across very gently, very conversationally; that's one hallmark of that time. The other thing I really give due credit to Steven [Segal] and then Charles, was the madness that lasted at '

BCN

into the early nineties. That was laid down at the very beginning.” Segal found the on-air lunacy to be quite normal because “there was so much bizarre stuff happening in real life! For me, I'd just kind of start the

engine and see what came up. It was almost always spontaneous; I never knew what I was going to say on the next break.” As good as he was, “the Seagull” was still inspired by the

DJ

who became one of his best friends, Joe Rogers (as Mississippi Harold Wilson on the air). “Joe did things with nuance, things that came in from completely out in left field. He was a soft-spoken guy who didn't have a mean bone in his body.” He laughed as he recalled an example:

Mississippi had Ian Anderson on; [Jethro Tull] was at the Tea Party and he had to come to '

BCN

for an interview. Ian was a totally unlikable person, an unbelievably arrogant human being, and he was really nasty to Joe. I heard them going on for a few minutes and I remember coming in after Ian had finished being sarcastic and smarmy, and over Joe's shoulder I said something into the mike like, “Are you this nasty to all of the disc jockeys who play your music so people will know what you're doing? Could you ever come in and just answer a question straight without any attitude or acting superior?” For a moment I think he had the starch taken out of him! To this day I know Joe would say that's the way a lot of musicians were, and it's true, but it didn't make it a good thing to do. That was my favorite: basically calling Ian Anderson an asshole.

He added with a snicker, “Did I get that one right or what!”

Early in 1969, the fledgling

WBCN

air staff lost two of its own. A founding rock and roll father in “The American Revolution,” Tommy Hadges, became an absentee jock, only showing occasionally for fill-in shifts, now that he had decided to concentrate on his studies at Tufts Dental School. “Yeah, going back to Dental School, that was a great idea,” Steve Segal kidded glibly. “I said to him, âI can't believe you're doing this!'” But shortly after Hadges's exit, the West Coast guru himself defected, heading back to Los Angeles to be a pioneer on the new underground outlet

KMET-FM

. That promising experience would prove to be so unsatisfying and “corporate,” according to the jock, that he left after only a few months and ended up back on

KPPC

in Pasadena. With Segal's sudden absence, Charles, who had moved in to replace Peter Wolf, now assumed an earlier time slot, while Uncle T and Jim Parry handled the late shifts. As of April 1969, the weekday lineup had shaken out to 7:00 to 10:00 a.m.: Sam Kopper; 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m.: J. J. Jackson; 2:00 to 6:00 p.m.: Mississippi Harold Wilson;

6:00 to 10:00 p.m.: Charles Laquidara; 10:00 p.m. to 2:00 a.m.: Uncle T; and 2:00 to 5:00 a.m. (until the smattering of taped religious broadcasting began) was handled by cleanup man Jim Parry.

Al Perry, who still managed to avoid a good night's sleep by jocking on the weekends and doing overnight fill-ins, was now out on the streets selling ad spots most of the time. Perry, who had become sales manager, recalled that “in the beginning there was me and Jack [Kearney]âcouldn't have done it without him. He was one of the financial cinderblocks of that place, as was Kenny [Greenblatt], who was a real character.” Tim Montgomery, who joined the station two years later and eventually became a sales manager, remembered Greenblatt fondly.

Kenny's job was to interface with the record companies, so his job, to tell you the truth, was almost as important as the program director. He lived in the heart of Harvard Square next door to Peter Wolf, and the only thing he did was hang out with [record company] promo people. He was out and about every night, seven nights a week . . . which is, unfortunately, why he's not with us anymore! He wore moccasins, had long hair, was fond of saying that everything was “far out.” He would twirl his handlebar moustache and say, “Timmy, Timmy, you've got to hear this! It's heavy, it's

far out

!”

The members of the fledgling

WBCN

sales department, as sleepless or as consciousness altered as they might have been, were kicking butt. Ernie Santosuosso noted that fact in his 1969

Boston Globe

article: “The station now has almost $25,000 in ad billings a month, the second-highest for an

FM

station in this area.

WJIB-FM

, an âeasy-listening' station, is first.” Al Perry and his crew achieved this despite the rule set by Ray Riepen that '

BCN'S

commercial load was not to exceed eight ads an hour. Perry noted, “No one believed we could make it; we were the underdogs, not just from a radio standpoint, but a musical one too. All of

FM

radio only had a 10 [percent] share [of the Boston audience];

WRKO-AM

was the king.” That

AM

Top 40 giant alone often pulled in twice the ratings of the entire

FM

band. But even if

WRKO

possessed massive numbers,

WBCN

still had the guns. Al Perry elaborated, “Jack Kearney, J. J. Jeffriesâwho was a jock at '

RKO

, and I, we'd all go out drinking, and J.J. would say, âI was getting laid last night [while] listening to '

BCN

!' No one cool listened to '

RKO

.”

Apparently, though, there were a lot of cool people listening in to '

BCN

,

many of them college students whom the Arbitron ratings service did not survey because of their transient nature. Charles Laquidara recalled, “You could walk from one end of Boston to the other, from Stuart Street all the way to Cambridge, and you wouldn't need a radio because every dormitory, every apartment, all the stores, would have '

BCN

blasting out the windows.” If the station featured a brand-new group or a song that hadn't been released as a single yet, chances were that people were hearing it first on

WBCN

. Sam Kopper told

Boston

magazine in 1970 that over a year earlier, he had witnessed clear evidence of the station's influence with two releases. “The distributor brought us a tape of Traffic's second album four weeks before the record came out. We were the only station playing Traffic, and when the album was released, it completely sold out locally in a few days. After similar prerelease play of Led Zeppelin's first album, the local stores received their shipments in the morning and all copies were gone by afternoon.”

Kenny Greenblatt with Jim Parry on Cambridge Common. Greenblatt worked the record labels for '

BCN

and found an enthusiastic source of income. Photo by Sam Kopper.

Business was going so well at the end of 1968 that Ray Riepen managed to convince Mitch Hastings to give the

DJS

a raise, as Sam Kopper revealed: “We all started at $85 a week, and by early '69 or so, all the jocks were making

$125 a week!” Riepen also successfully pointed out the need to move into bigger digs. Jim Parry elaborated, “Mitch had this dream of having a real radio station on Newbury Street, with that prestigious address, but it wasn't really viable as a station; we ran out of space.”

“We moved to 312 Stuart Street [which] was just above Flash's Snack and Soda and down from Trinity Liquors,” Sam Kopper added. “Charles went to work just as we moved, right at the end of 1968.” The new location, nestled behind the bustling Greyhound Bus terminal, would be

WBCN'S

home until June 1973. Flimsy and cheap quarter-inch paneling notwithstanding, the layout was much more conducive to running a radio business, with accessible areas for reception, sales, and management; studios in the back; and the record library across the hall. Perhaps best of all, the

DJS

had escaped their claustrophobic Newbury Street attic; they wouldn't freeze during the winter months or roast in their own sweat next to a loud and impotent air conditioner during the summer.

As

WBCN

settled in on Stuart Street, some fresh voices appeared on the air. John Brodey, who would eventually become a radio star in his own right and a future music director, had listened to '

BCN

with great interest during his frequent visits home from the University of Wisconsin to see his parents in Boston. “I knew a girl who had gone out with Steven [Segal] for a while and I said, âIf you can just give me an introduction, I'll take it from there.' Soon I was interning for Steven, weaseling my way in. I had to put away his records, get him stuff, and drive him home because he had a car but didn't drive. We started talking, and soon it was: âOh, you know something about music, man.' It was a nice relationship and . . . I lasted!”

Sam Kopper also hired Debbie Ullman to be

WBCN'S

first female jock after she had worked with the close-knit crew in the sales department for a time and also volunteered to helped transport the station's voluminous record library from Newbury to Stuart Street. “I liked her voice, intelligence, and spirit,” Kopper mentioned. He was also impressed when she took the initiative to study for and pass the

FCC

exam for a radio license, not necessarily an easy thing to do, and unusual, at the time, for a female. “I was the only woman out of about forty taking the exam; afterwards the guy looked over my test and was startled.” So now she had the endorsement of Uncle Sam, but did she have the chutzpah to do a show? Kopper decided to find out. As Ullman worked in the sales area one afternoon, the jocks arrived for an air

staff meeting. “That usually meant that someone would play long tracks on the radio, like a Grateful Dead side, while they met,” Ullman remembered. “On this occasion someone came [to me] and said, âWe're going to have a meeting in ten minutes; if you can learn the [air studio] board, you're on.” She wasn't thrown by the challenge. “I'd already been watching [the other jocks use] the board . . . so that wasn't hard. I went on while they had their staff meeting; apparently, I didn't fumble things too badly!”