My Guantanamo Diary (8 page)

Read My Guantanamo Diary Online

Authors: Mahvish Khan

Today, the

Korematsu

case is viewed as a sad blemish on the history of the U.S. Supreme Court. I was taught that it represented everything the high court should not do: allow pressure and fear to strip people of their legal and human rights.

But history repeats itself. Many of the Guantánamo detainees were taken from their families and homelands, many from their own beds at night, brought halfway around the world, tortured, and held in secret, without charge or trial. The Guantánamo cases raise lasting and fundamental questions about America’s willingness to abide by its principles and adhere to the rule of law, especially when under threat. Not long before he died in March 2005, Fred Korematsu filed another brief before the U.S. Supreme Court, this time on behalf of hundreds of Muslims being held at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

I wrote about my first trip to Guantánamo, and my feelings of shame when I met a pediatrician and an eighty-year-old paraplegic who asked me why the United States hid him from the world and from journalists, in an article for the

Washington

Post

that was reprinted in newspapers around the world. I received an outpouring of e-mails from readers. Of nine hundred messages, about twenty were hate mail. One reader suggested that I might be working for “the enemy.” Another told me that I was being duped by al-Qaeda manual-reading terrorists. But the vast majority of responses were from regu-

lar Americans who felt just as deceived by our country’s actions as I did.

Shortly after the story ran, I received an unpleasant phone call from the Pentagon telling me that I was being banned from the base. I was upset. I’d been extremely careful only to publish information that had been reviewed and declassified by the government. I’d also been careful not to violate the protective order of military base rules governing Guantánamo Bay, which I’d been required to sign. I knew I hadn’t done anything wrong, but I wasn’t sure how to handle the situation.

I received a flurry of e-mails from various habeas attorneys advising me to do different things. Many suggested that I hire an independent attorney and file a lawsuit. I decided not to fan the flames and instead to call the Pentagon official back and ask him why I had been banned. I got a voicemail the first time and left a message asking for an explanation. Then, I decided it would be better to have a written record, so I e-mailed and called again.

Essentially, I was told that my base privileges had been revoked because my

Washington Post

article had created a security and safety threat to the base, as well as to the individuals who worked and lived there. I was told that I was in violation of the protective order I had signed because I had published a photograph of the sun rising over the hills in Guantánamo and because I had printed the name and photograph of a military escort.

I knew there was no protective order violation; several attorneys had helped me comb through the entire document. Furthermore, my photograph of the Guantánamo landscape could not have been any more of a security threat than any of

the real-time Internet satellite and aerial photos of the base. I think DOD officials were just looking for a reason to ban me because of the negative publicity the article generated.

This began a two-month-long back-and-forth of negotiations via e-mail and telephone. Once, I tried joking with the DOD guys, telling them that in the spirit of the giving season (it was Christmas), they should reconsider their position. I’m not sure what finally convinced them, but eventually, I was instructed to write and sign a statement saying that I would not photograph the base or military personnel. I also apologized profusely for creating a security threat by publishing a Gitmo soldier’s photo. And I promised never to bring a camera onto the base. I said whatever I had to get my privileges back. But I also pointed out a recent article in a scuba diving magazine that included lots of photos of some of the camp’s X-ray guards, complete with their full names in the captions.

On June 8, 2006, base commander Adm. Harry Harris wrote me a long letter. It was on DOD letterhead, and it was harsh. It scared me. But at the same time, I felt that it was a kind of honor to have been reprimanded by the Gitmo base commander. I knew I hadn’t violated the protective order as they claimed, but I’m thankful that I hadn’t been accused of wearing a Casio watch or staying in a guesthouse.

I had the letter framed and hung it in my bathroom, right above the toilet.

THE GOATHERD

I know it’s not good to play favorites, but I couldn’t help it. Of all the detainees we worked with, I most looked forward to the meetings with Taj Mohammad. Taj, No. 902, was a twenty-seven-year-old goatherd from Kunar, Afghanistan, who formed crushes on his female interrogators and had taught himself perfect English in his four years at Guantánamo.

It’s not that I liked Taj better than the other detainees. They’re all different. But he was easy to talk to, and he made me laugh. I felt sorry for Haji Nusrat, who was old and sick, and for Ali Shah Mousovi because he was so polite. But Taj was my age and loaded with personality. Unlike the others, he rarely came across as vulnerable. He was highly opinionated and very sarcastic. Even his misogyny was somehow comical. I’m sure he would have gotten on my nerves if I’d spent more time listening to his sarcastic wisecracks, but in our limited contact he was pure entertainment.

In our meetings with Paul Rashkind of the Miami Federal Defenders, Taj’s attention was always drawn to written English. He would sound out the lettering on coffee cups and napkins, and when legal papers were put on the table, he would immediately start reading under his breath.

He asked us repeatedly to bring him a Pashto-English dictionary so that he could improve his English. Over several months, he had compiled and memorized a list of almost one thousand English words. But during a routine search, the guards had found and confiscated his neatly written glossary.

When Paul told him it was unlikely that he’d be given permission to bring him a book, Taj looked unhappy.

“If you can’t bring me a book, how do you plan on getting me out of here?” he said. “Even the interrogators give us magazines.”

I asked what kind of magazines.

“

Playboy

,” he said.

I’d heard the same from guards at the Clipper Club, who said that lots of detainees made associations between American women based on what they saw in the soft-core men’s magazine

Maxim

.

Sometimes the guards helped that along, it seemed.

At the beginning of my second meeting with Taj, he pulled out a small piece of creased white paper and handed it to me. “I told the guards that the girl who speaks Pashto is coming, and I asked them to make a list of words so you could translate them for me,” he said.

My jaw dropped as I scanned the list. “What does it say?” Taj asked. “Tell me.”

The first word on the list was “bestiality.” The second was “pedophile,” the third was “intercourse,” and the fourth was “horny.”

“I think those soldiers have played a little trick on you and me,” I smirked.

“Tell me,” he persisted. “What did they write?”

“I don’t know how to say these words in Pashto,” I responded. “I learned Pashto from my parents.”

Taj’s eyes widened. “Okay, just tell me one of the words,” he insisted.

“I don’t know them,” I said.

“Then, tell me what it means.”

I scanned the words again.

“Bestiality means showing

meena

—affection or love—to one of those goats you tend,” I said smiling. “But it’s not a good sort of

meena

.”

Taj let out a laugh. He got the picture. He grabbed a pen from the table and scribbled something in Pashto next to “bestiality.” That’s when I realized that he had probably known the nature of his vocabulary lessons all along.

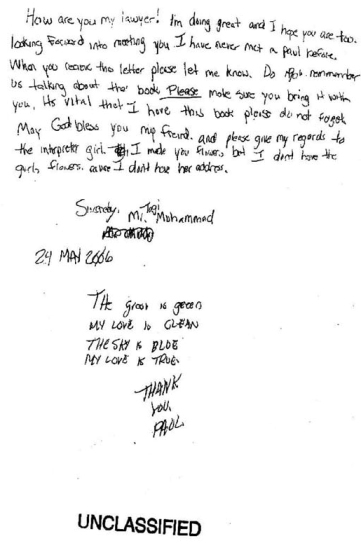

Taj’s command of English was amazing. When I later saw a May 24, 2006, letter he’d written to Paul, I thought he had to be a goat-herding genius. Or at least a highly educated goatherd. He sounded very American. His grammar and punctuation were perfect. He indented properly and started each sentence with a capital letter. He even underlined for emphasis.

Of course, I suppose it’s also possible that one of the government interpreters helped him write the letter. Taj said he’d learned a lot of English from Abdul Salam Zaeef, an

ambassador to the Taliban, when he was held in Camp 4. And he also practiced as much as he could with the guards.

Taj sent me a letter at one point, with a drawing of flowers and a poem. I’d share it, but the DOD wouldn’t declassify any poetry or art for fear that it might contain coded messages for terrorists. The Pentagon did, however, allow one poem that Taj wrote in a letter to Paul to slip through.

- The grass is green,

My love is clean.

The sky is blue,

My love is true.

The first time Paul and I met with Taj, he was sitting behind a long table. One leg was extended, and he was dressed in white, which meant that he was being held in Camp 4. He had longer hair than the other detainees and pushed it behind his ears to keep it out of his face.

He casually asked who paid Paul’s salary and whether he was employed by the U.S. government. This is a tricky subject for federal public defenders to address. They must truthfully convey that although they work for the government, their decisions remain independent. Naturally, many detainees have a hard time accepting that someone can act in their best interests when they’re being paid by the same government that’s imprisoning them.

Paul worded his answer carefully, explaining what kind of law he practiced, who his regular clients were, and, above all, that he was in no way influenced by the U.S. government.

Taj Mohammad’s letter to Paul.

“I work for you,” he said to Taj with a smile.

“What benefit is it for you to help me?” Taj asked suspiciously. “What do you get out of it?”

Paul explained that not all Americans agreed with the actions of their government and said that he wanted to help Taj receive a fair hearing and get him released one day.

Taj was having none of it. “You’re really here because you want people to see you as a big lawyer who represented the famous Guantánamo detainees, right?” he said.

This back-and-forth continued for a while. It was difficult for Taj to conceive of why an American whose government had declared Guantánamo detainees a threat to U.S. national security would want to get involved.

“Is this going to help your business when you tell people you freed a man from Guantánamo?” he challenged Paul again.

Taj’s quick wit and efforts to shock amused me. He didn’t bother trying to be polite, like the other Afghans, and he didn’t sugarcoat anything.

“I don’t think a lawyer can get me out of here,” he declared. “A lot of detainees have been released without the help of any attorney.”

But he listened as Paul explained why it was beneficial to have an attorney. Without one, he would be hidden from the world, subject only to the U.S. military. “An attorney is like chicken soup,” Paul said, looking for a metaphor. “It can help you to have one, and it’s definitely not going to hurt you.”

Finally, Taj relented and began to ask questions about his habeas petition.

“Is the judge on my case a man or a woman?”

“Your judge is a man.”

Taj held two thumbs up and broke into a smile.

“What do you have against women?” I blurted. In spite of myself, I felt annoyed at his display of glee over not having a female judge.

“Nothing,” he said. “I like women, but no one listens to a woman.” And he gave me a grin.

Taj had been arrested in late 2002. Although he hadn’t been formally charged, the U.S. military accused him of associating with the Taliban and al-Qaeda and of taking money to attack a U.S. base. Taj maintained that it was all nonsense. He was a goatherd on a mountain, and watching his goats took up all his time, he said.

Taj didn’t believe that he’d been sold to the U.S. military by bounty hunters or political opponents. The real reason he was arrested and brought to Guantánamo, he said, was simple: he had a temper.

He told us his story. The houses in his village didn’t have access to running water, and the U.S. military was trying to help out. His cousin, Ismael, was employed by the Americans and was responsible for setting up the waterlines.

“He gave every house in the village a water pipe, except mine,” Taj said.

It was Ramadan, the month of fasting, and he had just returned from a short trip out of town. When his mother told him what had happened, Taj went to confront his cousin, whom he found smoking a cigarette. When he inquired about the water, Ismael curtly told him to ask the Americans about it.

The two started arguing and soon began fighting.

“I got a stick, and I beat him over head,” Taj said. “His head started bleeding.” Villagers pulled the two men apart. Ismael shouted at his cousin, saying that he would have him reported to the Americans.

“He said he was going to make sure I was sent to Guantánamo,” Taj told us. “Everyone heard him.”

After the brawl, Taj walked home, not thinking much about Ismael’s threats. But four days later, a group of Americans with Afghan interpreters came to his house late at night and woke him up. They questioned him about attacking his cousin. Then, they searched his house, tied his hands, and took him to the nearby military base, where he was put in a room for the night.

“I slipped my hands out of the cuffs and went to sleep,” Taj said, smiling.

He figured Ismael would get over his anger and tell the U.S. soldiers to let him go the next day. When he woke up in the morning, he heard his cousin speaking with the Americans. He quickly slipped the cuffs back on and waited, expecting to be released.

Instead, he was taken to Bagram Air Force Base. From there, he was flown to Guantánamo. It was his first flight in an airplane.