Radio Free Boston (34 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

Epic Records brought Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble to Boston in February 1987 and handed over all 1,250 tickets for the Austin rocker's show at the Metro to

WBCN

. Since the guitarist had played the much-larger Orpheum Theater the previous year, this was a special, more intimate visit, and all the tickets were given away on the air. Vaughan and his band also dined with the '

BCN

jocks at Davio's Restaurant on Newbury Street, where owner Steve DiFillippo had fostered a reputation for fine Italian food and impeccable service. Ken Shelton sat at the table with Vaughan that night: “He had his manager call over to Davio's [and ask], âI wonder if your chef could whip up some rabbit?'” There was no doubt that the first-rate eating establishment possessed a splendid and well-varied menu, but like most New England restaurants, hare wasn't on it. To Shelton's amazement, though, the guitarist's crew had prepared for such an eventuality: “Vaughan's roadie had a case of fully skinned, fully cleaned rabbits with him! And the restaurant didn't even blink; they prepared it! Now that's a true Italian chef, not just your usual spaghetti and lasagna guy.”

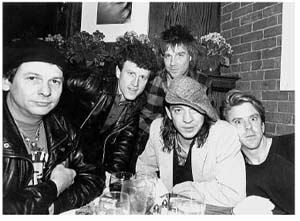

Stevie Ray and Double Trouble digesting with Oedipus and Carter Alan at Davio's.

WBCN

displays major mojo by giving away all the tickets for the band's 1987 show at the Metro. Photo by Ron

Pownall/RockRollPhoto.com

.

The air staff up close and personal with Aerosmith at the free

WBCN

show in the Worcester Centrum, 1986. Happy eighteenth birthday to the Rock of Boston! Photo by Ron

Pownall/RockRollPhoto.com

.

Perhaps the foremost benchmark of this,

WBCN'S

second age of Camelot, occurred in 1986 when the station celebrated its eighteenth birthday by giving away all thirteen thousand tickets to a free concert with Aerosmith at the Worcester Centrum. The band had gone through some hard times by the end of the seventies as the members split into factions, largely as a result of prolonged (and well-documented) drug abuse, but had reassembled with a new label, a fresh resolve, and an album entitled

Done with Mirrors

. Now on the comeback trail, Aerosmith had never lost its longtime connection to

WBCN

, which could be traced all the way back to Maxanne Sartori's enthusiastic support; plus, Joe Perry and the band's manager Tim Collins shared a strong personal friendship with Mark Parenteau. “We always had the first link to Aerosmith,” the

DJ

mentioned. “I would always get the spontaneous interviews with Steven, my name was always in the credits, and '

BCN

would get first knowledge of any concerts they were going to do. I know a couple of other stations wanted to be a part of all that, but for sure, we were the favorite.” When the idea materialized for the band to perform a special show to commemorate '

BCN'S

long history and legendary status, the group eagerly agreed.

In the official

WBCN

press release, Joe Perry stated, “The free

WBCN

show is another gift to the people from Aerosmith, the people's band.” Steven Tyler added, “The buzz on this concert is like lending the family parrot to the town crier. The excitement we feel about this show is phenomenal. You can't buy it or bottle it. It's a pleasure to be making history with

WBCN

.” The concert itself was a dizzying peak of excitement for all the '

BCN

jocks who assembled onstage before Aerosmith “let their music do the talking.” Once they had received the keys to the city of Worcester in a small official ceremony, each member of the lineup was introduced to the audience and recognized individually by Charles Laquidara; then, a memorable photo shoot caught them all in front of the cheering crowd. Later, during Aerosmith's set, the band invited everyone back onstage for a rousing version of “Happy Birthday,” while candles spelling out

W-B-C-N

burned brightly on a gigantic cake. It was a moving moment for everyone gathered on that stage, and even the veteransâLaquidara, Shelton, Parenteau, and Berardiniâknew that this moment was as good as it could ever get.

“You never knew [who] you were going to run into in the hallways: Jerry Seinfeld, Aerosmith, chefs, a new group, or the old band. When David Lee Roth came to the station, there were people hiding under cars in the garage trying to get upstairs for an autograph!

“METAL MIKE” COLUCCI

FROM

BOYLSTON

STREET TO

WALL STREET

By the mideighties, the Fenway Parkâfacing, rear garage-door entrance to

WBCN

had seen thousands of arrivals and departures, carefully timed to avoid the unsportsmanlike panic of Red Sox Nation traffic. Access from the dank garage and up the dangerously pitched stairs to the offices and studios above took one past the graffiti wall, where employees and stars were encouraged to spray paint their names and messages to posterity. “That graffiti said a lot about what '

BCN

was,” weekender Lisa Traxler mentioned. “Everybody added to that.” The freedom of expression, whether directed toward a small quadrant of cement-block wall with aerosol paint can in hand or aimed heavenward through a microphone and turntable (or the newfangled compact disc player that had just shown up), were one in the same. “I liked Oedipus's analogy,” Tami Heide remembered: “All the jocks at '

BCN

have the same brushes, the same paint, and they're given the same canvas. But they all have their own brushstrokes; it's just how they put it

together.” Protected in their studio, the

DJS

labored over their portraits, even as forces arrived that threatened to limit whatever freedom had been carefully earned during two decades of survival. Challenges loomed from inside the rapidly expanding Infinity empire, as well as outside from a cloud of seasoned competitors and new players in the market.

Infinity Broadcasting had binged on acquiring stations, leaving the company cash poor by 1986. Subsequently, Michael Wiener, Gerald Carrus, and Mel Karmazin took the company public, offering up its common stock to shareholders and raising millions in capital. They used the money primarily to reduce Infinity's long-term debt, which had been accrued when borrowing to buy stations, and to provide funds for accumulating additional properties. Within a year of the public offering, Karmazin went on to purchase six more stations:

KROQ-FM

in Los Angeles,

WJFK-FM

in Washington, D.C., and two

AM/FM

combos in Tampa and Dallas. Even with the sale of Infinity's Jacksonville property and a pair of San Diego stations in December 1986, it was a dizzying expansion. By the time of the company's annual report to its shareholders in spring '87, the number crunchers could claim that “Infinity is the nation's largest, publicly traded,

radio-only

owner and operator of stations.” The report further revealed that Infinity had taken in “$1.4 billion in radio advertising revenues (approximately 20% of the total $7 billion spent for radio advertising in the United States).” Although just one part of a massive and highly valuable corporate entity now stretched coast to coast,

WBCN

was certainly not a diminished commodity; in June 1988, the

Boston Phoenix

disclosed, “The station that Infinity picked up for $3.5 million in '79 is valued today at an estimated $75 million to $80 million.”

“I really didn't understand the finance part of it and what it meant to be [a publicly traded company],” Tony Berardini recalled. “What it meant on a day-to-day basis at

WBCN

was that there was a lot more pressure for us to make our numbers; things became more intense. Being a public company that now reported its earnings quarterly, Mel had to stand up in front of the stockholders and answer questions, and God help you if Mel had to defend your sorry ass.”

Bob Mendelsohn remembered, “There were these quick outbursts [from Mel], not necessarily from anger: âHere's what I need and I'm not getting it! How are we going to keep our stock price up? How are going to keep to our acquisition plan without generating revenue?' It was always a high-wire act.”

Berardini added, “We were in a meeting one time with a general sales manager who wasn't making his budget, and he was saying, âWell the ratings are this and the business cycle is bad . . .' Mel says, âHey, listen! Don't sell spots, then. Go stand on the front steps with some pencils. Sell the pencils and book that as revenue. I don't care how you make it!'”

“Mel Karmazin was never part of the '

BCN

culture, never part of the counterculture; he was a money man,” Katy Abel commented. “I mean, nobody said Mel was a teddy bear, but he was a genius at making money, and if that's what mattered to you, then he was your guy.”

“Once they gave Mel Karmazin the job of making the most money in the shortest amount of time with the fewest amount of people, the bottom line was the bottom line,” Charles Laquidara summarized.

The business world learned to respect Karmazin and his upstart Infinity Broadcasting Corporation, and even though the company still carried an enormous amount of debt with its recent station acquisitions, the amount of revenue its properties generated grew. Tony Berardini revealed that

WBCN

, the station whose equity had initially financed the growth of the empire, posted 14 percent of Boston's entire radio market revenues in 1986. It was a phenomenal figure, considering that more than two dozen radio signals crowded the city's airwaves. With numbers like these, the future of Infinity seemed only positive at the New York Stock Exchange where its shares were traded daily. That rosy outlook held firm until “Black Monday” on 19 October 1987, when the market abruptly crashed, losing over 20 percent of its value and heralding a major U.S. recession. Even so, it was business as usual at Infinity's corporate headquarters, which meant more pressure on the local level. “Mel wouldn't accept any of those [excuses] . . . like business cycles, the âCrash of '87,'” Berardini stated. Karmazin's enormous force of will, though, couldn't prevent the sluggish economy from pulling down profit margins at most stations and forcing a net loss at others. As Infinity's stock sagged, the chief remained adamant that the market was undervaluing his company, so with others in the corporate management team, Karmazin borrowed the capital needed to buy back Infinity, taking it private again in 1988. Berardini commented, “His attitude was, âFine . . . the market doesn't value us? We value us!' And he went out and bought all the stock back.” Despite the increased debt load, Karmazin's strategy paid off as he waited out the recession, and his critics, and then took the company public again in 1992 for a huge cash

windfall that he used, again, to pay down Infinity's debt and provide funds for expansion.

During the late eighties,

WBCN

continued to thrive, though the tough economic situation made the demands from corporate all that much more difficult to address. “[Tony] was the focal point for all that pressure.” Bob Mendelsohn observed. “His whole job had become one of somehow squeezing all the parts together so that nothing would get hurt too badly and he could still give Mel what he wanted.” Even so, Berardini's responsibilities increased dramatically in February 1987. After being promoted to a company vice presidency and retaining his general manager (

GM

) duties at

WBCN

, he was also given the responsibility of heading up

KROQ

in Los Angeles. Bob Mendelsohn smiled wryly at the memory: “Infinity was the land of the two full-time jobs. Tony did it. I did it . . . for a year and a half: general sales manager

and

national sales manager.” The official

WBCN

press release stated that “Berardini will now direct the activities of both stations, dividing his time between Infinity's Boston and Los Angeles affiliates.” This meant that the music geek from the Bay Area who had arrived at '

BCN

in 1978 behind the wheel of a

VW

hippie bus was now going back out to the West Coast, wielding Infinity's hammer and sickle while still responsible for a station three time zones behind him. The bicoastal

GM/VP

started logging astronomical frequent-flier miles, jetting to

LA

for two weeks and then returning to Boston for the rest of the month. “Mel didn't tell me to do it that way; it was the pattern I established. I had a company car here and one out there [two âheavy-metal' black Pathfinders]; I'd fly in on Monday, get there at noonâLA time, go right to the office and then work until six. Then the next day I'd be in the office at

KROQ

between 6:00 and 6:30 each morning; I'd deal with '

BCN

issues and talk to them first, then

KROQ'S

people would come in later.”

Despite Berardini's physical absence half of the time and the world's economic woes, as

WBCN

reached its milestone twentieth birthday, morale couldn't have been higher.

Adweek

magazine ran a story that month entitled “

WBCN

Remains Solid as a Rock after 20 Years: Radio Advertisers Find the Boston Station a Sure Bet in a Fickle Market.” The article cited '

BCN'S

remarkable ratings consistency: “First among men 18â34 and 18â49 for 22 Arbitron surveys running [four per year]. In the adult categories [men plus women] for those age groups, it has ranked first for 20 surveys.” Governor Michael Dukakis and Mayor Ray Flynn both declared Tuesday, 15 March

1988, “

WBCN

Day” in the state of Massachusetts and the city of Boston, officially marking a farewell to the teens for “The Rock of Boston” and the opening of its third decade as an

FM

powerhouse. Peter Wolf returned to the airwaves for his annual “Houseparty” show of R & B hits and rock and roll memories, while Maxanne Sartori, Eddie Gorodetsky, and Danny Schechter also delivered guest spots throughout the day. The station's twenty-year milestone was underscored by a motor head's wet dream of a contest, the station giving away a 1988 Pontiac Trans Am as well as a sweet 1968 Pontiac

GTO

classic. In San Francisco, the annual Gavin Awards and Seminar for Media Professionals feted

WBCN

as national “Album Radio Station of the Year” for the third consecutive time.

Peter Wolf's Houseparty! Taking over the '

BCN

airwaves in the name of rock and roll with “the platters that matter!” Photo by Mim Michelove.

Charles Laquidara, Ken Shelton, and Mark Parenteau had settled into every weekday for most of the decade; Tami Heide now handled nights beginning at six; Bradley Jay, at ten; and Albert O rode the a.m. hours from two until “The Big Mattress” crew once again tumbled in before dawn. “Weekend warriors” included former newsman Steven Strick (who had returned after four years to be a jock), Lisa Traxler (a ballsy midwestern

admirer who had driven east unannounced to pitch Oedipus on a '

BCN

gig), Shred (a dedicated local-music fanatic), Peter Choyce (known for his off-beat graveyard-shift witticisms), and “Metal Mike” Colucci (who produced Tony Berardini's “Heavy Metal from Hell” program). I became the station's full-time music director, replacing Bob Kranes, and trading my regular weeknight shift for a single one on Saturdays. The music meetings, fueled by our prevailing idealism to use this marvelous vehicle to turn people onto new sounds, continued. In Oedipus's case, he had a weakness for female artists (Tami Heide dubbed them “Oedi's Women in Pain”âand it stuck); Kathryn Lauren (who did nights for three years) loved any novelty record (“spastic plastic” is what she called them); Albert O might pitch a Robin Hitchcock single; Bradley, his eternal favorite Bowie; or I might be arguing for the new Big Country or the Alarm cut. Collectively, we actually liked it all (well, maybe not Kingdom Comeâeveryone hated them). “'

BCN

was fun and craziness, and a lot of political content too,” Lisa Traxler remarked, “but music was an important part of the triad. Everybody, no matter what they might disagree on, had tremendous respect for the music, and musicians.”

Tony Berardini, handling the business in his pressure-cooker general manager position, let off steam during his weekend “Heavy Metal from Hell” program. “Metallica came to the show in 1988 during the âMonsters of Rock' tour; that was very cool. My favorite moment, though, was when Lemmy from Motorhead came up to be guest

DJ

. I figured he'd play all heavy stuff and Hawkwind, but all he wanted to spin was Motown!”

“Guns and Roses were in town playing the Paradise,” Metal Mike remembered. Hired to the Listener Line in '86, he was filling in for Berardini on the air a few years later. “They had what they called a preshow press conference, which consisted of Axl and the guys pouring drinks in Stitchesâthe front room of the Paradise. I had just turned eighteen and Duff poured me a sixteen-ounce beer glass of vodka, then added just a touch of orange juice. This was three o'clock in the afternoon! Before I knew it, the âDise show was on; it was like a freight train running through the neighborhood.”