Moominvalley in November (10 page)

Read Moominvalley in November Online

Authors: Tove Jansson

Tags: #General, #Fantasy, #Action & Adventure, #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Family, #Classics, #Children's Stories; Swedish, #Friendship, #Seasons, #Concepts, #Fantasy Fiction; Swedish

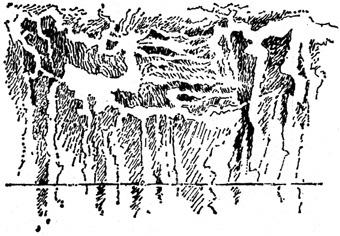

That's it, Toft whispered. Now anybody can attack him, he's not electric any more... he's just shrinking and shrinking and doesn't know where to turn... Toft curled up in the roach-net and started to describe it all for himself. He let the creature come to a valley where a toft lived who could make electric storms. The long valley was lit up by violet and white flashes, in the distance at first, then nearer and nearer...

*

Not a single fish had got caught in Grandpa-Grumble's contraption. He was dozing on the bridge with his hat over his nose. Beside him Mymble lay on the mat she had taken from in front of the stove and looked down into the running water. The Hemulen was sitting next to the letter-box painting big letters on a piece of plywood. He was writing 'Moominvalley' in mahogany stain.

'Who's that for?' Mymble asked. 'If anyone has walked as far as this he knows that he's here.'

'No, it's not for other people,' the Hemulen explained, 'it's for us.'

'Why?' asked Mymble.

'I don't know,' the Hemulen answered in surprise. He painted the last letter while he was thinking and then suggested: 'Perhaps just to make sure? There's something rather special about names, if you see what I mean.'

'No,' said Mymble.

The Hemulen took a large nail out of his pocket and began to nail the plywood to the parapet of the bridge. Grandpa-Grumble roused himself and muttered: 'Save the Ancestor...' And Snufkin came out of his tent and shouted: 'What are you doing? Stop at once!'

They had never seen Snufkin lose his self-control before, it scared and embarrassed them. Nobody looked at him. The Hemulen took the nail out.

'There's no need to feel hurt!' Snufkin called out petulantly. 'You know what I'm like!'

Even a hemulen should learn that a snufkin loathes notices, everything that reminds him of private property, No entry, Off limits, Keep out - if one is the least bit interested in a snufkin one knows that notices are the only things that can make him angry, vulnerable and at the mercy of others. And now he felt ashamed! He had shouted and carried on and it was not to be forgiven, even if one took out all the nails in the world!

The Hemulen let the piece of plywood slide down into the river. The letters quickly darkened and became unreadable and the notice was carried away by the current down to the sea.

'Look,' the Hemulen said, 'there it goes. Perhaps it wasn't as important as I imagined.'

The Hemulen's voice had changed just a little. There was a little less respect in it, he had come closer to someone, and he had a right to. Snufkin didn't say anything, but stood quite still. Suddenly he ran up to the letter-box by the parapet, lifted the lid and looked inside, then ran on to the maple-tree and shoved his arm in a hole in the trunk.

Grandpa-Grumble stood up and shouted: 'Are you expecting a letter?'

Snufkin had reached the woodshed. He turned the chopping-block upside down. He went inside the woodshed and searched behind the little window-shelf above the carpenter's bench.

'Are you looking for your glasses?' asked Grandpa-Grumble with interest.

Snufkin walked on. He said: 'I want to look in peace.'

'Do you really!' exclaimed Grandpa-Grumble and followed as fast as he could. 'You're quite right. There was a time when I used to search for things and words and names the whole day long and the worst thing was when other people tried to help.' He grabbed Snufkin's coat and held on tight and said: 'Do you know what it was like all day? Like this: when did you see it last? Try and remember. When did it happen? Where did it happen? Ha ha, all that's over and done with. I'll forget what I like and lose just what I like. Now, I can tell you...

'Grandpa-Grumble,' said Snufkin, 'the fish swim along the bank in the autumn. There aren't any fish in the middle of the river.'

'The brook,' corrected Grandpa-Grumble cheerfully. 'That was the first sensible thing I've heard today.' He went off immediately. Snufkin went on with his search. He was hunting for Moomintroll's good-bye letter, which had to be somewhere because a moomintroll never forgets to say good-bye. But all their hiding-places were empty.

Moomintroll was the only one who knew how to write to a snufkin. Brief and to the point. Nothing about promises and longings and sad things. And a joke to finish up with.

Snufkin went into the house and up to the second floor. He forced out the big knot in the banisters and that was empty, too.

'Empty!' said Fillyjonk behind him. 'If you're hunting for their valuables they're not in there. They're in the clothes-cupboard and it's locked.' She sat in the doorway of her room with blankets round her legs and her feather-boa right up round her nose.

'They never lock anything,' said Snufkin.

'It's cold!' Fillyjonk cried. 'Why don't you like me? Why can't you find something for me to do?'

'You could go down into the kitchen,' Snufkin muttered, 'it's warmer there.'

Fillyjonk didn't answer. A very faint rumble of thunder could be heard in the distance.

'They never lock anything,' Snufkin said again. He went over to the clothes-cupboard and opened the door. The cupboard was empty. He went downstairs without looking behind him.

Fillyjonk got up slowly. She could see that the cupboard was empty. But out of the dusty darkness came a ghastly, Strange smell - it was the suffocating sweet smell of decay. Inside the cupboard there was nothing except a moth-eaten kettle-holder made of wool, and a soft layer of grey dust. Fillyjonk put her head inside, shivering as she did so. Weren't those straggly little footmarks in the dust, quite tiny ones, almost invisible...? Something had been living in the cupboard and had been let out. The kind of thing that crawls out when you turn a stone over, that crawls under rotting plants, she knew, and now they were loose! They had come out with scratching legs, with rattling backs and fumbling feelers or crawling on soft white stomachs... She screamed: 'Toft! Come here!' And Toft came out of the box-room, he was all crumpled up and confused and looked at her as though he didn't recognize her. He opened his nostrils, there was a very strong smell of electricity here, keen and pungent.

'They've got out!' Fillyjonk shouted. 'They have been living in there and now they've got out!'

The door of the clothes-cupboard swung open and Fillyjonk saw a movement, a glimpse of danger - she screamed! But it was only the mirror on the inside of the door. The cupboard was still empty. Toft came closer with his paws over his mouth, his eyes were round and jet black. The smell of electricity got stronger and stronger.

'I let it out,' he whispered. 'It does exist, and now I've let it out.'

'What have you let out?' Fillyjonk asked anxiously.

Toft shook his head. 'I don't know,' he said.

'But you must have seen them,' said Fillyjonk. 'Think carefully. What did they look like?'

But Toft ran back to the box-room and shut himself in. His heart was pounding furiously. So it was really true. The Creature had come. It was in the valley. He opened the book at the right place and spelt out the words as fast as he could: 'According to what we have reason to suppose, its constitution gradually adapted itself to these new surroundings and the necessity to master them little by little formed the conditions under which survival seemed possible. This existence, which we dare only characterize as a pure assumption, an hypothesis, continued its obscure development for an indeterminable period without its behaviour pattern in any way aligning itself with the course of events which we are accustomed to construe as normal...'

But I don't understand a thing, Toft whispered. It's all words, words... If they don't hurry up, everything will go wrong! He slumped over the book with his paws clutching his hair and went on describing things to himself, desperately and in a disordered fashion, for he knew that the Creature was getting smaller and smaller the whole time and couldn't really fend for itself.

The thunderstorm was getting closer and closer! The lightning was coming from all directions! The electric sparks flew all over the place and the Creature sensed it - now! And it grew and grew... and now there was more lightning, white and violet! The Creature became bigger and bigger. It became so big that it almost didn't need any family...

Then Toft felt better. He lay on his back and looked up at the skylight, which was full of grey clouds. He could hear the thunder rumbling in the distance. It sounded just like the growling noise you make in your throat just before you get really angry.

*

Step by step Fillyjonk went down the stairs. She supposed that the ghastly little things had not crawled off in different directions. It was more likely that they were all huddled together, a coherent mass waiting in some murky, damp corner. There they sat, quite silently, in one of the hidden and rotting holes of autumn. But perhaps not! Perhaps they were under the beds, in the desk drawers, in one's own shoes - they might be anywhere!

It isn't fair, Fillyjonk thought. Nothing like this happens to anyone in my circle of acquaintances, only to me! She ran down to the tent with long, anxious strides and fumbled desperately with the closed flaps, whispering

hoarsely: 'Open up open up for me... it's me, Fillyjonk!'

She felt safer inside the tent, sank down on the sleeping-bag and put her arms round her knees. She said: 'They've got out. Someone let them out of the clothes-cupboard and they may be anywhere... millions of horrid insects sitting and waiting...'

'Has anybody else seen them?' Snufkin asked cautiously.

'Of course not,' Fillyjonk replied impatiently. 'It's

me

they're waiting for!'

Snufkin knocked out his pipe and tried to think of something to say. There was more thunder.

'Now don't start saying there's going to be a thunderstorm,' said Fillyjonk threateningly. 'And don't say that my insects have gone away or that they don't exist or that they're too small or too kind, for it won't help me one bit.'

Snufkin looked straight at her and said: 'There's one place where they'll never come. The kitchen. They never come into the kitchen.'

'Are you absolutely sure?' asked Fillyjonk sternly.

'I'm convinced of it,' answered Snufkin.

There was another peal of thunder, this time quite close. He looked at Fillyjonk and grinned. 'There's going to be a thunderstorm anyway,' he said.

There really was a big storm coming in from the sea. The lightning was white and violet, he had never seen so many or such beautiful flashes of lightning at one time. A sudden pall had descended on the valley. Fillyjonk lifted up her skirts and rushed back through the garden with leaps and bounds and shut the kitchen door behind her.

Snufkin sniffed the air, it felt as cold as steel. It smelt of electricity. The lightning was pouring down in great quivering streaks, parallel pillars of light, and the whole valley was lit up by their blinding flashes! Snufkin jumped up and