Moominvalley in November (17 page)

Read Moominvalley in November Online

Authors: Tove Jansson

Tags: #General, #Fantasy, #Action & Adventure, #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Family, #Classics, #Children's Stories; Swedish, #Friendship, #Seasons, #Concepts, #Fantasy Fiction; Swedish

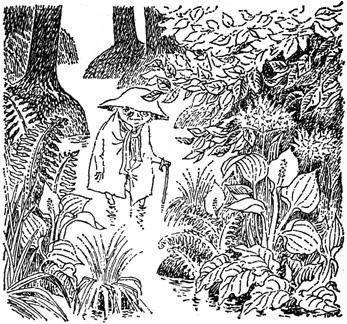

Snufkin went into the kitchen looking for his mouth-organ.

'It's on the shelf above the stove,' said Fillyjonk as she went past. 'I have been very careful with it.'

'You can keep it a little longer if you want,' said Snufkin uncertainly.

Fillyjonk answered in a matter-of-fact way: 'Take it. I'll get one of my own. And watch out, you're treading in the sweepings.'

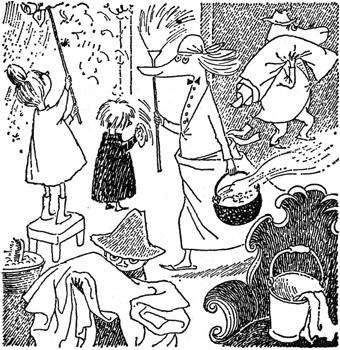

It was wonderful to be cleaning again. She knew exactly where the dust had hidden itself; soft and grey and self-satisfied it had made itself comfortable in the corners; she searched out every single bit of fluff which had rolled itself into big fat balls full of hairs and thought it was safe, ha ha! Moth-larvae, spiders, centipedes, all kinds of creepy-crawlies were routed out by Fillyjonk's big broom, and lovely streams of hot water and soapy lather washed everything away, and it was by no means an inconsiderable amount of mess that went out of the door, bucketful after bucketful; it was really fun to be alive!

'I've never liked it when the womenfolk clean up,' said Grandpa-Grumble. 'Has anyone told her not to touch the Ancestor's clothes-cupboard?'

But the clothes-cupboard was cleaned, too, it had twice as big a cleaning as all the rest. The only thing that Fillyjonk didn't touch was the mirror inside the cupboard, she let that stay misty.

After a while, the fun of cleaning became contagious, and everybody except Grandpa-Grumble joined in. They carried water and shook carpets, they scrubbed a bit of floor here and there, they each had a window to clean and when they felt hungry they went into the pantry and looked for what was left over from the party. Fillyjonk didn't eat anything and she didn't talk, how on earth should she have time or inclination for things like that! Sometimes she whistled a little, she was light on her feet and moved like the wind - one moment here another there, she made up

for all her desolation and fright and thought casually: whatever took possession of me? I have been nothing better than a great big ball of fluff... and why? But she couldn't remember.

And so the wonderful day of the great cleaning came to a close, and, thank goodness, without rain. When dusk came everything was straight again, everything was clean, polished, aired and the house stared in surprise in all directions through its freshly-cleaned windows. Fillyjonk took off her scarf and hung Moominmamma's apron on its Peg.

'That's that,' she said. 'And now I'm going home to clean my own place. It needs it.'

They sat on the veranda steps together, it was very cold in the evenings now, but a feeling of approaching change and departure kept them sitting there.

'Thanks for cleaning the house,' said the Hemulen in a voice filled with sincere admiration.

'Don't thank me,' Fillyjonk answered. 'I couldn't stop myself! You ought to do the same. Mymble, I mean.'

'There's one thing that's funny,' said the Hemulen. 'Sometimes I feel that everything we say and do and everything

that happens has happened once before, eh? If you understand what I mean. Everything is the same.'

'And why should it be different?' Mymble asked. 'A hemulen is always a hemulen and the same things happen to him all the time. With mymbles it sometimes happens that they run away in order to get out of the cleaning!' She laughed loudly and slapped her knees.

'Will you always be the same?' Fillyjonk asked her out of curiosity.

'I certainly hope so!' Mymble answered.

Grandpa-Grumble looked from one to the other, he was very tired of their cleaning and their talk about things which didn't make anything seem more real. 'It's cold here,' he said. He got up stiffly and went into the house.

'It's going to snow,' Snufkin said.

*

It snowed for the first time the next morning, small, hard flakes, and it was horribly cold. Fillyjonk and Mymble stood on the bridge and said good-bye. Grandpa-Grumble had still not yet woken up.

*

'This has been a very rewarding time,' said the Hemulen. 'I hope we shall meet again with the family.'

'Yes, yes,' said Fillyjonk absently. 'In any case, say that the china vase is from me. What's the name of that mouth-organ?'

'Harmonium Two,' said Snufkin.

'Have a nice journey,' Toft mumbled. And Mymble said: 'Give Grandpa-Grumble a kiss on the nose from me. And remember that he likes gherkins and that the river is a brook!'

Fillyjonk picked up her suitcase. 'See that he takes his medicine,' she said severely. 'Whether he wants to or not. A hundred years aren't to be taken lightly. And you can have a party now and then if you want.' She went on across the bridge without turning round. They disappeared in the swirling snow, lost in that mixed feeling of melancholy and relief that usually accompanies good-byes.

*

It snowed all day and got even colder. The snow-covered ground, the departure, the clean house - all gave the day a feeling of immobility and reflection. The Hemulen stood looking up at his tree, sawed off a bit of plank but let it lie on the ground. Then he stood and just looked. Sometimes he went and tapped the barometer.

Grandpa-Grumble lay on the drawing-room sofa and meditated upon the way things had changed. Mymble was right. Quite suddenly he had discovered that the brook was a stream, a brown stream curving past snowy banks and quite simply a brown stream. Now there was no point in fishing any longer. He put the velvet cushion over his head and recalled his own happy brook, he remembered more and more about it, and how the days passed long, long ago when there were lots of fish and nights were warm and light, and things happened all the time. One ran oneself off one's legs so as not to miss anything that happened, sometimes taking a little nap as an afterthought, and laughing at everything... He went to talk to the Ancestor. 'Hallo,' he said. 'It's snowing. Why do only little things happen nowadays? Why are they so trivial? Where is my brook?' Grandpa-Grumble was silent. He was tired of talking to a friend who never answered. 'You are too old,' he said, and thumped on the floor with his stick. 'And now that the

winter has come you'll get even older. One gets terribly old in the winter.' Grandpa-Grumble looked at his friend and waited. All the doors were open and the rooms were bare and clean, all the cheerful sloppiness had gone, the carpets lay fair and square in their rectangles, and it was cold and the snowy winter light fell on everything, Grandpa-Grumble suddenly felt angry and forlorn and shouted: 'What? Say something!' But the Ancestor didn't answer, but stood there gaping in his dressing-gown, which was too long for him, and didn't say a word.

'Come out of your cupboard,' said Grandpa-Grumble sharply. 'Come out and have a look. They've changed everything and we're the only two who know what things were like at the beginning.' Then Grandpa-Grumble poked the Ancestor in the stomach with his stick rather violently. There was a tinkling sound and the old mirror fell apart and crashed to the floor, a single long narrow splinter pausing momentarily on the Ancestor's bewildered face - and it fell, too, and Grandpa-Grumble stood face to face with a sheet of brown cardboard that meant absolutely nothing to him.

'Oh, indeed, it's like that is it?' said Grandpa-Grumble. 'He's gone. He got angry and left.'

*

Grandpa-Grumble sat in front of the kitchen stove thinking. The Hemulen was sitting at the table with a lot of drawings spread out in front of him. 'Something's not right about the walls,' he said. 'They're crooked in the wrong way and you just fall through them. It's absolutely impossible to get them to fit the branches.'

Perhaps he went into hibernation, Grandpa-Grumble thought.

'As a matter of fact,' the Hemulen went on, 'walls just shut one in. If you sit in a tree perhaps it's nicer after all to see what's going on around you, what?'

Perhaps the important things happen in the spring, Grandpa-Grumble said to himself.

'What do you think?' the Hemulen asked. '

Is

it nicer?'

'No,' Grandpa-Grumble said. He hadn't been listening. At last he knew what he would do, it was quite simple! He would skip over the whole winter and with a single leap find himself in April. There was nothing worth bothering about, absolutely nothing! All he had to do was make a nice hole to sleep in for himself and let the world go by. When he woke up again everything would be as it should be. Grandpa-Grumble went into the pantry and took down the bowl with the spruce-needles, he was very happy and suddenly terribly sleepy. He walked past the brooding Hemulen and said: 'Bye-bye, I'm going to hibernate.'

*

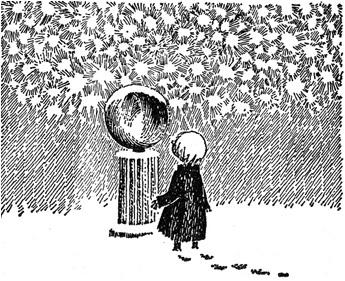

That night the sky was completely clear. The thin ice crunched beneath Toft's paws as he walked through the garden. The valley was full of the silence of the cold and the snow shone on the hill slopes. The crystal ball was empty. It was nothing more than a pretty crystal ball. But the black sky was full of stars, millions of sparkling glittering diamonds, winter stars shimmering with the cold.

'It's winter now,' said Toft as he came into the kitchen.

The Hemulen had decided that the house would be nicer without walls, just a floor, and he bundled his papers together with a feeling of relief and said: 'Grandpa-Grumble has hibernated.'

'Has he got all his things with him?' Toft asked.

'What does he need them for?' the Hemulen said in surprise.

Of course, when you hibernate you're much younger when you wake up, and you don't need anything but to be left in peace. But Toft imagined that when one wakes up it's important to know that someone had thought about one while one has been sleeping. So he looked for Grandpa-Grumble's things and put them outside the clothes-cupboard. He covered Grandpa-Grumble with the eiderdown and tucked him up properly, the winter might be cold. The clothes-cupboard smelt faintly of spices. There was just enough brandy left for a refreshing thimbleful in April.