More Guns Less Crime (31 page)

Read More Guns Less Crime Online

Authors: John R. Lott Jr

Tags: #gun control; second amendment; guns; crime; violence

neighboring state adopts a

one-gun-a-month rule

•The result is significant at the 1 percent level for a two-tailed t-test. The result is significant at the 5 percent level for a two-tailed t-test. c The result is significant at the 10 percent level for a two-tailed t-test. d The result is significant at the 12 percent level for a two-tailed t-test. *The F-test is significant at the 1 percent level. **The F-test is significant at the 5 percent level. ***The F-test is significant at the 10 percent level.

The evidence for the before-and-after average crime rates for the different types of policing policies is more mixed, and my research does not attempt to deal with issues of why the different rules were adopted to begin with. 32 In ten cases, the policing policies produce significant reductions in crime, but in six cases there are significant increases in crime. Including cases that are not statistically significant still produces no consistent pattern: the policing policies are associated with declines in crime in fifteen cases and increases in twelve cases. A possible explanation for such results might be that adopting new policing policies reallocates resources within the police department, causing some crime rates to go down while others go up. Indeed, each of the three policing policies is associated with increases in some categories of crime and decreases in others. It is difficult to pick out many patterns, but community policing reduces violent crimes at the expense of increased property crimes.

Revisiting Multiple-Victim Public Shootings

Student eyewitnesses and shooting victims of the Pearl High School (Mississippi) rampage used phrases like "unreal" and "like a horror movie" as they testified Wednesday about seeing Luke Woodham methodically point his deer rifle at them and pull the trigger at least six times.... The day's most vivid testimony came from a gutsy hero of the day. Assistant principal Joel Myrick heard the initial shot and watched Woodham choosing his victims. When Woodham appeared headed for a science wing where early classes were already under way, Myrick ran for his pickup and grabbed his .45-caliber pistol. He rounded the school building in time to see Woodham leaving the school and getting into his mother's white Chevy Corsica. He watched its back tires smoke from Woodham's failure to remove the parking brake. Then he ordered him to stop. "I had my pistol's sights on him. I could see the whites of his knuckles" on the steering wheel, Myrick said. He reached into the car and opened the driver-side door, then ordered Woodham to lie on the ground. "I put my foot on his back area and pointed my pistol at him," Myrick testified. 33

Multiple-victim public shootings were not a central issue in the gun debate when I originally finished writing this book in the spring of 1997. My results on multiple-victim public shootings, presented in chapter 5, were obtained long before the first public school attacks occurred in October 1997. Since that time, two of the eight public school shootings (Pearl, Mississippi, and Edinboro, Pennsylvania) were stopped only when citizens with guns interceded. 34 In the Pearl, Missis-

sippi, case, Myrick stopped the killer from proceeding to the nearby junior high school and continuing his attack there. These two cases also involved the fewest people harmed in any of the attacks. The armed citizens managed to stop the attackers well before the police even had arrived at the scene—4!£ minutes before in the Pearl, Mississippi, case and 11 minutes before in Edinboro.

In a third instance, at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, an armed guard was able to delay the attackers and allow many students to escape the building, even though he was assigned to the school because he had failed to pass his shooting proficiency test. The use of homemade grenades, however, prevented the guard from fighting longer. There is some irony in Dylan Klebold, one of the two killers, strongly opposing the proposed right-to-carry law that was being considered in Colorado at the time of the massacre. 35 In the attack on the Jewish community center in Los Angeles in which five people were wounded, the attacker had apparently "scouted three of the West Coast's most prominent Jewish institutions—the Museum of Tolerance, the Skirball Cultural Center and the University of Judaism—but found security too tight." 36

It is remarkable how little public discussion there has been on the topic of allowing people to defend themselves. It has only been since 1995 that we have had a federal law banning guns by people other than police within one thousand feet of a school. 37

Together with my colleague William Landes, I compiled data on all the multiple-victim public shootings occurring in the United States from 1977 to 1995, during which time fourteen states adopted right-to-carry laws. As with earlier numbers reported in this book, the incidents we considered were cases with at least two people killed or injured in a public place. We excluded gang wars or shootings that were by-products of another crime, such as robbery. The United States averaged twenty-one such shootings annually, with an average of 1.8 people killed and 2.7 wounded in each incident.

What can stop these attacks? We examined a range of different gun laws, including waiting periods, as well the frequency and level of punishment. However, while arrest and conviction rates, prison sentences, and the death penalty reduce murders generally, they have no significant effect on public shootings. There is a simple reason for this: Those who commit these crimes usually die in the attack. They are killed in the attack or, as in the Colorado shooting, they commit suicide. The normal penalties simply do not apply.

In the deranged minds of the attackers, their goal is to kill and injure as many people as possible. Some appear to do it for the publicity, which

0.06

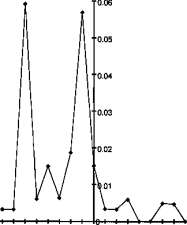

-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1012345678 Years before and after adoption of right-to-carry law

Figure 9.14. Murders from multiple-victim public shootings per 100,000 people: data from 1977 to 1995

is related to the harm inflicted. Some may do it only because they value harming others. The best way to prevent these attacks might therefore be to limit the carnage they can cause if they do attack. We find only one policy that effectively accomplishes this: the passage of right-to-carry laws.

When different states passed right-to-carry laws during the nineteen years we studied, the number of multiple-victim public shootings declined by a whopping 84 percent. Deaths from all these shootings plummeted by 90 percent, and injuries by 82 percent. Figure 9.14 demonstrates how the raw number of attacks changes before and after the passage of right-to-carry laws. The extensive research that we have done indicates that these results hold up very well when the long list of factors discussed in this book is taken into account. The very few attacks that still occur in states after enactment of right-to-carry laws tend to occur in particular places where concealed handguns are forbidden, such as schools.

The reason why the deterrent effect on multiple-victim public attacks is greater than on attacks on individual victims is fairly straightforward. Say the probability that a victim has a permitted concealed handgun is 5 percent. That will raise the expected costs to the criminal and produce some deterrence. Yet if one hundred adults are present on a train or in a restaurant, even if the probability that any one of them will be able to

offer a defense is only 5 percent, the probability that at least someone there has a permitted concealed handgun is near 100 percent. 38 The results for multiple-victim public shootings are consistent with the central findings of this book: as the probability that victims are going to be able to defend themselves increases, the level of deterrence increases.

Concealed-handgun laws also have an important advantage over uniformed police, for would-be attackers can aim their initial assault at a single officer, or alternatively wait until he leaves the area. With concealed carrying by ordinary citizens, it is not known who is armed until the criminal actually attacks. Concealed-handgun laws might therefore also require fewer people carrying weapons. Some school systems (such as Baltimore) have recognized this problem and made nonuniformed police officers "part of the faculty at each school." 39

Despite all the debate about criminals behaving irrationally, reducing their ability to accomplish their warped goals reduces their willingness to attack. Yet even if mass murder is the only goal, the possibility of a law-abiding citizen carrying a concealed handgun in a restaurant or on a train is apparently enough to convince many would-be killers that they will not be successful. Unfortunately, without concealed carry, ordinary citizens are sitting ducks, waiting to be victimized.

Other Gun-Control Laws

"Gun control? It's the best thing you can do for crooks and gangsters," Gravano said. "I want you to have nothing. If I'm a bad guy, I'm always gonna have a gun. Safety locks? You will pull the trigger with a lock on, and I'll pull the trigger. We'll see who wins." 40

Sammy "the Bull" Gravano, the Mafia turncoat, when asked about gun control

The last year has seen a big push for new gun-control laws. Unfortunately, the discussion focuses on only the possible benefits and ignores any costs. Waiting periods may allow for a "cooling-off period," but they may also make it difficult for people to obtain a gun quickly for self-defense. Gun locks may prevent accidental gun deaths involving young children, but they may also make it difficult for people to use a gun quickly for self-defense. 41 The exaggerated stories about accidental gun deaths, particularly those involving young children, might scare people into not owning guns for protection, even though guns offer by far the most effective means of defending oneself and one's family.

Some laws, such as the Brady law, may prevent some criminals from buying guns through legal channels, such as regular gun stores. Never-

theless, such laws are not going to prevent criminals from obtaining guns through other means, including theft. Just as the government has had difficulty in stopping gangs from getting drugs to sell, it is dubious that the government would succeed in stopping criminals from acquiring guns to defend their drug turf.

Similar points can be made about one-gun-a-month rules. The cost that they impose upon the law abiding may be small. Yet there is still a security issue here: someone being threatened might immediately want to store guns at several places so that one is always easily within reach. The one-gun-a-month rule makes that impossible. Besides this issue, the rule is primarily an inconvenience for those who buy guns as gifts or who want to take their families hunting.

The enactment dates for the safe-storage laws and one-gun-a-month rules are shown in table 9.5/ 12 For the implementation dates of safe-storage laws, I relied primarily on an article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, though this contained only laws passed up

Table 9.5 Enactment dates of other gun control laws

State Date law went into effect*

Safe-storage laws: a

Florida 10/1/89

Iowa 4/5/90

Connecticut 10/1/90

Nevada 10/1/91

California 1/1/92

New Jersey 1/17/92

Wisconsin 4/16/92

Hawaii 6/29/92

Virginia 7/1/92

Maryland 10/1/92

Minnesota 8/1/93

North Carolina 12/1/93

Delaware 10/1/94

Rhode Island 9/15/95

Texas 1/1/96 One-gun-a-month laws: b

South Carolina 1976

Virginia 7/93

Maryland 10/1/96

"Source for the dates of enactment of safe-storage laws through the end of 1993 is Peter Cummings,

David C. Grossman, Frederick P. Rivara, and Thomas D. Koepsell, "State Gun Safe Storage Laws

and Child Mortality Due to Firearms," Journal ofthe American Medical Association, 278 (October 1, 1997):

1084-86. The other dates were obtained from the Handgun Control Web site at http://www.hand-

guncontrol.org/caplaws.htm.

b Data were obtained through a Nexis/Lexis search. Lynn Waltz, "Virginia Law Cuts Gun Pipeline to

Capital's Criminals, Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, September 8, 1996, p. A7.

EPILOGUE/ 199

through the end of 1993. 43 Handgun Control's Web site provided information on the three states that passed laws after this date. The laws share certain common features, such as making it a crime to store firearms in a way that a reasonable person would know allows a child to gain use of a weapon. The primary differences involve exactly what penalties are imposed and the age at which a child's access becomes allowed. While Connecticut, California, and Florida classify such violations as felonies, other states classify them as misdemeanors. The age at which children's access is permitted also varies across states, ranging from twelve in Virginia to eighteen in North Carolina and Delaware. Most state rules protect owners from liability if firearms are stored in a locked box, secured with a trigger lock, or obtained through unlawful entry.

The state-level estimates are shown in table 9.6. Only the right-to-carry laws are associated with significant reductions in crime rates. Among the violent-crime categories, the Brady law is only significantly related to rape, which increased by 3.6 percent after the law passed. (While the coefficients indicate that the law resulted in more murders and robberies but fewer aggravated assaults and as a consequence fewer overall violent crimes, none of those effects are even close to being statistically significant.) Only the impact of the Brady law on rape rates is consistent with the earlier results that we found for the data up through 1994.