Moominvalley in November (12 page)

Read Moominvalley in November Online

Authors: Tove Jansson

Tags: #General, #Fantasy, #Action & Adventure, #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Family, #Classics, #Children's Stories; Swedish, #Friendship, #Seasons, #Concepts, #Fantasy Fiction; Swedish

CHAPTER 14

Looking for the Family

IT

was taken for granted that no one slept in Moominmamma's room or in Moominpappa's room. Because she was fond of the morning, Moominmamma's room faced east and Moominpappa's faced west because the evening sky used to make him feel wistful.

One day at dusk the Hemulen crept up to Moominpappa's room and stood respectfully in the doorway. It was quite a small room with a sloping ceiling, a place where one could be by oneself. Or a place where one could be got out of the way. On the blue walls Moominpappa had hung up curiously-shaped branches and he had stuck trouser-buttons on some of them. There was a calendar with a picture of a shipwreck and a piece of board saying Haig's Whisky hung over the bed. On the desk there were some peculiar stones, a nugget of gold and a mass of the sort of odds and ends one leaves behind at the last minute when one goes on a journey. Under the mirror there was a model of a lighthouse with a pointed roof, a little inlaid wooden door and a railing of brass nails round the lamp-room. There was even a ladder which Moominpappa had made out of copper wire. He had pasted silver paper on all the windows.

The Hemulen looked at all this and tried to remember what Moominpappa was like. He tried to remember the things they had done together and what they had talked about, but he couldn't. Then he went over to the window and looked out at the garden. The shells round the dead flower-beds shone in the twilight and in the west the sky was yellow. The big maple-tree was coal-black against the sunset - the Hemulen was looking at exactly what Moominpappa looked at in the autumn twilight.

Then all of a sudden the Hemulen knew what he would do, he would build a house for Moominpappa in the big maple-tree! He was so pleased with this idea that he started to laugh! A tree-house, of course! High above the ground between the strong black branches far away from the family, free and full of adventure and with a storm lantern on the roof; there they would sit and listen to the south-wester making the walls creak and talk to each other at last. The Hemulen rushed out into the hall and called: 'Toft!'

Toft came out of his box-room.

'Have you been reading again?' the Hemulen asked. 'It's dangerous to read too much. Listen, do you like pulling out nails, eh?'

'I don't think so,' answered Toft.

'If anything is going to get done,' the Hemulen explained, 'one person does the building and the other carries the planks. Or one knocks in new nails and the other one pulls out old nails. Do you understand?'

Toft just looked. He knew that he was the other one.

They went down to the woodshed and Toft began to pull out nails. They were old boards and planks which the Family had collected on the beach, the grey timber was hard and compact and the nails rusted in. The Hemulen went on to the maple-tree, and looked up thoughtfully.

Toft prised the nails loose and pulled. The sunset was a fiery yellow just before the sun went down. He told himself about the Creature, and he could do it better and better, not in words any longer but in pictures. Words are dangerous things and the Creature had reached a vital point in its development, it was just about to change. It didn't hide itself any longer, it watched and listened, it slid like a dark shadow towards the edge of the forest, very intently and not at all afraid...

'Do you like pulling out nails?' Mymble asked behind him. She was sitting on the chopping-block.

'What?' said Toft.

'You don't like pulling out nails, but you do it all the same,' said Mymble. 'I wonder why?'

Toft looked at her and kept quiet. Mymble smelt of peppermints.

'And you don't like the Hemulen either,' she went on.

'I've never given it a thought,' Toft muttered deprecatingly, and immediately started to think whether he liked the Hemulen or not.

Mymble jumped down from the chopping-block and went away. The twilight suddenly deepened and a grey mist rose over the river, it was very cold.

'Open up,' shouted Mymble outside the kitchen door. 'I want to warm myself in your kitchen.'

It was the first time anybody had said 'your kitchen' and Fillyjonk opened the door at once. 'You can sit on my bed, but mind you don't crumple the bedspread.'

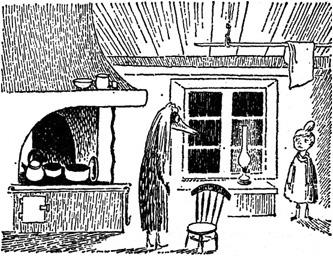

Mymble curled up on the bed which had been pushed between the stove and the sink and Fillyjonk went on

making the bread pudding for the next day. She had found a bag of old crusts that the family had been saving for the birds. It was warm in the kitchen, the fire crackled in the stove, throwing flickering shadows on the ceiling.

'Right now it's just like it always used to be,' said Mymble to herself.

'You mean like it was in Moominmamma's day,' said Fillyjonk to be precise but without thinking.

'No, not at all,' Mymble answered. 'Just the stove.'

Fillyjonk went on with the bread pudding, going backwards and forwards in the kitchen on her high heels, and her thoughts suddenly became anxious and uncertain. 'What do you mean?' she asked.

'Moominmamma used to whistle while she was cooking,' Mymble said. 'Everything was a little just anyhow... I don't know - it was different. Sometimes they took their food with them and went somewhere, and sometimes they didn't eat at all...'She put her arm over her head in order to go to sleep.

'I should imagine that I know Moominmamma considerably better than you do,' Fillyjonk said. She greased the baking-tin, threw in the last of the soup from the day before and surreptitiously added a few boiled potatoes which were no longer what they had once been; she got more and more agitated and in the end she dashed over to the sleeping Mymble and shouted: 'You wouldn't lie there sleeping if you knew what I know!'

Mymble woke up and lay still, looking at Fillyjonk.

'You've no idea,' whispered Fillyjonk intensely. 'You've no idea what has broken loose in this valley! Horrid things have been let out of the clothes-cupboard upstairs and they're everywhere!' Mymble sat up and asked: 'Is that why you've got fly-paper round your boots?' She yawned and rubbed her nose. She turned round in the doorway and said: 'Don't fuss, there's nothing here that's worse than we are ourselves.'

'Is she angry?' Grandpa-Grumble asked from the drawing-room.

'She's scared,' answered Mymble and went up the stairs. 'She's scared of something in the clothes-cupboard.'

It was now quite dark outside. They had all got used to going to bed when it got dark, and they slept for a long time, longer and longer as the days drew in. Toft crept in like a shadow and gave a mumbled good night and Hemulen turned his nose to the wall. He had decided to build a cupola on the top of Moominpappa's tree-house. He could paint it green and perhaps put gold stars on it. There was generally some gold paint in Moominmamma's desk and he had seen a tin of bronze paint in the woodshed.

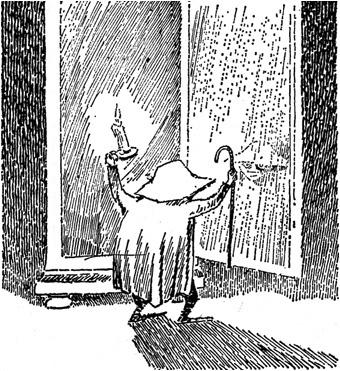

When they were all asleep, Grandpa-Grumble climbed

the stairs with a candle. He stopped outside the big clothes-cupboard and whispered: 'Are you there? I know you're there.' He opened the cupboard very gently, and the door with the mirror swung open.

The candle flame was very small and gave very little light in the hall, but Grandpa-Grumble could see the Ancestor quite clearly in front of him. He was wearing a hat and carried a stick and looked highly improbable. His dressing-gown was too long and he was wearing gaiters. But no glasses. Grandpa-Grumble took a step forward and the Ancestor did the same thing.

'So you don't live in the stove any longer,' said Grandpa-Grumble. 'How old are you? Don't you ever wear glasses?' He was very excited and thumped with his stick on the floor to give emphasis to what he was saying. The Ancestor did the same, but didn't answer.

He's deaf, said Grandpa-Grumble to himself. A stonedeaf old bag of bones. But in any case it's nice to meet someone who knows what it feels like to be old. He remained there staring at the Ancestor for a long time. The Ancestor did the same. They parted with feelings of mutual esteem.

CHAPTER 15

Nummulite

THE

days were growing shorter and colder. It didn't rain very often. The sun shone down into the valley for a short while each day and the bare trees threw shadows on the ground but in the morning and in the evening everything lay in half-light and then night came. They never saw the sun go down but they did see the yellow glow of the sunset in the sky and the sharp outlines of the mountains all round - it was like living in a well.

The Hemulen and Toft were building Moominpappa's tree-house. Grandpa-Grumble caught a couple of fish every day and Fillyjonk had begun to whistle.

It was an autumn without storms and the big thunderstorm didn't come back, but rolled past in the distance with a faint rumbling sound that made the silence in the valley seem even deeper. Only Toft knew that every time the thunder was heard the Creature grew and lost a bit more of its shyness. It was fairly big now and had changed a lot, it had opened its mouth and had shown its teeth. One evening in the yellow light of sunset the Creature leant over the water and saw its own white teeth for the first time. It opened its mouth and yawned, then snapped its mouth shut and gnashed its teeth a bit, and thought: I don't need anyone now, I've got teeth.