More Guns Less Crime (34 page)

Read More Guns Less Crime Online

Authors: John R. Lott Jr

Tags: #gun control; second amendment; guns; crime; violence

The timing of changes in right-to-carry laws also makes their argument less plausible. Ayres and Donohue do not explain why the local changes in the cocaine market just happen to coincide with the passage

of right-to-carry laws, which have occurred at very different times in different states.

Other points are relevant to this issue. While the violent-crime rates fell across the entire state, the biggest drops occurred in the most crime-prone, heavily urbanized areas. Even if states that tend to adopt right-to-carry laws also "tend to be Republican and have high NRA membership and low crime rates" and thus to be less typical of the states where crack is a problem, there still exist high-crime counties within the state that do not fit the overall state profile. Indeed, it is those densely populated, high-crime counties that experience the biggest drops in violent crime. Finally, using the data up through 1996 produces similar results. Since so many states adopted right-to-carry laws at different times during the 1990s, it is not clear how cocaine or crack can account for the particular pattern claimed by Ayres and Donohue. Indeed, if anything, since the use of cocaine appears to have gradually spread to more rural states over time and subsided in areas where it had originally been a problem, the differences in trend that they are concerned about may have even been the reverse of what they conjecture.

5 Do right-to-carry laws significantly reduce the robbery rate?

Was there substitution from violent crime to property crime? Lott found

that the laws were associated with an increase in property crime Lott

argues that this change occurred because criminals respond to the threat of being shot while committing such crimes as robbery by choosing to commit less risky crimes that involve minimal contact with the victim. Unfortunately for this argument, the law was not associated with a significant decrease in robberies. In fact, when data for 1993 and 1994 was included, it was associated with a small (not statistically significant) increase in robberies. The law was associated with a significant reduction in assaults, but there does not seem to be any reason why criminals might substitute auto theft for assault. (Tim Lambert, "Do More Guns Cause Less Crime?" from his posting on his Web site at the School of Computer Science and Engineering, University of New South Wales [http:// www.cse.unsw.EDU AU/ ~ lambert/guns/lott/])

Q. What's your take on John Lott's study and subsequent book that concludes concealed weapon laws lower the crime rate? (Lott's book is titled "More Guns, Less Crime," University of Chicago Press, 1998.)

A. His basic premise in his study is that these laws encourage private citizens to carry guns and therefore discourage criminal attacks, like homicides and rapes. Think for a second. Most murders and rapes occur in

216/CHAPTER NINE

homes. So where would you see the greatest impact if his premise were true? You would see it in armed robbery. But there's no effect on armed robbery. His study is flawed, but it's costing us enormous problems. People are citing it everywhere. (Quote in the St. Paul, Minnesota, newspaper the Pioneer Planet, August 3,1998, from an interview with Bob Walker, president of Handgun Control, Inc.)

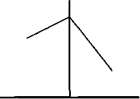

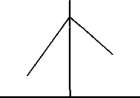

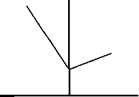

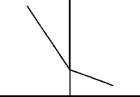

Both the preceding quotes and many other criticisms are based on not recognizing that a law can be associated with reduced crime even when the average crime rate in the period after the law is the same as or higher than the average crime rate before the law 87 For example, look at the four diagrams in figure 9.17. The first two diagrams show dramatic changes in crime rates from the law, but very different before-and-after average crime rates. In the first diagram (17a), the average crime rate after the law is lower than the average crime rate before it, while the reverse is true in the second diagram. The second diagram (lib) corresponds to an example in which the simple variable measuring the average effect from the law would have falsely indicated that the law actually "increased" the average crime rate, while in actual fact the crime rate was rising right up

Crime rate

Crime rate

Years before and after the adoption of the law Years before and after the adoption of the law a b

Crime rate

Crime rate

Years before and after the adoption of the law Years before and after the adoption of the law

c d

Figure 9.17. Why looking at only the before-and-after average crime rates is so misleading

EPILOGUE/217

until the law passed and falling thereafter. If I had another figure where the inverted V shape was perfectly symmetrical, the before-and-after averages would have been the same. (With this in mind, it would be useful to reexamine the earlier estimates for robbery shown in figures 4.8 and 7.4.)

The third diagram (17c) illustrates the importance of looking at more than simple before-and-after averages in another way. A simple variable measuring the before-and-after averages would indicate that the average crime rate "fell" after the law was adopted, yet once one graphs out the before-and-after trends it is clear that this average effect is quite misleading—the crime rate was falling until the law went into effect and rising thereafter. Finally, the fourth diagram (17d) shows a case in which the average crime rate is obviously lower after the law than beforehand but the drop is merely a continuation of an existing trend. Indeed, if anything, the rate of decline in crime rates appears to have slowed down after the law. Looking at the simple before-and-after averages provides a very misleading picture of the changing trends in crime rates.

6 Is the way criminals learn about victims ability to defend themselves inconsistent with the results?

Zimring and Hawkins observe that there are two potential transmission mechanisms by which potential criminals respond to the passage of a shall issue law. The first, which they term the announcement effect, changes the conduct of potential criminals because the publicity attendant to the enactment of the law makes them fear the prospect of encountering an armed victim. The second, which they call the crime hazard model, implies that potential criminals will respond to the actual increased risk they face from the increased arming of the citizenry. Lott adheres to the standard economist's view that the latter mechanism is the more important of the two—but he doesn't fully probe its implications. Recidivists and individuals closely tied to criminal enterprises are likely to learn more quickly than non-repeat criminals about the actual probability of encountering a concealed weapon in a particular situation. Therefore, we suspect that shall issue laws are more likely to deter recidivists.... Thus, if Lott's theory were true, we would also suspect that the proportion of crime committed by recidivists should be decreasing and that crime categories with higher proportions of recidivism—and robbery is likely in this category—should exhibit the highest reductions. Once again, though, the lack of a strong observed effect for robbery raises tensions between the theoretical predictions and Lott's evidence. (Ian Ayres and John J. Do-

nohue HI, "Nondiscretionary Concealed Weapons Laws: A Case Study of Statistics, Standards of Proof, and Public Policy," American Law and Economics Review 1, nos. 1-2 [Fall 1999]: 458-59)

I have always viewed both the mentioned mechanisms as plausible. Yet the question of emphasis is an empirical issue. Was there a once-and-for-all drop in violent crimes when the law passed? Did the drop in violent crimes increase over time as more people obtained permits? Or was there some combination of these two influences? The data strongly suggest that criminals respond more to the actual increased risk, rather than the announcement per se. Indeed, all the data support this conclusion: table 4.6, the before- and after-law time trends, the county-level permit data for Oregon and Pennsylvania, and the new results focusing on the predicted percentage of the population with permits. The deterrence effect is closely related to the percentage of the population with permits.

I have no problem with Ayres and Donohue's hypothesis that criminals who keep on committing a particular crime will learn the new risks faster than will criminals who only commit crimes occasionally. 88 However, that hypothesis will be difficult to evaluate, for data on the number and types of crimes committed by criminals are known to be notoriously suspect, as they come from surveys of criminals themselves. Some of the criminals appear to be bragging to surveyors and claim many thousands of crimes each year. But one thing is clear from these surveys: criminals often commit many different types of crimes, and hence it is generally incorrect to say that criminals only learn from one type of crime. In any case, even if Ayres and Donohue believe that robbers are more likely to learn from their crimes, the estimated deterrent effect on robbery turns out to be very large when the before-and-after trends are compared. 89

It is interesting that one set of critiques attacks me for allegedly assuming a once-and-for-all drop in crime from right-to-carry laws (see point 3 above), while at the same time I am attacked for assuming that the drop can be related only to the number of permits issued.

7 Have prominent "pro-gun " researchers questioned the findings in my hook?

To dispel the notion that Lott is simply being victimized by the "PC crowd," it may be helpful to mention the reaction of Gary Kleck, a Florida

State criminologist known for his generally "pro-gun" views Kleck

argues in his recent book that it is "more likely [that] the declines in crime coinciding with relaxation of carry laws were largely attributable to other factors not controlled in the Lott and Mustard analysis." (Jens Ludwig, "Guns and Numbers " Washington Monthly, June 1998, p. 51)

EPILOGUE/219

Even Gary Kleck, a researcher long praised by the NRA and identified as an authority on gun-violence prevention by Lott himself, has dismissed the findings. (Sarah Brady, "Q: Would New Requirements for Gun Buyers Save Lives? Yes: Stop Deadly, Unregulated Sales to Minors, at Gun Shows and on the Internet," Insight, June 21, 1999, p. 24)

The quote by Kleck has frequently been mentioned by Jim and Sarah Brady and other members of Handgun Control and the Violence Policy Center. 90 However, it is a rather selective reading of what he wrote. Their claim that Kleck "dismissed the findings" is hard to reconcile with Kleck's comment in the very same piece that my research "represents the most authoritative study" on these issues. 91