Radio Free Boston (38 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

On 28 February 1993,

WBCN'S

staff gathered at the Hard Rock Café in Back Bay to celebrate the station's twenty-fifth birthday. Invitations had gone out to current workers as well as all the former employees who could be found. “It began with Carla Wallace, an original '

BCN

person at Stuart Street,” David Bieber explained. “She called me in December '92 and said that we should do a twenty-ffth-anniversary party.” It seemed like an obvious idea, but Wallace had the additional vision that the party should be open to anyone who had ever worked for '

BCN

. The happy result was that four hundred employees jammed into the Hard Rock, their buzzing conversations easily drowning out the blaring music, that is, until the members of the J. Geils Band found their way to the stage and serenaded the crowd with an a cappella version of “Looking for a Love.” It was the band's first public performance since it had broken up a decade earlier and a symbol of respect, not only for singer Peter Wolf's former radio home, but also for the long lineage of legendary characters that had inhabited 104.1

FM

. Stars from former times arrived in force: J.J. Jackson, Tommy Hadges

(now president of Pollack Media Group), Billy West (the voice of the

Ren and Stimpy

show),

WBCN'S

founder and original owner Mitch Hastings, Danny Schechter, John Brodey (a general manager at Giant Records in

LA

), Norm Winer (a program director in Chicago), Maxanne Sartori, Ron Della Chiesa, and Eric Jackson. Aimee Mann, James Montgomery, and Barry Goudreau of Boston mingled about. Susan Bickelhaupt queried in her

Boston Globe

article about the anniversary, “25 years later, what has replaced rock station

WBCN-FM

? Nothing. It's still '

BCN

, 104.1. Sure the jocks are older and drive nicer cars, and you can even buy stock in parent company Infinity Broadcasting, which is traded on the

NASDAQ

market. But the station that signed on as album rock still plays album rock, and is perennially one of the top-ranking stations and a top biller.”

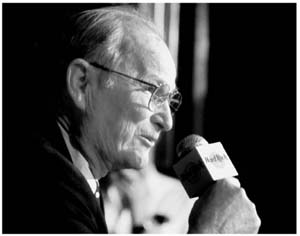

T. Mitchell Hastings addresses the crowd at the Hard Rock Café in 1993 for

WBCN'S

twenty-fifth anniversary. Photo by Dan Beach.

A rumor passed about the room that night, given weight since it allegedly came from a

WBCN

manager: something major was going to happen with one of the station's primary weekday air shifts. Since lineup changes at the station occurred with the frequency of Halley's Comet appearances, this

warranted front-page news (or, at least, endless speculation). Was a member of the famed daily triumvirate of Laquidara, Shelton, and Parenteau finally bowing out? Oedipus and Tony Berardini weren't talking, but their conspicuous silence seemed to support that something big was about to happen. Industry analysts caught a whiff of the rumor as well, but it came from a different source: New York, on the nationally syndicated Howard Stern show. In the years since the former Boston University student had attempted to find work at '

BCN

, the announcer had made his mark outside of Boston, rapidly rising to become a hurricane force in radio with his undeniable wit, lapses of taste, and incessant sparring with the

FCC

over established indecency boundaries. The shock-jock had always desired to return to Boston, hinting that this might be a possibility in the near future, but the official confirmation of that did not arrive until 8 March 1993. That night,

WBCN

began airing Stern's nationally syndicated morning show, on tape delay, following Mark Parenteau's afternoon shift.

Tony Berardini told

Virtually Alternative

in 1998, “Howard Stern was doing extremely well at Infinity's

WXRK

, and then at 'YSP, Philly. Oedipus and I kept looking at it, thinking, âWow, the company is going to want to syndicate him in Boston, too, why wouldn't they?' It was one of those things we knew we were going to have to deal with, yet Charles Laquidara still had good numbers in the morning. Even Howard used to listen to him when he went to Boston University. With this in mind, we went to Mel with the idea of running his show by tape delay at night. We had an immediate opportunity there, and we decided to take advantage of it.”

“Howard wanted to be on the radio in Boston, and I was able to make that happen because I could put him on at night,” mentioned Oedipus. “Everywhere else [with the exception of

KOME

in San Jose], he did the mornings, but Mel allowed me to make the decision to tape the show and play it later.” Oedipus did not regret his decision: “Howard is a monumental talent; it just can't be denied. I remember many a time driving home from work and then just sitting in my garage, not getting out of my car, because I didn't want to miss a moment.” Listeners tended to react to Stern's show simply and starkly: they either loved the

DJ

or hated him. Those who disliked his presence on

WBCN

found other nighttime options, but those attracted to his brand of radio comedy became riveted . . . for long periods of time. “Nighttime listening to rock stations was really falling off at that time, and we had nothing to lose,” Tony Berardini told

Virtually Alternative

. Very

quickly, as nighttime ratings at

WBCN

increased dramatically, the gambit, it seemed, had played out to be a shrewd and successful decision.

“Metal Mike” Colucci was one of the part-time employees now called upon to man the studio each weeknight, acting as a board operator during the taped Howard Stern program. Although just a lowly, anonymous worker bee to the mighty Stern, Colucci would be elevated by that jock's rabid following to the status of infamy. This was one of the secrets of that show's success: the shock-jock's ability to whip up drama, creating form and substance out of something that, when examined more closely, really warranted no such time or attention. Who cared? In Stern's hands, though, it seemed that a lot of people actually did (at least for four or so hours a day). On the evening of 27 July 1993, Reggie Lewis, a twenty-seven-year Boston Celtics rising star, collapsed on the court and died from a heart defect while Howard Stern's taped program ran on

WBCN

. Shocked, Mike Colucci phoned Oedipus to ask what to do. “He told me, âFade out Howard, play “Funeral for a Friend” [by Elton John] and announce that Reggie Lewis is dead.'” However, as an inexperienced

DJ

, Colucci couldn't handle the wave of emotion that swept over him as he spoke on the air: “I got all choked up; I went into this terrible tailspin before I got back into Stern's show as fast as I could.” Unbeknownst to the young board op, one or more of Howard Stern's ardent Boston fans taped the show and overnighted a recording to the shock-jock for his live broadcast the following morning. Stern played the tape on the air relentlessly, downplaying the drama of Lewis's death to focus on Colucci's painful on-air gaffe. “It turned out that he did forty-five minutes on me, saying things like, âIf this guy is acting, he's a genius.' Red faced, he endured the episode over and over again, taking a lot of good-natured ribbing from a host of people who never even heard the original episode. “At the time, Howard had the biggest radio antennae going; nobody was going to break in on his broadcast. He could stick it wherever he wanted.”

Many employees and fans of the station disagreed with the strategy of adding Stern to the

WBCN

lineup, finding the move troubling, at the very least. Bob Mendelsohn, as general sales manager, would work intimately with the new syndicated show, selling airtime to local and national clients: “The first time I heard Howard Stern, I hated it. It just embarrassed me. It wasn't his sense of humor; it was his complete elimination of standards. These were the boom years; everything was about stock price and profits now.”

“When Howard Stern got [to '

BCN

], it was all about how much money he was making [for the company],” Danny Schechter observed. “These were the values of Mel Karmazin. They didn't really care about Boston, [and] they didn't really care about the audience; it was the market and getting market share. That's what mattered to them: it was about the shareholders.”

“I know a lot of people mark Howard Stern as the beginning of the end, and maybe it was,” Tim Montgomery said. “Because, in a way, Ken Shelton and his Lunchtime Salutes [and] the crossovers between Charles, Ken, and Parenteau: that represented the old '

BCN

. God, there was some brilliant radio! Then, with Howard Stern and the whole coarsening of the culture, the station took on that mean, macho, sexist [attitude] with eighteen-year-old-boy fart humor and vagina jokes. That's not what '

BCN

was! It was smart; then it became stupid. The dumbing down of the '

BCN

audience became the whole new thing.”

“That Mel had this amazing asset in New York and then was able to multiply that asset by putting it on all these stations, as a corporate move, bordered on brilliant,” Bob Mendelsohn admitted. “But it was

everything

that '

BCN

had

never

been before.

WBCN

had always been credible and sincere; this was smart-ass radio. As an employee of the station, that's when my affection and my pride in working there started to go in a different direction.”

A second seismic event that shook

WBCN

in 1993 had been simmering since the year before, when Infinity Broadcasting, which owned and operated eighteen radio stations at this point, had entered into an agreement to purchase

WZLX-FM

in Boston. The $100 million deal with Cook Inlet Radio included the acquisition of two other radio properties in Chicago and Atlanta, and was made possible by another relaxed ownership edict from the

FCC

that increased the number of radio stations a company was permitted to own. Previously, a single operator could only possess a total of twelve

AM

stations and twelve

FMS

, but those limits were increased to a total of eighteen

AMS

and eighteen

FMS

. Additionally, the previous rule that a single operator could own a maximum of one

AM

station and one

FM

in a single market was increased to two each, as long as there were fifteen or more radio properties in the area and that listener share did not exceed 25 percent of the market's total. Infinity chomped at the bit to take advantage of these revised, business-friendly rules: although the

FCC

edict did not go into effect until 16 September 1992, the company proudly

trumpeted its pending purchase in an 17 August press release. Obtaining final

FCC

approval would push Infinity's official takeover of

WZLX

into '93, but when all was said and done,

WBCN'S

biggest rival had suddenly been made a member of the same family. The two stations had been kicking each other under the table since the mideighties, but Mel Karmazin now demanded that the horseplay stop immediately. “The day that [Infinity] closed on buying

WZLX

, [Karmazin] got the sales managers from both stations together for a meeting,” Mendelsohn recalled. “His message was, âYou guys have been out on the street trashing each other for years. As of today, that stops; you're working together.'”

Not only did the new association with

WZLX

mean that the sales strategies at both stations could be allied and results maximized, but Oedipus now had the opportunity to collaborate with his former adversary, program director Buzz Knight, in working out a two-station approach that minimized the considerable musical overlap of their respective formats. This appeared to be the answer to

WBCN'S

programming dilemma of addressing the tastes of two steadily diverging radio audiences. “This is what happens when you have a radio station whose life is so prolonged; you outgrow your audience,” Oedipus pointed out.

WBCN

could either grow old with those longtime (twenty-five- to fifty-four-year-old] fans, becoming essentially a classic rock radio station, or embrace the younger listeners who were moving into the station's demographic target. With

WZLX

in the mix, the decision essentially became moot. “We elected to stay younger;

WBCN

had to. We focused on the eighteen- to thirty-four-year-olds.” Making that transition would occupy a year or so, but the first adjustment, proposed almost immediately, became the station's third seismic shakeup in 1993.

Along with conducting the necessary music and image modifications to focus on the younger eighteen- to thirty-four-year-old segment of its audience, the managers at

WBCN

now turned to reassess the soundness of their air talent. “

WBCN

had been as important to Boston as the

Globe

and the Red Sox; we were an institution,” Oedipus observed. “But now, nineteen- and twenty-year-olds could no longer relate; they wanted something else.” The program director referred ominously to the sacrosanct “Big Three,” intact and in place on '

BCN'S

weekday air since 1980. At the moment, Laquidara and Parenteau were winning their respective battles, even with the younger listeners, but a shadow of scrutiny had now fallen on Shelton's shift. “Oedipus called me one day and said, âI need to talk to

you after your show,' the midday man recounted. “He said, âYou've been great and we love you. It's been such a perfect fit, gliding from Charles's insanity to Parenteau's wildness, the calm between the storms. But the company just bought

WZLX

, and there's a big master plan; there's going to be lots of changes.'” Shelton suspected what was coming next: that “master plan” probably included moving some or all of the '

BCN

old-timers over to the classic rock station. “Oedipus said, âYou're the highest-paid midday guy in America. Your contract is up in a year; you're welcome to stay and keep doing what you're doing. [But] Mel loves you; he thinks you could be a [good] morning man. How about doing mornings at 'ZLX, with more money?'”