My Guantanamo Diary (4 page)

Read My Guantanamo Diary Online

Authors: Mahvish Khan

Always respectful, Mousovi stood up from the white plastic lawn chair provided for him and waited quietly for the officers to begin the proceedings.

When he stood, the panel of officers glanced at each other and then back at the prisoner. Finally, the interpreter turned to him and explained that he should be seated. The chains rattled as he resumed his seat.

The tribunal president read the hearing instructions. Ali Shah indicated that he understood, then turned and faced the panel of military officers.

“Mr. President and respectable tribunal members, with utmost respect to all of you, I am delighted that after about one and a half years, I am for the first time witnessing a tribunal, which apparently looks like a court system,” he said nervously through the interpreter.

But this court, it appeared, wasn’t going to allow him to bring forth any witnesses. Because the United States doesn’t have diplomatic relations with Iran, there had been problems processing the request to find his witnesses there. The Afghan Embassy, meanwhile, had simply never responded to a request to locate the witnesses in Afghanistan. But the panel told him that one of the Guantánamo detainees would be allowed to testify on his behalf. The other would be allowed to submit something in writing.

Mousovi’s mind raced, he told me later. How could he prove his innocence without witnesses? He tried to persuade the panel that, at the very least, he needed the second Guantánamo detainee witness to be present to answer specific questions. This was a man from his hometown who could offer valuable evidence and testimony. “He was a security chief of Paktia province, so he knows about my case very well,” he pleaded.

But his requests were quickly denied. Seeing his disappointment, the tribunal president reassured him that this would not be held against him in any way.

The panel’s first accusation: “The detainee is associated with the Taliban and/or al-Qaeda.”

“Not only do I have nothing in common with the radical Taliban or extremist al-Qaeda, I am completely against their

ideology!” Mousovi responded. He had been a refugee in Iran during the entire Taliban rule, he said. He had refused to set foot in his country for even a day to tend to his personal property while the Taliban held his homeland hostage and looted his home and estates.

In Iran, Mousovi had been forced to work as a taxi driver, a tailor, and a tutor to feed his family. But he hadn’t even thought about taking his family back to Afghanistan.

“I am a Shiite Muslim,” he said, “and they looked at Shiites as infidels. As enemies. They butchered my people. The Shiites were an endangered minority with no political voice under the Taliban. If I had associations with them, why wouldn’t I have returned to my country?”

Far from associating with the Taliban, Mousovi insisted that he was a zealous supporter of Afghan democracy. After coalition forces ousted the Taliban, he returned to his country in April 2002 and worked with the United Nations to help increase support for a new democratic Afghanistan. In June of that year, he also attended the first

loya jirga

, an internationally backed assembly of leaders who met in Kabul to select Hamid Karzai as the country’s post-Taliban head of state.

But the military panel accused him of going to Afghanistan to funnel money to anticoalition insurgents.

“Please. Tell me, which money?” he asked. “This is imaginary, invisible and psychic money. I was in Gardez for just two days, so what happened with this money?”

The tribunal president said that the evidence concerning the money was classified. The panel proceeded to accuse Mousovi of distributing money, food, and Kalashnikov rifles to al-Qaeda fighters preparing to fight the United States, al-

legedly before the Taliban was defeated, even though Mousovi was in Iran at the time.

Finally, he was accused of fighting in the U.S.-backed war against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the 1980s. This was something that the United States had wanted and encouraged Afghans to do. Now, Mousovi was being forced to respond to this allegation as if it were a crime.

He didn’t deny his support of the mujahideen during their fight against the Russians. He had been a medic helping wounded resistance fighters. There were still bullet fragments lodged in the muscles of his neck, where he had been shot twenty-eight years before by a Russian soldier.

Mousovi had hoped for some clarity. He had hoped that the tribunal would see that there had been a mistake. Instead, his day in court left him confused.

“It’s still not clear to me what I am being charged with,” he said. “Is it my fault, or is it my sin, that I fought against the Russians? That I fought against communism? Or was it my sin that I didn’t associate with the Taliban? Or maybe it is my fault that after the establishment of democracy, I returned to my country to serve my people and help my people and our national security with the

loya jirga

? Or maybe it was my fault because my people love me and thought of me as a good servant.”

The panel sat in silence.

Mousovi spoke again. “By our friends and by our enemies we are punished,” he said. “The bullet, the Russian bullet is still in my neck. That is a gift from the Russians, and I consider Russia our enemy. These handcuffs and this uniform is a gift from our friends, from you.”

Finally, the tribunal president spoke. “Very well, thank you for your testimony,” he said. And that was all.

Mousovi went back to Camp Delta that afternoon. Several days later, he received notice that the military panel had declared him an enemy combatant.

Peter stepped out to speak with the guards, and the doctor leaned closer to me and asked about my family. He told me how happy it had made him to see me walk through the door.

“I had no idea that there were Pashtun girls like you in America,” he said with a laugh. I told him that I had no idea there were men like him at Guantánamo, that he was just like any member of my family, and that I was shocked to see him there.

It was amazing to me how quickly I’d come to feel comfortable in the presence of this man. It wasn’t hard to pinpoint why. He was articulate, just like my father, and extremely hospitable, like any of my uncles or aunts. He looked like them too and was immediately affectionate toward me. But I warmed up to him quickly also because he is probably one of the most gentle individuals I’ve ever met. Almost immediately, I knew he was good, someone I could relate easily to and trust.

He asked me what I was studying and said that my parents must be proud that I was in my final year of law school. We talked briefly about the life he missed. More than anyone, he missed his daughter, Hajar. His memory may have been impaired, but there was one moment with her that he remembered as though it had happened just the day before. Hajar had run to him in her ruffled dress and thrown her little arms around his neck, pulling his face down to hers. He’d lifted the eight-year-old onto his lap and asked what kind of gifts she wanted from Afghanistan. “She told me, ‘I want you to come back quickly, Baba-jaan,’” he recalled, and his voice broke.

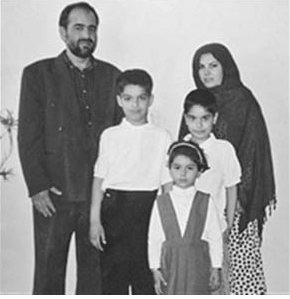

Ali Shah Mousovi, a.k.a. detainee No.

1154, with his family before his arrest.

Courtesy of Dr. Ali Shah’s family.

Mousovi fiddled with the label on the Coke bottle he was holding. When he looked up, I didn’t know what to say to him. I just sat there. Luckily, Peter came back into the room.

In his third year of detention, Mousovi looked for solace in God. Five times a day, he would perform his Muslim duties when he heard the prerecorded Arabic call to prayer played over camp loudspeakers.

Allahu Akbar

,

Allahu Akbar

—God is the Greatest, God is the “Greatest.

Hayya ‘ala-s-Salah, Hayya ‘ala-s-Salah

—Come to prayer, come to prayer.”

He would wash, align his prayer rug to the East, and stand shoulder to shoulder with a few of the other detainees in Camp 4. They would pray together and pray for one another.

The doctor interacted as much he could with the other prisoners. He preferred to be detained in predominantly Afghan blocks. Guantánamo has eight camps. Each is subdivided into several blocks with military-style alphabetical names: Alpha, Bravo, Charley, Delta, Echo, and so forth.

5

Detainees not in

solitary confinement are moved every few months so that they are never in one place long enough to form friendships with the prisoners in adjacent cages.

It was difficult for Mousovi when he was held for a time in a predominantly Arab block, where some of the Arabs, who looked down upon Afghans, treated him badly. It didn’t help that he didn’t speak Arabic.

But he also felt like an outsider among some of the other Afghans. Unlike him, many of his fellow prisoners were farmers, butchers, and laborers. Many of them had multiple wives and herds of children. Mousovi had been committed to the same woman since the day they met. He had only three children, not ten.

He tried to stay busy. He wrote poetry and kept a record of his experiences. Once a week, a soldier would push a book cart through the camp. But Mousovi and the other detainees were all tired of reading

Harry Potter

in Pashto. Some of the detainees were so bored that they tried memorizing it because it gave them something to do. The doctor told us that he wished he could keep up his studies and asked us to bring him a

Physicians’ Desk Reference

and give it to the military for clearing. We were sure, however, that the military would never allow such a book in the camp library for fear that some detainees would figure out how to create lethal concoctions of drugs to commit suicide.

So, Mousovi spent a lot of time with the one book he was allowed, the Qu’ran. American imprisonment would help him become a better Muslim. And he wrote letters home and read and reread the letters written to him and delivered by the International Red Cross. They were his only window onto what his life had once been.

A letter from Hajar:

May 10, 2006

I am sending the biggest and warmest greetings to my Baba-jaan—

sweet father.

I hope you are in good health and all right. We are all doing fine

here—other than longing for the presence of a badly missed kind

father. But I am certain that with the grace of God, we will have

you here again very soon. My dear sweet Baba, I miss you very

much. I hope and pray that your innocence is proven and that you

are released very soon.

Everyone is sending you their salaams and greetings. Abi-jaan,

sweet aunty and her family, Grandma, and everyone else sends

their love. Dear father, Abi-jaan is doing fine. She is taking her

medications and is waiting for you to come home.

Dear father, this year you missed my birthday again, but I hope

you will be here for Abu-Zar’s birthday so we can throw him a big

party.

Dearest sweet father, the space on this paper is running out, but

my words are always unfinished. I am hoping and praying to tell

you everything else I have to say, when I see you in person. Kind

sweet Baba—by the way Abi-jaan has a message for you too:

[along the edges of the page] Bachai-jaan—my dear child—

salaam. I am doing well. The kids are studying hard, and I am

with them. You are an innocent man without blame, and I am

waiting here for you.

Khuda hafiz

—May God’s peace be with you.

Well, Baba-jaan—sweet father—if I could, I would kiss your

gentle dear hands from far away.

Khuda hafiz

—May God’s Peace be with you.

With love from your daughter,

Hajar

[To be handed to my innocent father]