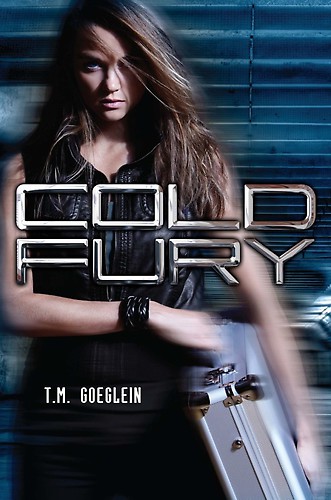

Cold Fury

Authors: T. M. Goeglein

Tags: #General, #Juvenile Fiction, #Action & Adventure, #Law & Crime, #Love & Romance

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

A division of Penguin Young Readers Group.

Published by The Penguin Group.

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.).

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England.

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd.).

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd).

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi—110 017, India.

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd).

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa.

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England.

Copyright © 2012 by T. M. Goeglein. All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, a division of Penguin Young Readers Group, 345 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

G. P. Putnam’s Sons, Reg. U.S. Pat. & Tm. Off. The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 978-1-101-57193-4

For Laura, who always has my back.

Contents

PRELUDE

MY NAME IS SARA JANE RISPOLI.

Several short weeks ago, I turned sixteen.

So far there has been nothing sweet about it.

I have braces, the thick, transparent type—they make my teeth appear too large for my mouth and my lips too small to contain them.

I have good hair and acceptable skin but my nose is Roman, as in it’s roamin’ all over my face, and I plan to do something about it someday.

I have a learner’s permit but no license, but I’ve been driving my dad’s old Lincoln Continental since I was thirteen, so big freaking deal.

I have a boyfriend—well, a boy who treats me like a friend instead of how I want to be treated, so BFD again.

I also have a steel briefcase, and inside that briefcase is ninety-six thousand dollars in cash, an AmEx Black Card in my name, a Sig Sauer .45 conceal-and-carry, and an old leather notebook stuffed full of so many unusual facts, indecipherable notes, and unlisted phone numbers that it’s held together with masking tape and rubber bands.

The notebook is why I have the gun.

What I don’t have anymore are my parents or little brother.

They’re either dead and gone, or just dead, or just gone.

I don’t have a Friendbook page.

I don’t have space on ISpace.

I threw my cell phone into Lake Michigan weeks ago.

I’m being watched, stalked, tapped, and spied on, and if the opportunity arises, the watchers and stalkers will try to snatch me, and the tappers and spies will try to kill me.

As long as I keep moving, I should be okay.

As long as I keep the notebook with me, I should stay alive.

This is not what I thought life would be like when I turned sweet sixteen.

1

A REQUIREMENT OF STUDENTS

at Casimir Fepinsky Preparatory (Fep Prep, as everyone calls it) is to keep a journal of their high school career.

I just reread the first two pages of mine, and so far it’s a doozy.

After all, how many sophomores can record their lives as a fugitive-slash-vigilante?

The truth, though, is that I wouldn’t keep a journal if I didn’t have to. I’m not naturally compelled to share the details of my life. That’s why blogging seems self-centered and tweeting is just, I don’t know, borderline insane. Does the world really care that I just ate an onion bagel and now I’m laughing out loud about it? Isn’t that something a crazy person would say?

Then again, I keep up with it partly because writing everything down helps me stay sane.

The other, more important reason is that it may help me find my family.

My English lit teacher, Ms. Ishikawa, is one of my favorites. She’s wise and tiny, like an energetic hamster wearing glasses. In guiding our journal writing, she quoted William Shakespeare’s

The Tempest

, saying, “What’s past is prologue”—the present is constructed from the events that preceded it.

That’s why I’ve decided to mine the past for information and use this journal as a storehouse—the place where I put the facts in order right up to the moment my family vanished.

The bloody, broken night marked the beginning of a quest—to find them and to discover who and what we really are. To do that requires patience and concentration, but it also requires context, of which I have very little. Tracking them down without knowing what occurred before that night is as impossible as trying to put a puzzle together with pieces missing—you look at jigsaw fragments and see a pair of piercing blue eyes but no head, and a hand but no arm, and the intelligent smile of a young boy but no boy. No dad, no mom, no little brother. Only chunks and shards that don’t fit, since, as Ms. Ishikawa and Shakespeare taught, a human life is not made up only of the present. It’s constructed from dead slices of time, fading memories, and long-ago whispered conversations. So now I’m examining times gone by like a forensic pathologist, dissecting it for clues about my home torn apart and family ripped free of the living world.

The terrible thing that happened to them didn’t occur in a void.

It wasn’t a wayward meteor or supernatural act that destroyed our lives and put me on the run.

It occurred because other terrible things happened before it. I’m determined to understand what they were, and the best way to do it is by taking a hard, honest look at my family.

• • •

My grandfather, my dad’s dad, was Enzo Rispoli, a tiny, soft-spoken man who was in charge of the family business, Rispoli & Sons Fancy Pastries. Grandpa had many nicknames. “Enzo the Baker,” which was self-explanatory, and “Enzo the Biscotto,” which was my favorite since

biscotto

is Italian for “little cookie,” and that’s what he reminded me of—a small, sweet pastry. Now and then, some men who spoke in such low tones that only my grandpa could hear them (or as I thought of them, the “Men Who Mumbled”) would call him “Enzo the Boss,” which was confusing, since the only people he ever bossed around—gently—were my father, Antonio, whom everyone calls Anthony, and his younger brother Benito, whom everyone calls Buddy.

I really do despise Uncle Buddy.

Funny, because I used to adore him.

I can’t deny that my uncle was my best buddy, and my parents’ too—or so it seemed. Uncle Buddy was always around since, to be honest, he didn’t have much of a life of his own. There’s a word I hear in old movies now and then—

schlub

—that fits him perfectly. He was short and blocky where my dad is tall and thin, shambling and awkward where my dad is graceful and funny, and he laughed too loud at inappropriate moments. Uncle Buddy ate like a garbage truck, shoveling pasta and spattering his shirt with red sauce, and smoking was a constant habit, with him puffing on our porch in an intense, desperate way, like he was mad at the cigarettes. Besides my family, he was alone most of the time, with no real friends and no girlfriend ever. In general, my family tends to stick close and socialize mainly among one another, but Uncle Buddy was extreme. He oozed loneliness, but an annoying type of loneliness, like he wanted something in particular more than he wanted just to be wanted.

There’s an old familiar story my parents tell—they take turns telling it—about how they met. My mom was working in a department store as a hand model, displaying diamond rings, when my dad noticed her. Very smoothly, he asked to see a ring, inspected it, and then, as he slipped it back on her finger, said, “Will you marry me?” Months later, he took her to Italy to pop the question for real and had a ring made for her there, in a little hilltop village called Ravello. It’s a gold signet ring with an

R

raised in tiny, hard, winking diamonds, and at the end of the story she always turns it on her lovely finger and confesses that she would have said yes the first time my dad asked if he hadn’t been so full of self-confidence.

Uncle Buddy loved that story a little too much.

I know now that he was viciously jealous of who my dad was and what he had, but hid it beneath a thin layer of false good nature.

He pretended to love us, too, but actually despised us, and buried that as well.

He spent hours telling my mom jokes in the kitchen, making her laugh while she used her delicate thumbs and forefingers to shape delicious little ravioli, and helped my dad reattach the lightning-struck weather vane to the slate roof of our big old house on Balmoral Avenue. My uncle happily packed me into his rusty red convertible and took me wherever I wanted to go—Foster Beach or the Art Institute or even shopping on Michigan Avenue, which bored him senseless. On warm summer weekends, we all rode the El to Wrigley Field and sat in the bleacher seats Uncle Buddy had bought especially so we could cheer on his favorite Cubs center fielder, Dominic Hughes.

In particular, I remember breakfast at Lou Mitchell’s.

It was Uncle Buddy’s favorite diner in Chicago.

He loved everything about the place, from its neon sign on the outside to its snug booths on the inside. It was in one of them, with him and me sitting side by side sharing blueberry pancakes so big they spilled over the plate, and my mom and dad across from us sharing a secret smile, that she told us she was pregnant and that it was a boy. I remember how my dad, tall and thinly muscular (like me) with a perpetual five o’clock shadow (not like me, thankfully), was grinning widely as he put his arm around my mom and pulled her close. I also recall the look on my mom’s face. She’s gorgeous, with green, almond-shaped eyes, high cheekbones (got ’em—thanks, Mom), and wavy black hair, and she literally seemed to be glowing. I was just a kid, confused and excited at the same time, so maybe I don’t remember correctly what happened next, but I think I do.