My Guantanamo Diary (7 page)

Read My Guantanamo Diary Online

Authors: Mahvish Khan

“Lying is against my religion,” he retorted. “I am very close to my grave at this age. I will not lie to you in any matter.”

The panel accused Nusrat of supporting a terrorist organization in Afghanistan called Hezb-Islami-Gulbadin (HIG), which is alleged to have ties to Osama bin Laden. He was also accused of possessing a cache of weapons.

Izatullah, who testified as a witness at the hearing, maintained that the weapons were in a storehouse set up by the Afghan defense ministry that he had been paid to guard and maintain. The ten-year Soviet occupation of Afghanistan had

left behind large amounts of uncollected heavy armaments, Izatullah explained. Following the ouster of the Russians, tribal feuds and civil strife were rampant. After the Taliban fell, the United Nations launched the Afghanistan New Beginnings Program to help President Hamid Karzai’s defense ministry implement nationwide disarmament. Under this arms collection program, weapons were gathered from the people and placed in warehouses for storage. It was one of these storehouses that the Karzai government paid him to guard, Izatullah insisted.

Nusrat swore by Allah and “my gray beard” that this was the truth. If anyone could prove otherwise, he said, “I will allow you to sacrifice all of my children.”

The panel, apparently unimpressed, read off another charge: Nusrat was “a primary coordinator” for the HIG in Sarobi, and the HIG leadership had plotted to kidnap coalition force members and use them as hostages to be exchanged for Nusrat.

Nusrat demanded to face his accusers, but the panel informed him that their names were classified and could not be revealed.

The weapons cache was brought up again, and Nusrat went into a frustrated tirade. “Yes, I had these weapons in my possession, but I told you that they belonged to the Afghan government, and I had all the numbers,” he fumed. “To ensure the security of these weapons, the government of Afghanistan gave my son fifty men to guard the weapons, with salary and meals.”

“How can I be a

dushman jangee

—an enemy combatant?” Nusrat demanded, reminding the panel of his paralysis. Finally,

he insisted that it was the United States that had betrayed the Afghans.

“While we defeated the Russians, you didn’t help us,” he asserted. “You turned your backs on us and left. The people of Afghanistan are like your children. You don’t leave your children and turn away from them. You are our leaders.”

Nusrat insisted that all the accusations against him had probably been brought by some “shameless” Afghan enemy who had sold him to the Americans for a large bounty. He maintained that he and his family had fully supported the Americans and the Karzai administration and had hoped that the United States would bring peace and help rebuild his country.

While he languished in Guantánamo, he said, another son, Abdul Wahid, was fully embracing America’s democracy initiative in Afghanistan. The twenty-seven-year-old had been elected a parliamentary representative in the 2005 United Nations– backed National Assembly and Provincial Council elections, Afghanistan’s first democratic voting in decades.

Not long after his hearing, Nusrat was classified an enemy combatant.

Peter and I had brought the old man some lunch—pizza, pistachios, baklava. He was grateful, but he was tired of the bland American way of cooking. He wanted meat or fish. He asked us to bring him something with spices. I promised to make him some

kabali pillau

, a popular rice-and-lamb dish, and lamb chops if he was still there when we came back.

I cracked open some pistachios and handed them to him as we discussed his case. He took a few sips of the chai and told me that he preferred his tea with crushed

lachi

, or cardamom.

Every now and then, he would look at me and say, “

Bachai

, you should come spend time in the mountains of Afghanistan so your Pashto dialect improves.”

This quickly became a running joke between us. Sometimes he would get frustrated with me for not knowing enough about the history of Afghanistan.

“What kind of Pashtun girl are you? How can you not know about Bacha Khan; he was the leader of the Pash-tuns,” he snapped, raising his bushy gray eyebrows. “You need to spend time in Afghanistan with my family. We will fix you.”

He grinned broadly when I promised to visit Afghanistan as soon as he was released.

Some off-duty guards at the Clipper Club told me their pet name for Nusrat: they called him “Speedy” because he hobbled at such a snail’s pace with his walker.

When Peter asked him about his health, it opened a Pandora’s box.

Nusrat had become very ill two years earlier, while in Camp 4. His legs started deteriorating badly, and although a military doctor treated him, the elderly man was not satisfied with his medical care.

“He gave me just six pills, and I asked for more,” he said. “They never give enough medicine to heal, only enough so I

don’t die,” he said. “They diagnose your problem but never make it better.”

He also had digestive problems and complained of constant swelling in his legs. He was given pain killers, but the medicine upset his stomach, so he only took it when he couldn’t stand the pain.

As Peter took notes and asked questions about his hearings, the elderly man extended his trembling hands, offering us some of the pistachios and almonds we had brought for him.

As the meeting wound down, Nusrat seemed tired. We couldn’t engage him on legal issues. He asked why no journalists had been allowed to come to Guantánamo. He wanted the world to know his story. Then, he asked me what I was studying in school. When I said I was in my last year of law school, he smiled and nodded.

“

Inshallah—God willing—you will be a lawyer,” he said.

Then, he asked about my marital status. When I told him I was single, he seemed to find it incomprehensible. “

Bachai

, why aren’t you married? Don’t ruin yourself,” he said. I smiled when he said that. While my parents rarely pushed the issue, it was something I was familiar with. There’s a preoccupation with marriage in the East, particularly in rural areas and particularly for girls, whose social and economic well-being is linked to finding a husband. Most Afghan women don’t work, and marriage is their only ticket to a life outside of their father’s home. They marry very young too—sometimes in their mid-teens. So, as I was in my late twenties, Haji Nusrat likely thought I was an old maid and worried that I was destined for a childless life of celibacy.

Peter turned the subject to filing petitions and the length of time court proceedings might take. Nusrat’s mood changed

again, this time to one of despair. He stopped eating pistachios and gazed at Peter’s face as he spoke.

“Allah has made you a very handsome man,” he said to Peter. “You are also a great man. May Allah make you even greater.” Then, he promised he’d make Peter a famous lawyer and bring him endless business if he helped him get home. “Everyone in Afghanistan will know your name,” he pleaded. As I translated, I felt a lump growing in my throat. Suddenly, I couldn’t speak. Peter and Nusrat watched as the tears dripped onto my shawl.

The old man looked at me. “You are a daughter to me,” he said. “Think of me as a father and pray for me,

bachai

.” I nodded, aligning and realigning pistachio shells on the table as I translated.

As the meeting ended, it was obvious that the old man was in pain. His legs hurt, and he tried to stand and stretch them. He pushed hard against the tabletop with his palms, trying to lift his weight. I leapt to his side and helped him stand. He gripped the edge of the table for balance and exhaled deeply.

A few moments later, I helped him sit back down. As we started collecting our things to go, I turned back to Nusrat, who was watching us gather up the pizza boxes and pistachio shells and unfinished baklava. The military didn’t allow any food to be left with the detainee, so we had to take any leftovers with us.

“

Bachai

, tell your mother and your father that an old man with a white beard sends his salaams,” he said.

I responded with the customary reply: “

Walaikum as-salaam

—And may peace also be upon you.”

I adjusted my shawl one last time and glanced at him. He was quiet for a moment. Then, he opened his heavy arms to

me, and I embraced him. He pushed my head into his white prison uniform and for several moments prayed for me as Peter watched:

“

Inshallah—God willing—you will find a home that makes you happy. Inshallah

,

you will be a mother one day. Inshallah

,

you will always have a family that will protect you. Inshallah

,

you will finish law school and continue to help us. Inshallah

,

you will make the world proud.”

Then, he patted my back. “You are a great woman, and may Allah make you greater,” he said.

Finally, he let me go and asked me to say

du’a

—prayers— for him.

“Of course,” I promised. “Every day.”

And until the next time I saw him, I did.

BIG BOUNTIES

Before I got involved with Guantánamo, I had no opinion about whether the detainees there were guilty or innocent; I just thought they all deserved a fair hearing and due process. But after I met some and talked to them, and after I read their files, I came to believe that many, perhaps even most, were, as Tom Wilner had put it, innocent men who’d been swept up by mistake.

I really became convinced when I found out about the bounties.

Many of the men I met insisted that they’d been sold to the United States. During the war after September 11, the U.S. military air-dropped thousands of leaflets across Afghanistan, promising between $5,000 and $25,000 to anyone who would turn in members of the Taliban and al-Qaeda. Considering that the per capita income in Afghanistan in 2006 was $300, or 82 cents a day, that’s like hitting the jackpot. The median

income for each American household was $26,036 in 2006.

1

If a bounty system of equal proportions were offered to Americans, it would be worth $2.17 million. The average American and the average Afghan would have to work for eighty-three years to make that kind of money. One particularly disingenuous leaflet offered Afghan locals up to a whopping $5 million.

Of course, offering large sums as bounty doesn’t violate any international laws. But when the result is a pattern of hundreds of men being randomly sold into captivity and then held without due process on the basis of flimsy allegations made by people who benefited financially, it’s at the very least cause for concern—and a second look.

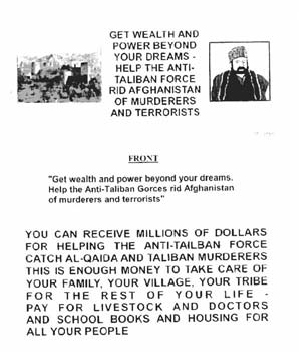

The Department of Defense (DOD) has said it was unaware of any sort of bounty being paid for prisoners. Here are two of the leaflets:

Bounty leaflet 1 in English.

Bounty leaflet 2, front and

backside, in Pashto and Dari.

(English translation: Up to $5

million will be awarded for

providing information about the

whereabouts and/or capture of

Taliban and al-Qaeda leaders.)

Then defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld told reporters in late 2001 that leaflets were dropping across Afghanistan “like snowflakes in December in Chicago.”

Afghanistan has been a country of deep-seated, relentless conflict for generations. Here, in the United States, with our rule of law and live-and-let-live traditions, we can’t understand the complex animosities, based on tribal affiliation and religious, ideological, and political differences, that might lead one Afghan to turn another in. Territorial feuds over land are common. Throw large monetary rewards into the mix, and the result could easily be a lot of false reports—and wrongful detentions.

Afghan warlords and locals went for the bait. But they weren’t the only ones. The hefty bounties also created an extensive black market for abductions in Pakistan. That’s where many detainees’ road to Guantánamo began—specifically with Pakistan’s notoriously unscrupulous Inter-Services Intelligence.

When the United States began bombing in late 2001, thousands of Afghans fled to neighboring Pakistan. The Pakistani police, border guards, and locals, all eager to get their hands on large sums of cash, seized hundreds of men. It was big business. Pakistani president Pervez Musharraf even bragged about it in his memoir,

In the Line of Fire

.

“We have earned bounties totaling millions of dollars,” he wrote, admitting that his agents had handed over 369 men to the U.S. military in exchange for Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) “prize money.” When he got a lot of flak for his published admissions, Musharraf quickly backtracked. Subsequent editions of his book have dropped this mention of the 369 men and CIA prize money.

According to Amnesty International reports, two-thirds of the men who landed in Guantánamo were picked up in

Pakistan, where many were “groomed” in local jails to grow out their beards and look more like Taliban before being sold to the U.S. military.

Arabs in particular became a valuable commodity and an opportunity for profit. They stood out and were easily rounded up. Tom Wilner told me that none of the Kuwaitis at Guantánamo had been captured on any battlefield; they weren’t even accused of engaging in any hostilities against the United States. His clients told him that they had been sold by Pakistanis or Afghan warlords.

Several Chinese Muslim detainees, known as Uighurs, told their attorney, Sabin Willett of Bingham and McCutchen, that they had been betrayed by Pakistanis. They had gone to Afghanistan for military training so that they could fight for independence from China. When U.S. warplanes started bombing Afghanistan, they, along with many others, fled to the Pakistani border, where locals welcomed them.

“They killed a sheep and cooked the meat and we ate,” Adel Abdul-Hakim told Willett. Then, that night, Hakim said, they were driven to a local prison and, from there, handed over to the U.S. military.

Theoretically, a bounty program for terrorism suspects could be effective—if there were an actual investigation to determine who was al-Qaeda and who had been swept up inadvertently. But the U.S. military conducted no investigations.

“America is a strong, powerful country,” Haji Nusrat Khan told me. “I know that my own people turned me in for money, but the Americans can find anything out. They should have investigated these wrongly made accusations about me.”

I don’t believe that the military arrested and detained innocent men maliciously. I know that September 11 sparked great fear and that the military is charged with protecting U.S. national security. But in pursuit of that goal, the U.S. government abandoned the most fundamental legal principles and failed to conduct the most basic inquiries. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis once said that the most insidious threats to liberty come from well-meaning people of zeal who act without understanding. There was a lot of zeal after September 11. In keeping Guantánamo Bay in operation, the DOD has dismissed the notion that innocent men may have been sold and brought there. Rumsfeld called the Guantánamo detainees there “the worst of the worst.” White House officials echoed his sentiments and said that the detainees had been trained to lie based on al-Qaeda manuals.

But in response to an Associated Press lawsuit brought in March 2006 under the Freedom of Information Act, the Pentagon was forced to declassify information pertaining to the detainees. The numbers tell another story. A statistical analysis of DOD documents relating to 517 current and former Guantánamo detainees shows that only 5 percent of the detainees had been captured as a result of U.S. intelligence work. The report, by Seton Hall law professor Mark Denbeaux and his son, attorney Joshua Denbeaux, also shows that 86 percent of the prisoners at Guantánamo were captured not by American forces but by Pakistani police and Afghan warlords at a time when the U.S. military was passing out cash rewards for turning over al-Qaeda and Taliban suspects.

Some of the detainees were accused and seized because they owned a Kalashnikov. That’s actually fairly common in

Afghanistan. The report also found that detainees were commonly held because they stayed at guesthouses in Afghanistan or wore Casio watches, which were thought to be used by al-Qaeda to detonate bombs.

Afghan detainee Abdul Matin was a science teacher who was arrested wearing a Casio watch. Matin thought someone was having a good laugh as they wrote up reasons to hold him. At his combatant status review tribunal, the military asked him to explain his “possession of the infamous Casio watch.”

Matin admitted that he had one—just as women, children, and old men in Afghanistan and elsewhere do. But he argued that wearing an ordinary black plastic watch didn’t make him a terrorist. Many of the guards at Guantánamo wore the same watch.

The Denbeaux study concluded that the vast majority of detainees aren’t connected to al-Qaeda, and most aren’t even accused of engaging in hostilities against the United States. When I read it, I thought about many of the men I had met. No doubt there are some terrorists at Gitmo. But it’s just as likely that there are good and innocent people. They’ve all been swept together without due process. Because there were no investigations, most of Guantánamo’s men are being held in a stateless black hole, an eerie Neverland where American laws and justice don’t exist. They’ve been presumed guilty without having a fair shot at proving their innocence. They’re numbered and kept away from journalists, while the Bush administration touts them collectively to the media as treacherous monsters and bomb makers.

I’ve encountered a few individuals who believe that, given the political climate, this is not the time to adhere to legal principles. We’re engaged in a war on terrorism, and the United States has been threatened by an unconventional enemy. For these reasons, they say, constitutional laws shouldn’t apply to Guantánamo detainees.

But the idea that due process and fair hearings go out the window when we are afraid of something or feel threatened erodes the essence of constitutional safeguards. Yet, such an erosion has stained U.S. history before. In times of war, threats to national security become the basis for abandoning the cornerstone principles enshrined in our constitution.

During World War II, which generated its share of fear and hysteria, more than one hundred thousand Japanese Americans suspected of espionage were taken from their homes, fired from their jobs, and detained in what President Franklin Roosevelt then called concentration camps. Not a single Japanese American was ever charged with or convicted of spying or committing any act of hostility toward the United States.

When Japanese American Fred Korematsu refused to relocate to one of Roosevelt’s detention centers, he was arrested by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and subsequently convicted in federal court. In

Korematsu v. United States

, Kore-matsu took his case challenging the legality of the president’s wartime policy to the Supreme Court. In a sharply divided 6–3 decision, the Court upheld Korematsu’s conviction in late 1944. The majority opinion, written by Justice Hugo Black, rejected Korematsu’s discrimination argument and upheld the government’s right to put Japanese American citizens

in detention camps due to the wartime emergency. The Court’s reasoning echoes the rhetoric the Bush administration uses to justify its actions today: We are at war with an enemy who threatens our national security.